In the first part of this review of Ricardo Duchesne’s Greatness and Ruin, I looked at some highlights from the book’s earlier chapters explaining the rise of the West, as well as his argument for its objective superiority to China and other non-Western civilizations. In his final chapter, the author turns from the greatness to the ruin of the West, most clearly seen in the crisis brought about by “antiracist” thinking and the mass immigration it has inspired.

He begins by remarking on the inadequacy of a recently popular diagnosis which traces our predicament to cultural Marxism. It is not entirely without merit: There really was a Frankfurt School of Social Research staffed by Marxists who shifted their attention from the economic and political concerns of classical Marxism toward broader cultural issues, thus producing a body of thought justifiably labelled “cultural Marxism.” Moreover, such thinking became extremely influential within the American academic world, and was the source of much of what came to be known as “political correctness” in the 1990s.

But Dr. Duchesne is correct, I believe, to see these developments as surface phenomena best understood against the much larger and deeper background of our civilization’s loss of self-confidence, a loss due in large measure to the radicalization of certain of its own inherent tendencies. It was only against such a background that the Frankfurt School was able to achieve what it did.

Liberalism: source of Western ruin

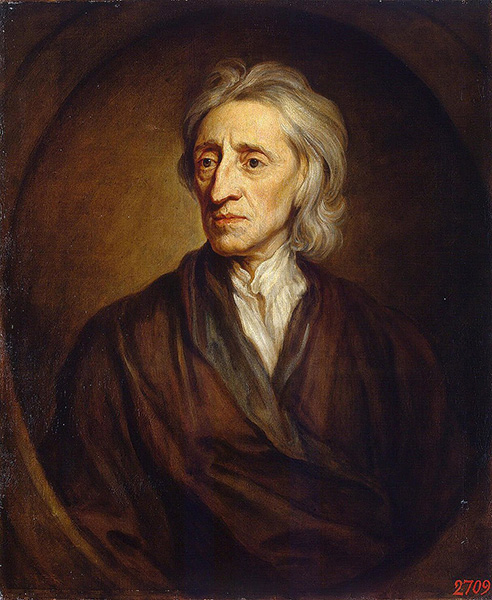

The West’s weaknesses are rooted in liberalism, not Marxist radicalism. Yet liberalism itself is rooted more deeply in European individualism, which goes back at least 2,000 years before liberalism’s 17th-century origins. The heart of liberalism is its view of man as naturally an individual, existing independently of his fellows, and a consequent understanding of society as artificially instituted by men for their convenience and protection. The new doctrine found its first full expression in John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government (1689).

In fact, as Dr. Duchesne demonstrates at length, individualism is not natural or primitive but represents an historical achievement of European man. Before the rise of Western civilization, the human world was

one of intense kinship relationships characterized by a corresponding psychology that was clannish, conformist, deferential, and highly context sensitive, without the ability to detach objects and persons from particular settings, and thus without the ability to generate abstract concepts and think analytically.

Things began to change with the development of the Indo-European aristocratic warrior band not based on kinship — a social institution in which warriors could compete for glory and reputation. In Greece during the classical era, the power of kinship was further broken in favor of civic bonds that allowed for the rise of self-government through deliberative assemblies that rewarded talent independently of family connections. Such developments were a precondition for the discovery of a rational mind present (at least potentially) in each individual man — a locus of thought independent of social relations and subjective feelings, and capable of grasping objective truth.

The rise of Western individualism and self-consciousness was thus well under way in classical times, and they continued to develop and strengthen for many centuries thereafter. By Locke’s time, individualism was so well-developed in Northern Europe that it had come to be taken for granted. The way was thus open for a new speculative teaching that imagined radical individualism as the native and natural condition of the human race.

Despite the seriousness of this fundamental error, the central role liberalism grants the human individual makes it a quintessentially European doctrine. It is impossible to imagine the theory of an individualistic “state of nature” and subsequent establishment of political society by means of a “social contract” originating in a non-Western kinship-based society such as China. As Dr. Duchesne writes: “Liberalism is almost epigenetically rooted in the historically evolved psychology of Europeans.”

Liberalism grew, flourished, and developed many subvarieties, influencing Western institutions for the next two and a half centuries without ever appearing to threaten our civilization with destruction. One important variant was the moderate republican liberalism of Thomas Jefferson, with its recognition of the primacy of the public good over private interests and fear of the corrupting influence of uncontrolled commerce. As the author notes, the relatively benign effects of early liberalism were due to its having been developed when

the vast majority of people [still lived] in an unchanging landscape dominated by the alternation of the seasons, going to church, creating large families in customary ways, rarely moving out of their place of birth. . . . Liberalism “worked” because it was sustained by important nonliberal qualities from the past.

We should note that the individualism characteristic of Western civilization was itself always relative, leaving a significant place for kinship ties in the ordinary lives of Europeans.

German historicism: liberalism’s defeated alternative

Liberalism came to play distinct roles in the histories of various European countries. As the author notes, “nineteenth century nationalism in France, Britain and America came along with liberal universal values about the natural rights of man and the sovereignty of the people against monarchical and aristocratic traditions.” In Germany, by contrast, liberalism remained weak. And this is significant, for as Peter Watson writes in The German Genius (2010), Germany was the dominant intellectual force in Western civilization between about 1750 and the 1930s. It behooves any people suffering from a dangerous excess of liberalism, therefore, to consider the example of Germany.

Among the leading traits of German intellectual life in the 19th century was a widespread concern with history. As Dr. Duchesne explains, German scholars emphasized “the critical analysis of historical documents” and a “commitment to factual accuracy,” while promoting “the professionalization and specialization of history as a university discipline.” This concern eventually resulted in an entire new school of thought called “German historicism.” One of its exponents, Friedrich Meinecke, considered it his country’s greatest contribution to Western thought since the Reformation and “the highest stage in the understanding of things human attained by man.” In Dr. Duchesne’s words, historicism

provided Europeans with a historical consciousness by explaining how humans are historically conditioned, not within history conceived as a linear progression following universal scientific laws, but as members of a particular land, nation, and culture. There is no universal “man.” Humans can only be understood in terms of their unique history and customs.

Because the historical sciences deal with purposeful human beings and with unique and unrepeatable events, historicism rejected any attempt to apply the methods of the natural sciences to human affairs. It also refused to force history into any linear pattern of progress or overarching theory, preferring to see each nation, culture, and historical era as irreducibly unique.

The German historical school’s emphasis on the radically conditioned character of human understanding sometimes led it into confusion: the sort of confusion that might infer from Euclid’s Elements having been produced in ancient Greece that Euclidian geometry was valid only for ancient Greece. This led some historicists into the dead end of relativism, and we will not argue with those who criticize the school on that account. But this is not the whole story of German historicism. As Dr. Duchesne writes:

What Western historians today call “the crisis of German historicism,” with unresolvable arguments about the historical relativity of truth, has obscured the fact that the true crisis faced by this school . . . is the suppression of its powerful critique of liberalism. German historicists advocated a nationalism with values culture-bound to Germans’ particular history. It also emphasized the priority of the freedom of the Germans as a people over the abstract rights of individuals.

For freedom is not the same thing as individualism. Most champions of liberal individualism fail to recognize something that the German historical school emphasized: the close dependence of human thought on subtle and complex lines of habit, tradition, and social relationship. Even the most committed individualist is no Robinson Crusoe, but a man whose thinking is shaped by his social and historical setting in all sorts of ways of which he may remain unaware.

Anyone who understands this is unlikely to remain content with Locke’s view of society as the product of a rational agreement between pre-existing individuals. But the rejection of liberal theory does not imply an endorsement of despotism. Rather, the non-liberal will recognize superpersonal formations such as the family, the local community, the trade union, the church, the college, and the profession as the true building blocks of society. Politically, he will not limit himself to the defense of individual rights, but also seek to create social and legal conditions within which autonomous groups may prosper (see Part I of this review on Medieval Europe with its “voluntary associations such as urban communes, merchant associations, guilds, monasteries, and universities with corporate rights of self-government each according to its own law”). This nonliberal way of thinking will foster a citizenry more mindful of its duties than its rights. It will also attribute a legitimate role to the sovereign state in restraining the harmful effects of human appetite and regulating disputes between the autonomous private bodies of which society is composed.

Such ideas predominated in Imperial Germany and were typical of the historical school, which sought to defend the uniqueness of German history against the liberal attempt to impose a uniform order of nation-states based on individual rights:

German nationalism and geopolitical power in the mid-nineteenth century coincided with modernization [but] Germans wanted a path that would be balanced with its unique history, respect for aristocratic authority, and a propertied and cultured middle class working in union with a powerful state acting as the common point of the German people. They sought the highest capacity for independence and strength among the competing powers of the world rather than a state acting at the behest of a dominant capitalist class pursuing its own interests, or at the behest of a democratic mob easily controlled by private interests. To be somebody, a people must have a strong state, united and independent of other states.

Nineteenth century Germany even developed its own style of economic thinking. It embraced

modernization and liberal values judged to be consistent with the collective interests of the nation [but] rejected the liberal idea that economics was a science capable of generating principles and policies with universal validity without considering the particulars of each nation. Treating citizens as faceless producers and consumers, as if they had no bond with the national community, was a mistake. [German economists] accepted the Aristotelean doctrine that man is inconceivable outside the State, that no man is an island, but interwoven from birth to death with a national culture. The State is not, as Locke and Smith saw it, a conglomeration of individuals seeking their self-interest, but a reflection of the need of man to belong in a community. A nation-state can’t be concerned only with material production, but must concern itself with the totality of life.

As Dr. Duchesne notes, the nation informed by such ideas was hardly groaning under the despotism that liberals fear:

Germans during this period enjoyed considerable individual liberties, universities open to merit, a constitutional monarchy, rule by established procedure, a high degree of economic freedom, and a dynamic cultural atmosphere which encouraged the full development of individuality. German historicists believed in a society in which the individual was free while being simultaneously integrated into the German nation.

In their view, this was superior to liberalism’s vision of a lonely crowd in which everyone pursues his own merely private happiness in a state of alienation from the historical heritage of his country and people. We 21st-century Americans may be in a better position to appreciate the soundness of this perspective than were 19th-century Germans themselves.

The downfall of the German historical school had less to do with any legitimate or principled objections to its ideas than with Germany’s defeat in two world wars. After 1945 especially, writes Dr. Duchesne, the victorious Western allies decided that only nations founded on individual rights were legitimate, and that National Socialism and the war could be blamed on “intolerant German historicist ideas about the Volk.” The entire West German Federal Republic had to be given a “thorough re-education in enlightenment progressivism.”

This ambitious program of mass psychological manipulation became known as “denazification.” It is important to understand that this was never narrowly conceived as an effort to wean the population from support for the NSDAP and Hitler personally; it also sought to cast much of Germany’s past in a bad light. Deeply learned thinkers of the 19th century were absurdly recast as nothing more than “precursors of fascism” whose ideas had led to the crematoria of Auschwitz. By the 1960s, once a new generation with no memory of the Germany of before 1945 began coming of age, this reeducation program began succeeding beyond anyone’s dreams. Many Germans now quite sincerely believe their ancestors were scoundrels, and not only those who lived during the National Socialist period.

How liberalism lost its moorings

Of course, this liberal-progressive variant of brainwashing was not restricted to Germany, but soon spread throughout the West. As mentioned above, the relatively benign liberalism of earlier days was sustained by a culture that had not lost all connection with its deeper nonliberal roots. But, as Dr. Duchesne observes: “The 1960s saw a final push by liberalism to discredit, mock, devalue, and identify as oppressive these remaining traditions.” It is as if the entire West decided to treat itself as a defeated enemy, subjecting itself to an aggressive and ruthless program of denazification. Liberalism, a way of thinking centered on preserving and maximizing human freedom, was metamorphosed into an instrument for the destruction of our civilization through the demonization of our ancestors and demands for our replacement by hostile outsiders. How was this possible?

The essential clue is to be found in liberalism’s peculiar notion of “tolerance,” which conceals an irresolvable tension. As the author notes, “liberalism is unlike any other ideology or traditional normative order in that it lacks a metaphysics about the ultimate nature of reality, about the highest values in life, or what ends individuals should pursue.” The liberal’s ideal political order adopts a stance of strict neutrality on the most important questions of life, questions traditionally addressed by religion.

Historically, this ideal arose as a response to the 16th- and 17th-century wars of religion. Few people today have any idea just how destructive that historical episode was. The men for whom it was still a recent memory — not unlike the men of the early post-WWII era — were deeply concerned to prevent any repetition of the civilizational trauma they had lived through. The response of early liberalism was to advocate the establishment of a religiously neutral form of government that would tolerate various teachings about God and the highest values in life, but would not endorse or promote any such views itself.

Liberals were not slow to notice, however, that such toleration could never be universal or absolute for the simple reason that a particular religion might insist on its own unique rightness, entitling it to the exclusive patronage and protection of government. Such a religion would, of course, be incompatible with the ideal of religiously neutral government itself. This was the original form of the liberal dilemma, which persists to this day, of whether or how far one can afford to “tolerate the intolerant.”

And the issue was by no means merely theoretical for the early liberals; they saw Catholicism as precisely such a religion due to the universal claims of the papacy. In his celebrated Letter on Toleration, John Locke expressly excluded Catholicism from the religions his supposedly religiously neutral government would tolerate. Of course, doing so seriously limits the effectiveness of Lockean liberalism as a means of resolving the disputes that led to the wars of religion, since those wars had mostly pitted Protestants against Catholics.

John Locke

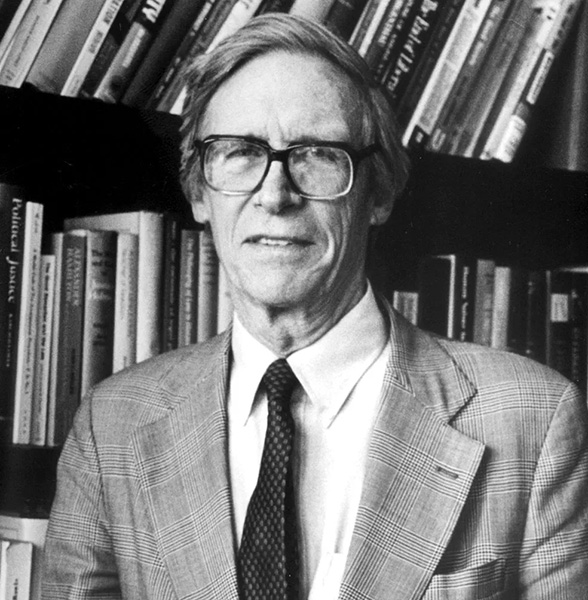

Dr. Duchesne points out that John Rawls, the most celebrated liberal thinker of the 20th century, similarly distinguished between “reasonable” doctrines that recognize the right of others to disagree and “unreasonable” doctrines that do not, and believed that Catholicism remained “unreasonable” until 1965, when the Second Vatican Council issued its “Declaration of Religious Freedom.” Liberalism, therefore, does not appear to have made much progress resolving its internal tensions in all the generations after Locke. But how impressive is a “tolerance” that would not have tolerated the historical religion of Europe until 1965?

From John Locke to John Rawls, liberal thinking has been forced by its own internal logic to adopt a kind of two-tier thinking. It must distinguish between beliefs and commitments distinct from but not incompatible with liberalism itself, which it offers to tolerate, and those that threaten the continued existence of liberal institutions, which it must suppress in order to survive.

Dr. Duchesne puts it this way:

Religious parents can teach their children the traditional view that a woman’s place is in the home; however, if parents teach their children illiberal political views that deny the equal civic status of women, encouraging their children to advocate and act on those views in the public sphere, then the government would have legitimate grounds to take action against such ways of raising children.

But how serious is any belief that accepts its own exclusion from public advocacy? Under a liberal regime, only liberal beliefs can be taken with perfect seriousness. And their promotion can become extremely aggressive:

The very cultivation of tolerance, reasonableness and open-mindedness entails creating a political culture, across all institutions, within families and private businesses, wherein liberal attitudes and behaviors are validated, celebrated, and incentivized, at the same time as nonliberal perspectives and behaviors are discouraged and marginalized. [Thus,] private businesses now mandate “diversity, equity, and inclusion” without allowing any dissenting voice.

Hence a doctrine originally aimed at restricting the public authorities to a neutral role has ended by politicizing every aspect of life.

At first glance, the exclusion of “intolerant” beliefs from the toleration offered by liberalism seemed like a minor qualification amply justified by the need to keep the liberal system functioning. But from the very beginning, the largest religious tradition in Europe was among these exclusions, and new and unexpected things keep getting added to the list. Since the 1960s, most of our civilization’s inherited folkways and the beliefs associated with them — those that formerly tempered the practice of liberalism and kept it from spiraling out of control — have come under attack as forms of “intolerance” incompatible with liberalism, and therefore as undeserving of toleration.

Today, liberals promote the right of men to become women. Such personal autonomy is, however, jeopardized by the continued existence of people who maintain that such a transformation is not possible, and who refuse to keep their mouths shut. And we find liberals advocating with the fervor of the Spanish Inquisition the hunting down, silencing, and punishing of such people — all in the name of freedom and toleration. It amounts to a reductio ad absurdum of liberalism itself.

From liberalism to antiracism and demographic replacement

This irresolvable tension within liberal thinking has recently played itself out in an especially remarkable and dangerous way with regard to race and racial differences.

A central liberal idea is that moral legitimacy derives from the free consent of contracting parties. This is why Locke conceived the state as derived from a “social contract” between originally free and stateless individuals. An important consequence of this view is that liberals have never been able to acknowledge the existence of obligations not traceable to any free agreement. They cannot explain, for example, the validity of the Biblical injunction to “honor thy father and thy mother,” since we have not chosen our parents.

By the same token, liberals eventually came to notice that racial identity is not an object of choice, since it is an inheritance from one’s ancestors. So they demanded reforms aimed at guaranteeing that no citizen’s choices or possibilities in life could ever be limited due to racial identity. This is the source of modern liberalism’s demand for an end to racial discrimination. But it is about as realistic as demanding a society in which everyone can choose his own parents. Many millennia of differing evolutionary history cannot be wished away.

As Dr. Duchesne notes: “It was from the 1960s on that liberals would start a hard drive for equal rights in all respects for different races.” He recounts some of the legislative landmarks of racial liberalism in the Anglosphere. Since the goal aimed at is utopian and unachievable, successive laws have become ever more comprehensive and enforcement provisions ever more draconian. Government power and intrusiveness in private relations have grown enormously. Over time, whites have been made the scapegoats for the project’s failure — amounting to an ascription of guilt by race in plain contradiction with antiracism’s original goal of freeing men from the consequences of an unchosen identity.

The insistence on trying to force unchosen and natural human differences not to matter has also led to the suppression of research into such differences, all in the name of liberalism and tolerance. As Dr. Duchesne notes, this includes not only research into racial differences, but anything “demonstrating that in-group favoritism would be a good evolutionary strategy for Europeans.”

The battle against racial discrimination was then extended beyond national frontiers when it was discovered that immigration policies based on race or nationality violate the nondiscrimination principle of modern liberalism. Immigration might be limited, but such limitations must not be influenced by racial considerations.

Soon even this proved inadequate. By 1987, a disciple of John Rawls was arguing that since all forms of liberalism assume the equal moral worth of individuals and the priority of individuals over the community, they can offer no basis for “drawing fundamental distinctions between citizens and aliens who seek to become citizens.” Liberalism requires nothing short of completely open borders to ensure the demographic replacement of the racist natives of the West.

Now it has become apparent that immigrants are less individualistic than the natives of the West, and are therefore demanding public and legal recognition of their “communities” and their own exclusive organizations. Liberals have therefore exempted them from the requirement imposed on whites to renounce group identity. This is the origin of multiculturalism.

What liberalism can never do, however, is extend the recognition of group identity to the natives of the West itself. Liberalism has proven relatively tolerant of antiliberal doctrines such as Marxism, but is irreconcilably opposed to whites with “a sense of peoplehood, by virtue of their belonging, through birth and historical experience, to a particular nation.” John Rawls, for example, described any form of racial identity among whites as “odious.” Yet no liberal has ever explained why group identity among whites has a different and opposite moral status from group identities among non-whites — presumably because no justification for such a double standard can be offered.

John Rawls

Dr. Duchesne notes the continuing faith of the powerful that after just a bit more effort to socialize the rising generation properly, non-white immigrants will overcome their ethnic biases and become as individualistic and pluralistic as whites. But this is a pipe dream, because the unfolding of individualism within the European psyche and its subsequent embodiment in Western institutions took millennia.

It is not possible to turn the entire world into liberal individualists by importing them to the West and sending them to classes on how to think as we do. But it is possible to preserve a part of the world wherein a moderate individualism can continue to flourish. This will involve protecting the only race that has so far developed the necessary psychological mechanisms for it.

It will also involve freeing ourselves of the liberalism now cannibalizing the individualistic society that gave it birth — and not by replacing it with some new, “genuinely tolerant” form of liberalism. What is needed is a decisive break with liberalism itself. This means consciously recognizing that individualism is not the natural condition of mankind, but an historical achievement of our own race, as Dr. Duchesne has done so much to demonstrate in the pages of Greatness and Ruin. Concern for individual rights and dignity must always remain tempered by consideration of the common good, and that common good must include that of the nation and the race.

The post The Path of European Self-Destruction appeared first on American Renaissance.

American Renaissance

R1

R1

T1

T1