He is wrong. But give him some credit. Unlike most racial egalitarians, Sasha Gusev supports his ad hominem attacks on hereditarians with arguments. While many of those arguments are fallacious or empirically dubious, they are still arguments, and arguments, unlike insults or moral denunciations, can be refuted.

In a recent example, Gusev reproved “racism Twitter” for asserting that observed racial differences in IQ and other traits are partially genetic in origin. He called this view “aggressively misleading” and claimed it was “completely unsupported by the data.” He then proceeded to offer several erroneous claims himself before advancing the implausible notion that education is the primary cause of the enduring Black–White IQ gap.

Here I respond, arguing that education, like the innumerable other environmental hypotheses proposed over the past sixty years, cannot account for the gap. Judged on weight of evidence, the environment-only theory of race differences is a spectacular failure, sustained largely by moral intimidation and other extra-scientific pressures. To be sure, hereditarianism may yet turn out to be false, but at present the cause of the IQ gap sure looks genetic. And there is little doubt that the unpopularity of hereditarianism among elites owes more to its incendiary implications than to its scientific shortcomings.

I begin with a brief summary of the topic of race differences in intelligence before moving to a more detailed refutation of Gusev’s arguments.

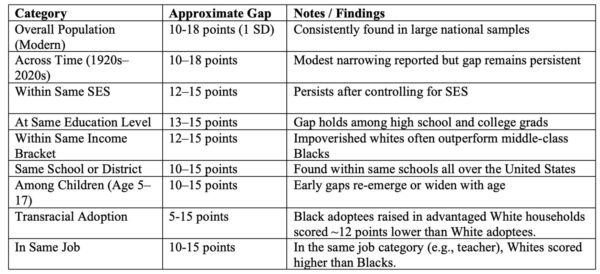

In the United States, Blacks score substantially lower than Whites on tests of cognitive ability. The size of this gap varies somewhat across time and region, but not by much. Indeed, one might venture a “law” of Black–White IQ differences: in nearly every subgroup examined, a gap of roughly one standard deviation between Blacks and Whites will appear. Like other sociological generalizations, this law is more flexible and less precise than those found in physics or chemistry. Yet it remains a surprisingly accurate starting assumption whose utility poses a serious challenge to environment-only hypotheses.

Since the discovery of the Black–White IQ gap, theorists have debated its causes. These debates gave rise to two broad research traditions: the environment-only theory and hereditarianism. The environment-only theory holds that racial differences in cognitive ability are almost entirely the product of environmental variation, whether physical, social, or cultural.

Hereditarianism, by contrast, maintains that such differences likely arise from the same forces that explain individual variation, namely, some combination of genetic and environmental influences. One can thus imagine environmentalism and hereditarianism as a practical dichotomy created from a continuum of belief about the importance of the genetic contribution to racial differences, ranging from 0% to 100%. Hereditarians think genes contribute, say, 20% or more of the gap, whereas environmental-only theorists think genes contribute less than 20%.

Although various scholars and intellectuals, including Thomas Jefferson, had long speculated that Whites might possess innately higher cognitive abilities than Blacks, the hereditarian position did not take on a distinctly scientific form until the 1960s, perhaps most notably with the publication of Arthur Jensen’s soon-notorious article How Much Can We Boost IQ and Scholastic Achievement?

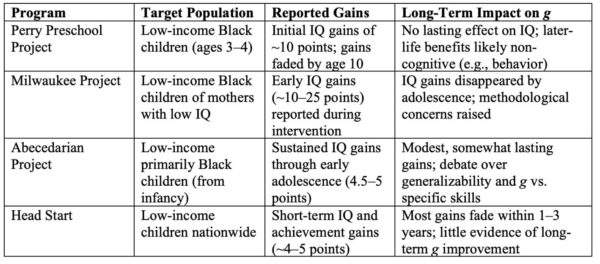

In that article, Jensen advanced several arguments that remain central to debates between hereditarians and environmentalists today: 1) IQ is a highly heritable trait; 2) The IQ gap between Black and White Americans is large and persistent; 3) Socioeconomic status and educational factors do not adequately explain this gap; 4) Compensatory education programs have largely failed to produce enduring gains in IQ; 5) The hypothesis that genetic factors contribute to the Black–White IQ gap is scientifically plausible and should not be dismissed out of hand.

About boosting intelligence, Jensen concluded:

The techniques for raising intelligence per se, in the sense of g, probably lie more in the province of the biological sciences than in psychology and education.

After over fifty years of research and copious failed attempts to increase g, this assertion has been confirmed. If there is an environmental mechanism for boosting intelligence (in the sense of g), it has not been found despite massive expenditures of time, money, and energy.

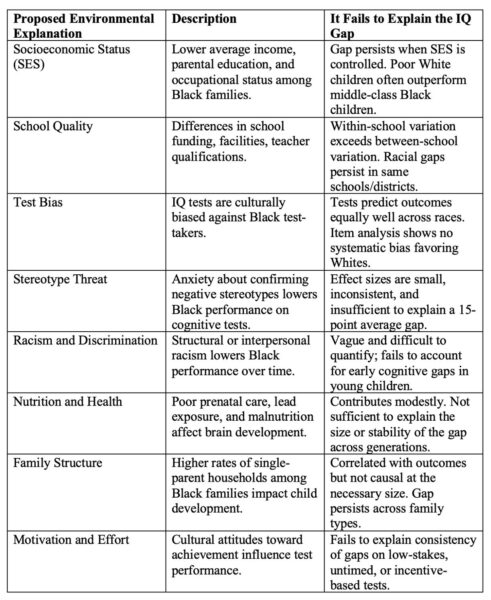

Thus, it is not for lack of trying that environment-only theories have failed. Theorists have proposed a wide range of environmental and cultural explanations for the Black–White IQ gap. Some of these originally seemed plausible, such as prenatal nutrition or impoverished verbal environments; others, like stereotype threat or caste status, bordered on the ludicrous. To date, none of these hypotheses has withstood serious empirical scrutiny. Taken together, contemporary environmental and cultural accounts are underwhelming, explaining at best only a small fraction of the gap—if they explain it at all.

Consider perhaps the most obvious explanation: socioeconomic status (SES). Many people, upon first encountering evidence of a large IQ gap between Black and White Americans, respond intuitively: “Well, of course! Black families are poorer and less educated. Once that gap closes, so too will the IQ gap.”

But scholars have long understood that parental SES cannot account for the IQ gap, and is likely to have limited causal influence on IQ within the normal range of environmental variation. As Richard Haier and colleagues wrote in their textbook on intelligence:

Family environments may contribute to children’s development of intelligence, but, within the range of normal family environments in more middle- and high-income nations, these effects appear to be modest and ephemeral.

When considering SES, it is crucial not to confuse correlation with causation. Although there is a well-documented statistical association between parental SES and children’s IQ, much of this relationship is likely driven by genetics. The same genes that contribute to higher cognitive ability in adults, enabling them to achieve greater socioeconomic success, are passed on to their children, influencing the children’s intelligence. In other words, smart parents tend to attain higher SES and have smart children largely because of genes, not because of environmental advantages.

As a result, studies that control for SES (and other correlated variables) when comparing Black and White IQ scores tend to be overly generous to the environment-only position. The common inference that any diminution in the IQ gap after such controls must reflect environmental causation is an example of the sociologist’s fallacy.

Even so, controlling for a wide range of variables related to education and economic status does not eliminate the Black–White IQ gap, and often leaves 50 to 70 percent of it intact. In fact, Black children born to high-status parents frequently score lower on standardized tests (and other measures of cognitive ability) than White children born to middle-status or even low-status parents. For example, the poorest White SAT takers often score as high as the wealthiest Black SAT takers. Similar results abound in the literature.

When comparing high-SES Blacks and Whites, the IQ gap is generally a standard deviation or larger. As Noah Carl noted in Aporia:

There are several datasets, such as the NLSY (see p. 288) and Project Talent, where the gap is just as large in the top decile of parental SES as it is in the population as a whole. This means that when you have black and white Americans, all of whom were raised in wealthy families living in affluent neighbourhoods with access to good schools, the whites score about one standard deviation higher on IQ tests.

The same holds for parental education. As Meng Hu noted in a recent publication:

Another finding of interest is that both Asian and White students with poorly educated parents (high school only or no high school) often achieve higher SAT scores than Black students with highly educated parents (advanced degree or doctoral degree).

While environment-only hypotheses have routinely been falsified or at least deflated and rendered dubious, the evidence for the genetic hypothesis has continued to accumulate. Many lines of argument now support it, including high within-group heritability, transracial adoption studies, persistence of the differences, Spearman’s hypothesis, tests of measurement invariance, admixture studies, different proportions of target alleles in mental abilities, and MRI studies.

Perhaps the most direct empirical support for hereditarianism comes from admixture studies, and so it is worth addressing these briefly. Admixture studies examine populations with varying degrees of ancestry from different racial or ethnic groups, relating the proportion of genetic admixture to outcomes such as intelligence. The underlying assumption is straightforward: if genetic differences contribute to group differences in IQ, then individuals with a higher proportion of ancestry from a group with higher average IQ should, on average, score higher than those with less of that ancestry.

In the United States, both Black and Hispanic populations are genetically admixed. On average, Hispanics possess approximately 55–70% European ancestry, while Black Americans typically have 15–25% European admixture. Given that populations of European descent tend to score higher on IQ tests than populations of African or Native American descent, the hereditarian hypothesis predicts that individuals with higher proportions of European ancestry should, on average, exhibit higher cognitive ability as measured by standardized intelligence tests.

The strongest admixture studies have found the predicted relation between European ancestry and cognitive ability, with correlations ranging from r = .23 to .30. Of course, these studies have limitations and are by no means dispositive. Nevertheless, their findings should reasonably update the priors of any honest scholar and serve as a basis for further, more rigorous research. And they demonstrate the fruitfulness of the hereditarian research tradition, which continues to forward and confirm hypotheses, unlike the environment-only tradition, which has almost completely stalled.

Indeed, since at least the 1980s, environment-only theorists have resembled a once overconfident army in constant retreat, abandoning one proposed explanation after another, each initially embraced with enthusiasm, only to be vanquished by empirical reality. Today, few environment-only theorists even attempt to engage hereditarianism directly; and when they do, the vehemence of their objections often rivals the flimsiness of their arguments. To them, hereditarianism is not a scientific hypothesis but an apology for racism.

Sasha Gusev’s recent posts exemplify both tendencies. After deriding “racism Twitter” for promoting the “aggressively misleading” claim that genes likely play a role in racial differences in cognitive ability, Gusev asserted that “genetic difference between any two populations can go either direction” and argued that gene–environment interactions “make the notion of ‘explaining’ differences intractable”.

As far as I can tell, the claim here is something like:

Yes, there is a 15-point IQ gap between Blacks and Whites in the United States. But we do not have any idea what direction the genetic differences go. Maybe Blacks have a genetic advantage over whites. We just don’t know.

As anyone engaged in rational inquiry understands, it is essential to distinguish the merely possible from the plausible or likely. It is possible, for instance, that a lucky amateur could defeat Magnus Carlsen in a game of chess, but repeatedly betting on such an outcome is a good way to go broke. Similarly, it is possible that the genetic differences between any two populations can “go in either direction.” One can imagine it and it is not logically incoherent. But in many cases it is wildly implausible.

There is virtually no credible chance that Black populations are genetically more intelligent than White populations, just as there is virtually no credible chance that Golden Retrievers are genetically more aggressive than Pit Bulls. The direction of observed differences is not arbitrary and is informative about underlying genetic differences, especially when the populations in question inhabit substantially overlapping environments.

Gusev then claimed, “The mere fact that a trait is heritable within populations tells us nothing about the explanatory factors between populations.” But this is rhetorical sleight of hand, a fallacious leap from not dispositive to tells us nothing. Consider an analogous statement:

The mere fact that a city is located in Florida tells us nothing about its temperature in July compared to a city in Michigan.

The obvious response is that of course it does. Cities in Florida are generally hotter than cities in Michigan, even if not always. Therefore, knowing a city’s location tells us something about its likely temperature just as knowing that a trait is highly heritable within populations tells us something about the likely causes of differences between them, especially if they inhabit overlapping environments. Heritability within groups may not settle the question of group differences, but it surely informs it.

It is telling that the two examples Gusev forwarded to illustrate his claim that heritability within-groups “tells us nothing” about group differences are highly artificial and ill-suited to the case of Blacks and Whites in the United States. The first is the now-famous “corn seed” analogy forwarded by Richard Lewontin in which seeds are planted in two trays of vermiculite and watered with different nutrient solutions, one normal and one deficient in nitrates and lacking zinc. Unsurprisingly, the corn in the deficient tray is substantially shorter. Within each tray, the variation in height is almost entirely genetically caused, but between the trays, the variation is entirely environmental. The lesson, according to Lewontin: large group differences can be wholly environmental even when within-group heritability is high.

But while the logic holds within this narrowly controlled and contrived setup, the analogy breaks down when applied to human populations who do not inhabit such sharply divergent environments. Indeed, the environments of Black and White Americans overlap extensively, making the Lewontin scenario a poor model for real-world inference.

The second is an even more fantastical example from Freddie DeBoer in which children are either fitted with weighted belts or springy shoes and asked to participate in a jumping contest. Of course, we find that the children with weights do not jump so high as the children with springy shoes. Within each group of children, much of the variation in jumping is caused by differences in genes. But between groups, the variation is caused by the environment (i.e., the weights and the shoes).

Like the corn-seed example, this is a fantasy that has little relevance for the Black-White IQ gap. Contra DeBoer and Gusev, the reality in the contemporary United States is not one in which Blacks have been crushed by state-sanctioned burdens while Whites have been elevated by privilege.

On the contrary, elites in the United States have worked assiduously to raise Black performance, not to suppress it. They have spent hundreds of billions of dollars trying to close the race gap. They have discriminated against Whites and Asians in college admissions and on the job market. They have castigated Whites for talking honestly about group differences. They have promulgated bizarre theories of systemic racism and elevated Black mediocrities to positions of undeserved prominence. And yet, the IQ gap remains, impressively stable and apparently impervious to environmental intervention.

After reiterating the view that group differences might go in either direction, Gusev favorably cited David Reich’s contention in Who We Are and How We Got Here that race realists who expect “genetic differences to line up with long-standing stereotypes” are “peddling racist pseudoscience.” Here is Reich’s passage castigating James Watson, Nicholas Wade, and Henry Harpending for their supposed racism:

If we can be confident of anything, it is that whatever differences [among human populations] we think we perceive, our expectations are most likely wrong. What makes Watson’s and Wade’s and Harpending’s statements racist is the way they jump from the observation that the academic community is denying the possibility of differences that are plausible, to a claim with no scientific evidence that they know what those differences are and also that the differences correspond to long-standing popular stereotypes—a conviction that is essentially guaranteed to be wrong.

I’m surprised that Gusev cited this passage approvingly because it is rather confused and self-contradictory. To unpack it, Reich contends that:

- Human populations are likely to differ psychologically partially because of genes.

- We have no idea what those differences will look like, and it is racist to claim otherwise with confidence.

- We can be nearly certain that the differences will not resemble popular stereotypes or current group differences.

But the third claim contradicts the second. If it is “racist” to assert any specific group-level differences with confidence, then why is it not also racist to assert with confidence that the differences will contradict popular expectations? After all, to negate a stereotype is to assert its opposite. If the stereotype is that Group A is taller than Group B, denying it implies that either Group B is taller than Group A, or that the groups are equal. Either way, a specific claim about group traits is being made. Reich’s logic ends up collapsing into a performative contradiction. He denounces certainty while expressing it.

What’s more, as I argued above, the notion that genetic differences will contradict most current phenotypic differences is deeply implausible. Imagine applying Reich’s logic to dogs. Suppose someone wrote the following:

I suspect we will discover genetically caused differences between dog breeds. However, what makes the average breeder’s beliefs problematic is that they assume these differences will reflect long-standing breed stereotypes. That assumption is almost certainly false. In truth, we have no idea what breed differences we’ll find. Perhaps Golden Retrievers are more aggressive than Rottweilers. Perhaps not. Who knows?

Would we take this seriously? Of course not. No reasonable person would deny that many popular beliefs about breed differences, though perhaps exaggerated, rest on broad, observable propensities which are partially caused by genes.

Since progressives do not hold sacred values about dogs, they can see the absurdity of this example. However, they do hold sacred values about human groups. And so they pretend we are utterly ignorant about the likely nature of racial variation and embrace the risible view that underlying genetic differences may in fact be the opposite of pervasive and persistent phenotypic differences.

Gusev believes, as far as I can tell, that the Black-White IQ gap is entirely environmental, pointing to education as a promising explanatory variable. But although education is undoubtedly important for developing various cognitive skills and even possibly for slightly boosting intelligence, it is almost certainly not the cause of the IQ gap.

First, it is implausible on its face since one finds a large Black-White IQ gap within almost every relevant school district across the United States:

In other words, there is no school district in the United States that serves a moderately large number of black or Hispanic students in which achievement is even moderately high and achievement gaps are near zero.

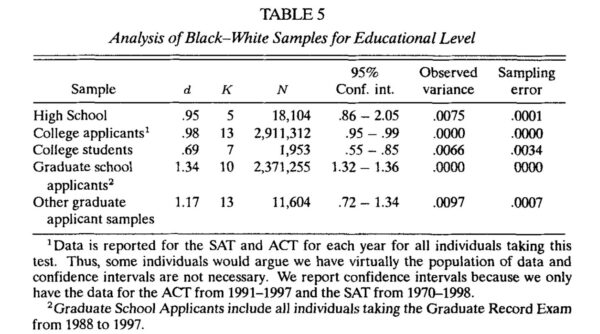

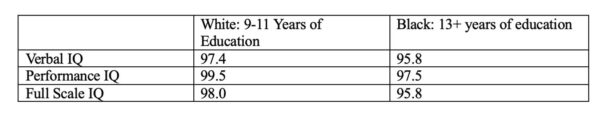

The Black-White IQ gap shows up early in life and is similar across all levels of education.

(Cohen’s d expresses the difference between group means in standard deviation units. A d of 0.95 means that, on average, Whites scored 0.95 standard deviations higher than Blacks. The column labeled K refers to the number of separate samples included in each category. K = 5 means that the data for that row were drawn from five distinct Black-White samples.)

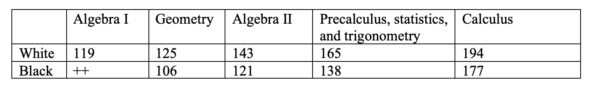

What is more, Whites often outperform Blacks on tests of cognitive ability even when the Blacks have had several years more formal education.

The same is true when comparing family education. As Jay M noted in a thorough piece on the pervasiveness of the Black-White IQ gap:

Controlling for parental education does not succeed in explaining the test score gap between blacks and whites. In fact, the average NAEP mathematics score of black students with parents who graduated from college was equal to the average score of white students with parents who did not finish high school (both groups score 138 points). The exact same pattern is found for reading scores (both groups score 274 points).

This should not be surprising since relevant experts now recognize that the effects of schooling have been exaggerated in the popular literature:

I further argue that the majority of the variance in educational outcomes is associated with students, probably as much as 90% in developed economies. A substantial portion of this 90%, somewhere between 50% and 80% is due to differences in general cognitive ability or intelligence. Most importantly, as long as educational research fails to focus on students’ characteristics we will never understand education or be able to improve it.

As Haier and colleagues put it their textbook on intelligence:

Among intelligence researchers, there is an emerging consensus that schools and teachers do not have as much effect on the development of intelligence as might be expected.

Furthermore, whereas the Black–White IQ gap primarily reflects differences in g, the gains from education tend to affect specific abilities and are largely unrelated to g:

These findings indicate that education’s ability to raise intelligence test scores is driven by domain-specific effects that do not show “far transfer” to general cognitive ability.

Put differently, education may be similar to practicing the piano or guitar. With effort, you improve your performance on that instrument, but you are unlikely to enhance your general musical aptitude. Just as no amount of practice will transform a musical mediocrity into Mozart, no amount of schooling will turn an average student into an Einstein.

To maintain that education is the primary cause of the Black–White IQ gap, one would have to accept a highly implausible set of claims:

- That education can substantially increase g, contrary to decades of psychometric evidence showing that schooling has, at best, modest and largely non-g-loaded effects on cognitive ability.

- That Black and White students from the same socioeconomic backgrounds and school districts nevertheless receive dramatically different educational experiences, to an extent sufficient to explain the persistent one standard deviation gap.

- That Black children from affluent, highly educated families receive substantially worse educations than White children from middle- or even lower-class families, despite their relative advantage in household resources, expectations and access to schools.

The most judicious conclusion is that schooling, like other environmental variables, has a limited effect on general intelligence but can improve various cognitive skills. This is not trivial. But it does mean that education is an unlikely explanation for persistent Black-White IQ gaps.

Like Nietzsche’s madman announcing the death of God, hereditarians have announced the death of racial egalitarianism. But as in Nietzsche’s fable, hereditarians may have come too soon; the masses are not ready for the message. Thus the environment-only theory will likely limp on, already half-dead, waiting for some future coup de grâce. In the meantime, those who care about the truth can be honest with themselves and others. The environment-only theory has been tried, and it has failed.

The post Sasha Gusev Is Wrong appeared first on American Renaissance.

American Renaissance

R1

R1

T1

T1