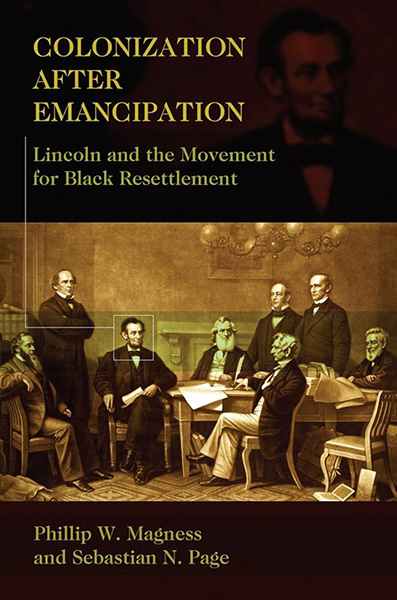

Phillip W. Magness and Sebastian N. Page, Colonization After Emancipation: Lincoln and the Movement for Black Resettlement, University of Missouri Press, 2011, 164 pp., $28.00 (softcover)

Abraham Lincoln is revered as one of the greatest heroes of American history. His face is on Mount Rushmore and he has a magnificent memorial in Washington DC. There are more schools named for him than for George Washington. Seventeen American counties are named for him, and he has appeared on more than 30 different postage stamps (Washington has been on more than 60 and Ben Franklin on more than 40). His face is on the penny and the five-dollar bill.

Lincoln defeated the Confederacy, but today, he may well be even more admired as the “Great Emancipator” who freed the slaves. This makes Lincoln’s views of blacks a great embarrassment for historians. None can ignore his June 26, 1857 explanation of why he opposed admitting Kansas as a slave state:

There is a natural disgust in the minds of nearly all white people to the idea of indiscriminate amalgamation of the white and black races . . . . A separation of the races is the only perfect preventive of amalgamation, but as an immediate separation is impossible, the next best thing is to keep them apart where they are not already together.

This passage from his 1858 debate with Stephen Douglas is just as straightforward:

I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races — that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality.

Lincoln thought slavery was immoral and should be abolished, but he believed that the only solution to the “negro problem” was racial separation. He was active in the Illinois branch of the American Colonization Society, founded in 1816, to “colonize” free blacks by sending them out of the United States.

It is well known that during the war, Lincoln actively looked for ways to colonize free blacks. In his first message to Congress, on December 3, 1861, he called for a budget to settle blacks outside the United States, and Congress voted $600,000 for this purpose. To put this into perspective, the entire federal budget the previous year had been a little over $60 million.

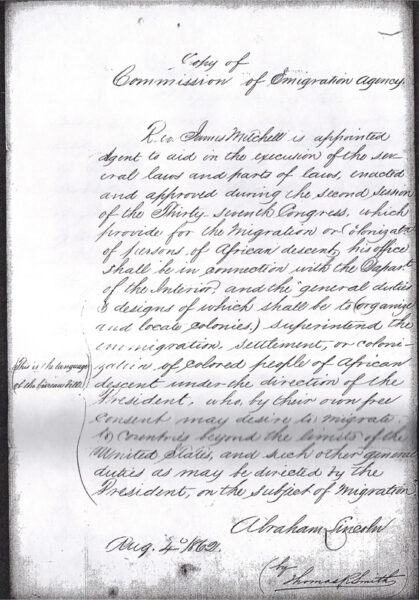

On August 4, 1862, Lincoln appointed James Mitchell as commissioner of emigration, with a mission “to organize and locate colonies, superintend the immigration, settlement, or colonization of colored people of African descent, under the direction of the President . . . .” Mitchell, who believed that separation was best for both blacks and whites, worked tirelessly to this end, even continuing after Lincoln’s assassination and briefly into the Johnson administration.

James Mitchell’s appointment as commissioner of emigration.

However, most historians argue that after Lincoln’s first efforts at colonization failed — in Chiriqui and on Île-à-Vache — he gave up on the idea and came to believe that the races could live in harmony after all. Some historians even propose a “lullaby theory,” claiming that Lincoln publicly promoted colonization only as a way to lull racist whites who would accept emancipation only if freed blacks were shipped out of the country.

Colonization After Emancipation, written by two academics in 2011, ably refutes these views. Phillip Magness, now at the Independent Institute, and Sebastian Page of Oxford have done primary research in long ignored archives to conclude that Lincoln was a fervent separatist to the day he died. The authors argue that Lincoln’s later efforts are little known, partly because his admirers don’t want to know about them, but also because bureaucratic infighting hamstrung the efforts and resulted in the disappearance of vital records. If this book were widely read, Lincoln’s reputation would suffer badly.

Early efforts

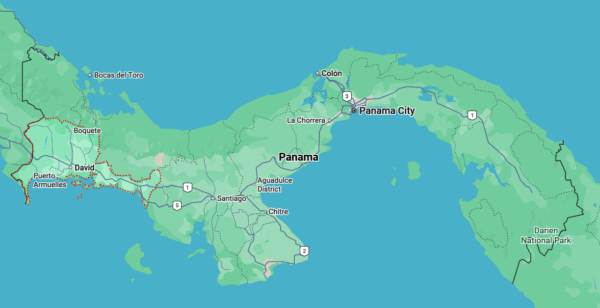

The best known colonization efforts were in the Chiriqui region of what is now Panama, and on Île-à-Vache, 6-1/2 miles off the coast of Haiti. The first was the brainchild of a Philadelphia businessman named Ambrose Thompson who had acquired development rights in the 1850s to several thousand square miles of the Chiriqui area of what was then the Republic of New Granada. There was supposed to be abundant coal, a natural harbor, and rich cropland.

Chiriqui region (inside the dotted line)

In May 1861, Thompson made a formal proposal to the US government to set up a coaling station for Navy ships. He would invest coal profits into cotton, sugar, and rice plantations that would sustain a large colony of freed blacks. By late 1862, 13,700 freed slaves had signed up for colonization, but the Chiriqui project failed before any arrived. The coal turned out to be low-grade lignite that was of no use to the Navy. Thompson also appears to have misused colonization funds to pay off personal debts.

What decisively sunk the project was stiff opposition by Central Americans who feared “a dreadful deluge of negro emigration . . . from the United States.” Luis Molina, the diplomat in Washington who represented New Granada, said it would never accept “a plague of which the United States desired to rid themselves,” and threatened to resist colonization by force.

The Île-à-Vache project got farther but was a fiasco. Bernard Kock, a cotton exporter, had a 10-year lease on the Haitian island to develop cotton plantations. Lincoln signed a contract with Kock and a group of financial backers, with the expectation of colonizing at least 5,000 freedmen. The Kock group promised to develop infrastructure, build housing and schools, give each family 12 acres, and pay them to grow cotton. The US government’s sole obligation was to pay the initial 453 colonists’ passage to the island.

Because Île-à-Vache was undeveloped, the land had to be cleared of dense vegetation, for which Kock provided no proper tools or draft animals to pull plows to break the ground. Corn and potato crops failed in a difficult climate and badly prepared soil. Smallpox and a painful flea-borne disease called tungiasis broke out, for which there was little medical care. Over 100 colonists died; the rest went into revolt and drove Kock off the island. Lincoln sent a rescue ship on March 12, 1864, and after 325 days of misery, the survivors left the island to return to America.

Kock’s reputation was tarnished — Lincoln accused him of “thievery” — but he was never charged with a crime. The greater casualty was the idea of colonization. After Thompson’s low-grade Chiriqui coal and Koch’s corner-cutting and 100 deaths, colonization took on an odor of corruption and incompetence.

Later efforts

Lincoln did not give up. He and his commissioner, James Mitchell, had extended negotiations with the British about sending blacks to two New-World colonies: British Honduras (now Belize) and British Guyana (now Guyana). They also negotiated a colonization treaty with the Dutch to send freed blacks to Suriname, just to the east of Guyana. Lincoln was just as serious about these efforts as the earlier ones that failed, but they are scarcely known. The authors of this book ask, “Why has the attempted colonization of the West Indies . . . escaped almost all historical attention?” They are the only historians who have seriously researched this question, and they have a convincing answer: Personal animosity between Mitchell and Interior Secretary John Usher, in whose department he worked.

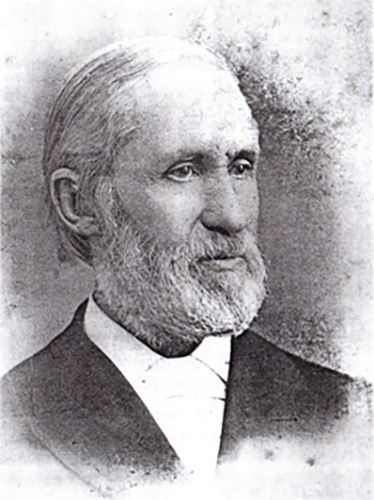

John Usher

Their hatred reached the point that Usher, who had previously supported colonization, not only sabotaged Mitchell’s efforts but cut off his pay and drove him out of his government office. As the authors note:

The policy mandate of the immigration office completely succumbed to the personal differences of its chief administrator and its cabinet department overseer . . . . The breakdown of this bureaucracy explains the decline in colonization efforts in 1864 more than any other single reason.

This was a great blow to colonization, but it also left a big gap in the historical record. Mitchell took all the records of the negotiations and plans for West Indies colonization with him. He managed to get the Johnson administration to reinstate his salary for a short time, but by 1866, the colonization effort was over. Mitchell kept the papers — including documents written in Lincoln’s hand — because he thought the government would not take care of them. He maintained a large trunkful of them until his death in 1903, and in his will, he instructed his nephew to have them published. The nephew never acted, and the papers disappeared. The authors, therefore, had to do much of their research for Colonization After Emancipation in the British archives.

James Mitchell

Mitchell first spoke to Lincoln about approaching the British in July 1862, even before the emigration office was set up. This is how Mitchell described the President’s reply: “If England wants our negroes, and will do better by them than we can, I say let her have them, and may God bless her.”

Britain had freed its own slaves in 1834, and this led to labor shortages, especially in Guyana, where 80,000 slaves had worked plantations. The British thought that with proper incentives, freed American blacks would be an effective labor force, especially because many would have had experience growing sugar, cotton, and rice, which were already profitable in Guyana. Lincoln met personally with the British ambassador to work out details. Private American and British citizens would recruit freedmen, the British government would pay for transportation, and landowners in Guyana and Honduras would hire the new workers and help them settle in.

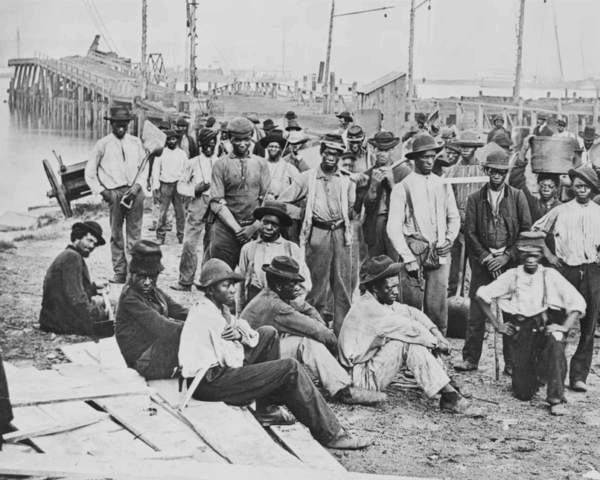

Freedmen

J. Willis Menard was a black man who had established himself as one of the most prominent black proponents of colonization. Mitchell hired him to work in the emigration office, making Menard the first black to hold an administrative position in the United States government. Mitchell sent Menard and another black colonization supporter, Charles Babcock of Massachusetts, to Honduras to look into prospects for blacks.

Babcock was especially enthusiastic, noting that Honduras had a relatively small population, in which free blacks might soon have considerable political influence. The abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison even wrote about Babcock’s enthusiasm in his paper The Liberator. The American consul in Honduras, however, wrote privately that he feared American blacks would be unhappy, and that his office would be swarmed by destitute blacks trying to go home. Lincoln himself fully backed the plan.

The British Colonial Office was eager for workers, and in 1863 and 1864, prospects for colonization seemed so good that planters in Honduras and Guyana were looking forward to the arrival of freedmen to help with the harvest. They never came, even though by April 1864, Guyana was even offering cash in addition to free transportation, in the hope of attracting black workers.

One problem was the British Foreign Office. Even late in the war, when a Union victory seemed all but certain, Britain was worried about future relations with a potentially independent Confederate States of America. The diplomats were afraid Southerners would be angry if Britain had enticed former slaves to leave the country. The Foreign Office insisted that labor recruiters seek blacks in no part of the United States south of Philadelphia — a condition that made recruitment much more difficult.

In the United States, Secretary of War Edward Stanton opposed colonization because he wanted to turn free blacks into soldiers to fight the Confederacy. On at least one occasion he so directly opposed Lincoln’s wishes that that President got angry at him.

Lincoln’s secretary of state, William Seward, also opposed colonization after he learned that the Chiriqui project would antagonize Central Americans, and later because the Île-à-Vache effort had been a failure. He was more a passive than active opponent, however, and mostly just dragged his feet on colonization.

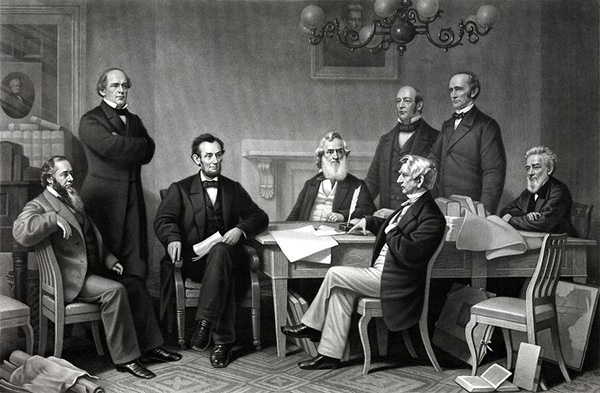

(left to right) Edwin Stanton, Salmon Chase, Abraham Lincoln, Gideon Welles, William Seward, Edward Bates, Montgomery Blair, Caleb Smith

He nevertheless worked closely with the Netherlands, which passed legislation specifically to make it easier for American blacks to emigrate to Surinam. Under Lincoln’s instruction, Seward even negotiated a treaty with the Dutch to build a framework for colonization. It was signed in March 1864, but the administration never submitted it to the Senate for ratification for fear it would not get the needed two-thirds majority — leaving Dutch planters just as disappointed as their British counterparts.

Why would ratification have failed? There had been a big change in mood among Republicans who had voted the $600,000 for colonization. As the authors write, the party had:

moved beyond its whiggish origins, its membership now augmented by an emboldened group of Radicals. Legislators who once entertained colonization as a way to keep the slave population from moving north after emancipation suddenly found partisan uses for maintaining a southern voting bloc in the free black community.

Republicans cynically decided to keep blacks — a race they considered undesirable — in the country because they expected ex-slaves to be pliant, faithful Republican voters. This was attractive to Northerners because very few blacks lived in the North and would have no effect on political outcomes even if they got the vote. In the South, where large numbers of whites would be denied the vote because they had supported the Confederacy, blacks — and thus Republicans — could dominate politics. For Northern whites, partisan advantage took priority over racial solidarity.

The 14th Amendment, which gave blacks the franchise, was just as cynically passed. When Congress voted on June 13, 1866 to propose it, not one of the 11 Southern states had been readmitted to the union, so Southerners had no say in the matter. Even by the time of ratification one month later, five Southern states were still outside the Union, so were not counted in the necessary three-fourths required for ratification, and for five of the six readmitted states, ratification was a condition for readmission (readmission was the only way to end Yankee military rule). Even some liberal historians argue that because of the exclusion of the South from the Constitutional procedure, the legality of not just the 14th Amendment but even the 13th, which freed the slaves, is dubious.

It is little known that during the failed Hampton Roads peace conference with Confederate representatives in February 1865, Lincoln is reported to have invited the Confederates to stop fighting, rejoin the Union, defeat the 13th Amendment by refusing to ratify it, and keep their slaves! The Emancipation Proclamation, he said, was “a war measure” that the courts might well find unconstitutional.

Lincoln consistently put the interests of whites and preserving the Union far above the interests of blacks, slave or free. As he wrote to Horace Greeley in August 1862, with the war well under way:

If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union.

Lincoln was deeply pessimistic about the prospects of blacks and whites living together, and the 1863 draft riots in New York City only deepened his pessimism. By then, Lincoln had issued the Final Emancipation Proclamation in an effort to make the war look like a moral crusade. Rioters opposed the draft because they didn’t want to fight, and many were incensed at the idea of fighting a war to benefit blacks. This is why they burned down the Colored Orphan Asylum, as well as many black homes and businesses. They lynched at least 11 blacks, and may have killed scores more. This only fortified Lincoln’s determination to separate the races.

It has long been recognized that General Benjamin Butler had a conversation with Lincoln about colonization just a few days before his assassination in April, 1865. Butler spoke about this conversation many times, but put it in print only in 1886. He summarized Lincoln’s comments: “I can hardly believe that the South and North can live in peace, unless we can get rid of the negroes. . . . I believe that it would be better to export them all to some fertile country with a good climate, which they could have to themselves.” Butler added that Lincoln had raised the possibility of sending blacks to Panama to help dig the Panama Canal.

While Butler was alive, no one doubted the truth of this report. It was only in the 1970s that historians began to discount Butler, arguing that he was known to exaggerate his war record, so that made his report of the conversation unreliable. However, as the authors of Colonization After Emancipation note, Butler never changed his account of his last conversation with Lincoln and, unlike his war record, he had no reason to embroider it.

Those who promote the idea of the egalitarian Great Emancipator place much weight—and rightly so—on Lincoln’s musings late in his presidency about the possibility of giving the vote to “very intelligent” freeman, especially to “those who serve our cause as soldiers.” However, he never pushed this idea with anything like the persistence with which he pushed colonization, and may well have seen it as compatible with colonizing as many blacks as possible.

Noted Civil War historian James McPherson is one of those who promote the “lullaby theory,” that an egalitarian Lincoln used colonization only to sugarcoat the prospect of emancipation. As the authors of this book note, that would mean Lincoln was insincere in making colonization part of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. They also point out that Lincoln made no special effort to publicize colonization even as he worked diligently to achieve it. Most Americans learned about the Île-à-Vache failure only with the news that the government had sent a ship to pick up the survivors. A lullaby does no good unless someone sings it.

After Lincoln’s death, people who were close to Lincoln insisted that his support for colonization never wavered. Navy Secretary Gideon Wells said that the President had been disappointed by the failure of colonization and that he hoped to revive it after the war. He said that in Lincoln’s mind, emancipation and colonization were “indissolubly connected,” and that colonization in fact “had precedence with him.”

Whatever justification Lincoln may have had for going to war to preserve the Union, this book leaves no doubt about his views on race. As the authors write: “Lincoln sought an answer to the dominant question at the end of his presidency, the future of race relations in the United States.” In this, he showed great wisdom of a kind his successors have lacked. President Ulysses S. Grant negotiated a treaty to annex Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic), in part, to serve as a haven for American blacks. The treaty failed in the Senate in 1870, largely because many Senators did not want to absorb a mixed-race territory and feared that the flow of non-whites would be into the United States, not out.

America’s inability to solve “the dominant question” at the end of the war was a matter of will. Few whites would have disagreed with Lincoln when he told a delegation of blacks in 1862:

You and we are different races. We have between us a broader difference than exists between almost any other two races. Whether it is right or wrong I need not discuss, but this physical difference is a great disadvantage to us both, as I think your race suffer very greatly, many of them, by living among us, while ours suffer from your presence. In a word, we suffer on each side.

We continue to suffer. We suffer worse than ever. Yet many Americans now deny their suffering and even claim that “diversity is our greatest strength.”

The post The True Face of the Great Emancipator appeared first on American Renaissance.

American Renaissance

R1

R1

T1

T1