This video is available on Rumble, Bitchute, Odysee, Telegram, and X.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is supposed to be one of the great achievements of the so-called “civil rights era.”

Like all anti-discrimination laws, it mutated and metastasized, and now it’s back in the news, thanks to the Supreme Court.

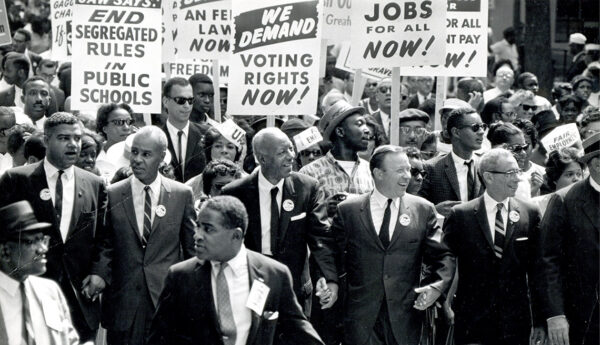

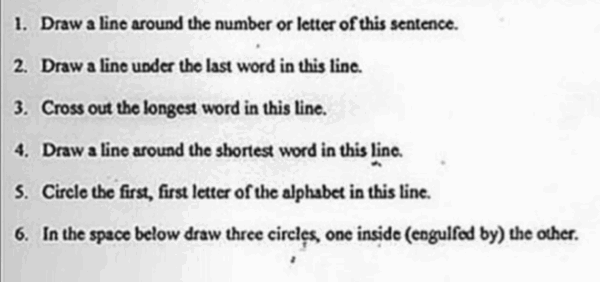

The law was supposed to ban practices that kept blacks from voting, such as literacy tests. Seven Southern states made people pass a test of reading or political knowledge before they could register to vote.

The tests were reportedly scored harshly against blacks, but they weeded out stupid whites, too.

I like literacy tests. I don’t want people voting if they can’t read English. However, as always seems to happen when racial differences are involved, the solution was not to score the tests fairly, but to eliminate them.

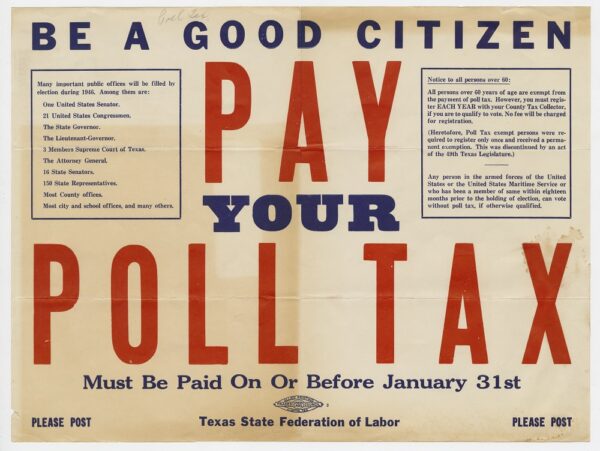

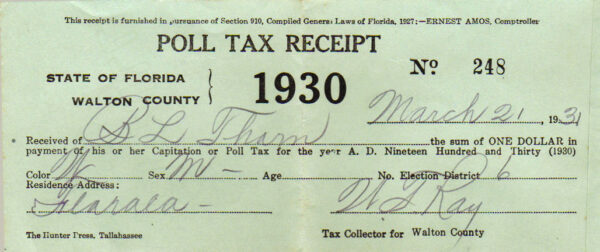

The other horrible racist trick was the poll tax.

Five Southern states charged an annual fee of $1.00 up to $2.00 to register. That would be $10 to $20 today.

I don’t think that’s bad, either. Keeps out bums and derelicts, not that many of them vote.

There were other parts of the Voting Rights Act, that came and went over the years, but the one that’s in the news now is the requirement — under most circumstances — to have majority non-white voting districts, if at all possible. If the lines of voting districts diluted the votes of non-whites and made it harder for them to elect people who looked like them, you had to draw new districts.

The 1986 US Supreme Court case Thornburg v. Gingles required racial gerrymandering if the following two conditions were met: First, there had to be enough BIPOCs to make up a majority in a “reasonably compact” district. Second, both whites and BIPOCs had to vote as blocs.

Credit Image: © Chuck Kennedy/TNS via ZUMA Press Wire

If 60 percent or more BIPOCs voted for a candidate — usually of their own race — and 60 percent or more whites voted for someone else, that was called racial polarization, which justified making a district that was majority BIPOC.

This became known as the Gingles framework, and many districts were redrawn to make non-whites the majority of voters.

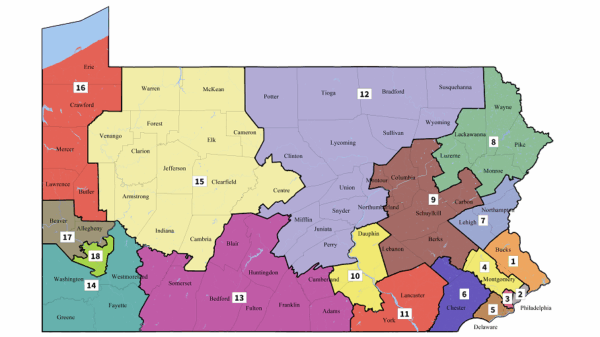

Each Congressional district has to have about 750,000 people. As you can see from this map of Pennsylvania, in the Philadelphia area, you can have small districts of 750,000 people, but in the countryside, you need to draw big districts to get that many people.

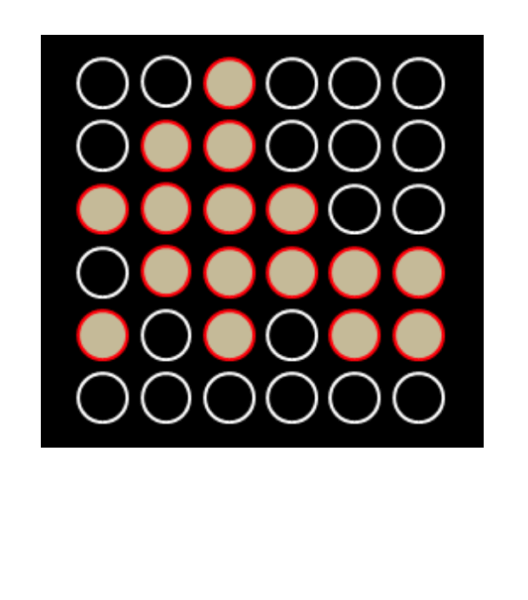

There are many ways to carve up districts for political reasons. Here’s a super simplified map with 36 voters. The tan circles are BIPOCs. There are 16 of them. There are 20 whites — the white circles — so whites are the majority.

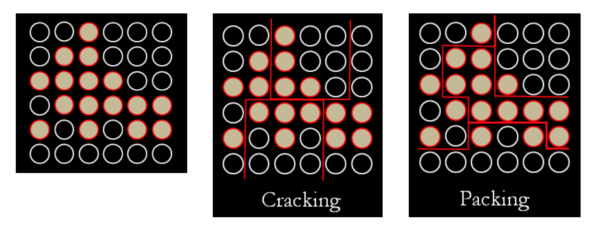

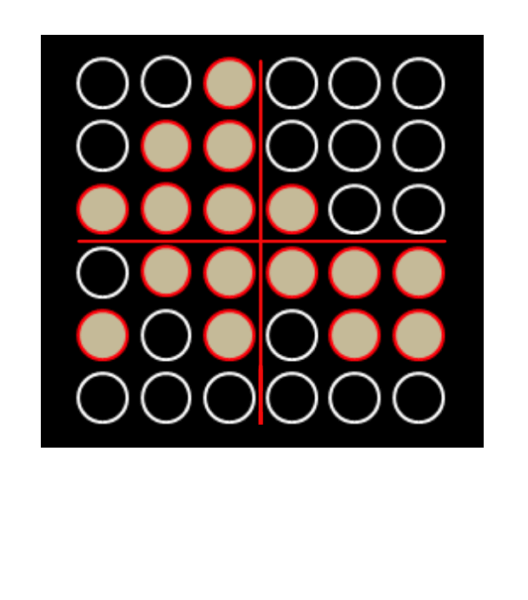

Let’s say you have to make four contiguous voter districts with nine people each, and before the Voting Rights Act, you wanted whites to outvote BIPOCs in all four. You did what is called cracking, and cleverly divided the BIPOCs up among the four districts so they are always outnumbered. In each district, it’s five whites to four BIPOCs.

Or, you can pack as many BIPOCs as possible into just one district and write it off as a loss. In two of the other three districts, you have comfortable white majorities and in the third, you have a five-four majority. Or, the Voting Rights Act would have required splitting the area into these four districts, with two minority-majority districts, one in the upper left and one in the lower right.

Republicans and Democrats are always trying to do the same thing along party lines to gain an advantage over each other.

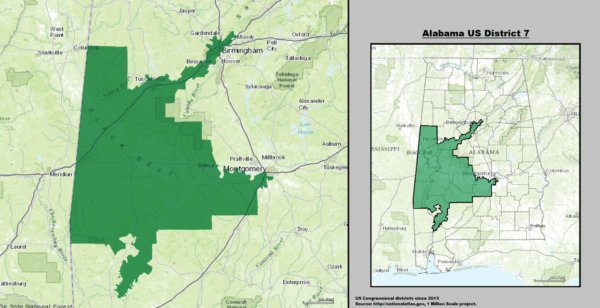

After the Supreme Court started requiring outright racial gerrymandering, we got some freakish results. Alabama’s Seventh District has these extensions added to it to draw in the black parts of Birmingham and Montgomery.

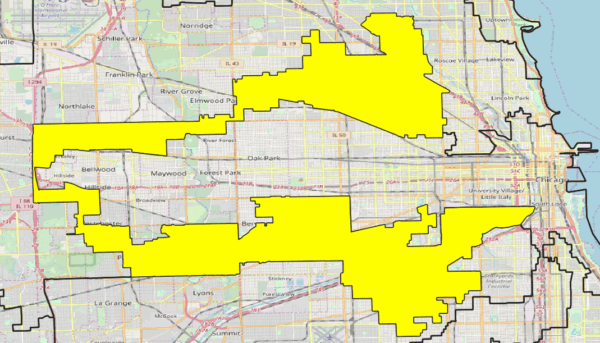

This district was drawn in 1992 to make it the first deliberately Hispanic-majority district.

The northern part is mostly Puerto Rican and the southern part is mostly Mexican, to make a district that was 65 percent Hispanic. The thin part on the left that joins the two parts is Interstate 294. No one lives there, but that makes the district “contiguous.” The area between the parts is in a deliberately black district.

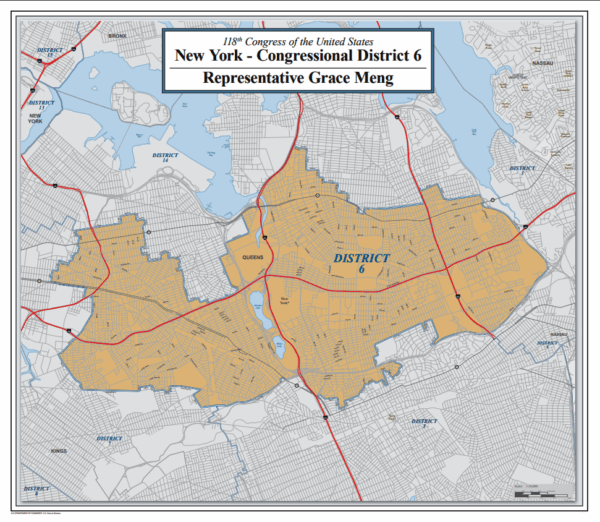

New York’s 6th district in Queens was drawn to make it as Asian as possible, but Asians are still only 45 percent, with Hispanics at 25 percent and whites, 23 percent. That’s enough Asians.

Grace Meng has represented the district since 2013.

In addition to 100 or so districts that are more or less naturally minority-majority, 40 to 45 districts have been distorted to conform to the Voting Rights Act to make them majority non-white. The act also applies to state legislatures, so of the 7,383 such seats, approximately 1,000 were gerrymandered to make sure BIPOCs were elected.

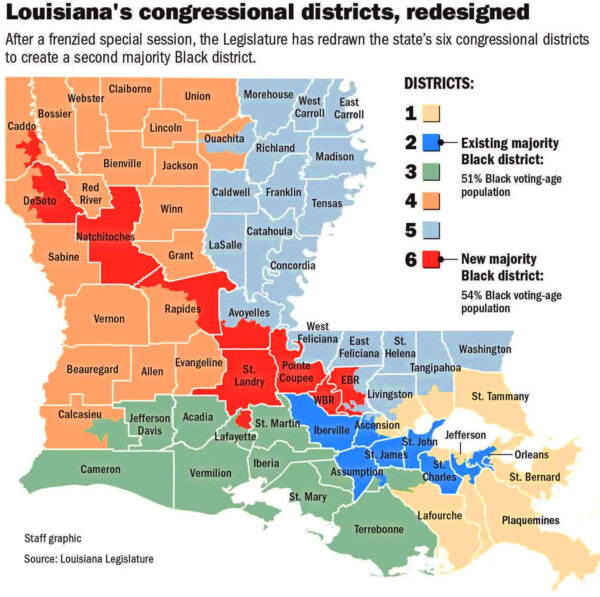

The Supreme Court has now said it will look into whether racial gerrymandering is constitutional. The case has to do with Louisiana. Here are its six congressional districts, drawn in different colors.

The red one (District Six) and the blue one (District Two) are majority black and the other four are majority white. Since the state is one third black, the thinking was that blacks should have one third of the congressmen, which means two out of the six districts. This brought about red District Six, which is obviously an artificial creation designed to scoop up enough blacks to make a majority.

This has been challenged on 14th-Amendment equal-treatment grounds. The claim is that BIPOCs are being unfairly favored by artificial districts that give them artificial majorities and more Congressmen than they deserve. It’s like unfair race preferences in college admissions.

Democrats love these districts. Every majority-black and majority-Asian district and most majority-Hispanic districts have Democrat congressmen, so if the gerrymanders have to be redrawn, the Dems could lose 30 or 40 seats.

Democrats are shrieking.

Which side should we be on? More race-conscious Dem districts, or districts that ignore race and are more likely to be Republican? The country is better off with fewer non-whites and more Republicans in Congress, which is what happens without racial gerrymandering.

On the other hand, I like the principle of recognizing that different races have different political interests. Some people argue that if blacks are 13 percent of the population, they should have 13 percent of the seats in Congress set aside for them.

I would favor that, if that thinking went all the way.

If blacks — and by extension, Americans of all races — need their own representatives, they need their own police, judges, schools, neighborhoods, institutions, and media. They need their own countries. But only a few of us understand that this is the only way to preserve our race and civilization.

That’s the trouble with white so-called conservatives. They are the only people in America who still believe in civic — non-racial — nationalism. Everyone else wants a piece of our country because we made it great. And they’ll happily take more and more of it until we are a pointless minority.

We need to support the principle that racial politics are inevitable and that they should be comprehensive — to the point of separate nations.

We have the right to be us, and only we can be us. And only we can save us.

The post Race-Based Congressional Districts appeared first on American Renaissance.

American Renaissance

R1

R1

T1

T1