Stablecoins In An Unstable System

By Christian Lawrence, head of cross-asset strategy at Rabobank

Summary

- The post-WW2 and Cold War global architecture is crumbling; systemic geopolitical and geoeconomic instability is rising; so are risks of geo-financial instability as fiscal deficits grow, public debt rises, and hopes for rate cuts meet sticky inflation.

- Against this backdrop, stablecoins may play a pivotal role – though ironically they are likely to create further instability before cementing an alternative.

- This report will explain what stablecoins are; why people may want to use them; why the US government certainly wants us to use them; and the hypothetical geopolitical and market implications of their roll out.

What are stablecoins?

Stablecoins have risen from a niche crypto product to front of mind for the US government, geopolitical analysts, economists, and market participants alike. What was initially viewed as an easier way to handle crypto risk on the blockchain is now seen as a potentially crucial variable in US debt management, USD reserve currency status, and global payment and trading systems.

Stablecoins are digital assets designed to replicate fiat currencies (Fiat money is government-issued monetary not backed by a physical asset), but we can break them down into the following subsets: commodity-collateralized, algorithmic, crypto-collateralised, and fiat-collateralised. The first three are still niche markets, while the latter is our main focus given it accounts for the overwhelming market share today and, more so, going forward.

Fiat-collateralised stablecoins are issued on the blockchain backed by a pool of fiat collateral held by a custodian. The current market cap is around $234bn and, according to the US Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC) report from April 30, more than 99% of fiat stablecoins are USD-pegged. Of the $233bn in USD-denominated stablecoins, more than $120bn is backed by US Treasury bills (The rest are collateralised by cash and bank deposits, reverse repo (often backed by US-Treasuries), corporate bonds, gold, Bitcoin, and other crypto assets). In short, this is all about the US.

The dominant USD stablecoin is Tether, with a market capitalization of $163BN. Cantor Fitzgerald, a US Treasury primary dealer previously run by Howard Lutnick (now Secretary of Commerce) is the primary manager of Tether’s collateral. In short, this is all about the US government.

Indeed, President Trump’s recent GENIUS Act (Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for US Stablecoins) requires the use of solely US assets such as T-bills, repo, reverse repo, MMFs, or bank reserves and aims to protect consumers in the digital market; ensure USD global reserve currency status; combat illicit activity in digital assets; and make the US the crypto capital of the world. To do so it will create a federal regulatory system for stablecoins 100% backed by US dollars or short term US debt (T-Bills), whose reserve composition must be reported publicly on a monthly basis (One could argue there are a few stablecoin-adjacent assets. One is Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC), state-issued tokens considered legal tender – digitised fiat. Another is tokenized deposits, bank-issued digital tokens on the blockchain representing a fiat deposit).

Why would people want stablecoin?

Security: stablecoins allow buying or selling of crypto without using an on- or off-ramp like a centralized exchange (CEX) with Know-Your-Client requirements. As crypto is not covered by Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insurance, using centralized exchanges leaves one vulnerable to the counterparty risk of said exchange. Some centralised exchanges are FDIC insured, but only for fiat holdings, not crypto holdings, so counterparty risk exists during the period that crypto sits in the CEX before it is exchanged for fiat. If one remains on the blockchain using stablecoins these can be kept in the holder’s own personal secure ‘wallet’4 that is not subject to counterparty risk.

Anonymity: selling crypto for stablecoin allows anonymity outside of the wallet address. With the blockchain, every transaction is visible by everyone, but the only information that can be seen beyond the transaction itself is the destination and origin wallet address. Who owns that wallet is unknown unless they use an on- or off-ramp that would reveal the wallet owners identity to the on-/off-ramp company, or if the wallet holder decides to reveal their identity publicly. In short, crypto without stablecoins involves moving into fiat which destroys the user’s anonymity.

Parsimony: stablecoins offer a quick way to transfer money at cheaper rates than fiat equivalents, particularly cross-border – and while avoiding SWIFT-system restrictions like sanctions.

Practicality: stablecoins can be exchanged for goods and services. For now that typically occurs online, but there are also growing stablecoin payment systems in shops. Most major US credit card companies also now support stablecoin transactions.

Prosperity: stablecoins cannot be interest-bearing instruments but can be deposited with third party institutions and receive payment/yield for doing so: in short stablecoin Money Market Funds (MMF) are possible, and indeed likely.

Why does the US want stablecoins? Debt

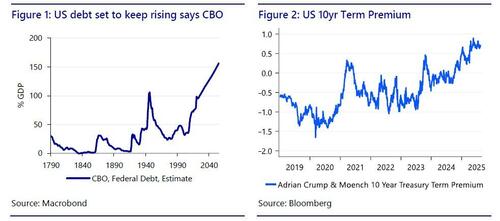

The US –like many Western economies– has a public debt problem. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates debt-to-GDP, at a post-WW2 level in a pre-war geopolitical environment, is on track to reach 156% by mid-century. Many view this as unsustainable and incompatible with the sustained reserve status of the US dollar, if not the stability of the US economy (Figure 1).

To avoid seeing longer-term borrowing costs rise significantly, the US Treasury has in recent years switched to issuing an increasing share of debt at the very short end of the curve, a tactic that is traditionally seen in emerging markets, not global financial hegemons. Indeed, part of the rationale to front-load issuance may be fears over slowing foreign demand for long duration US debt. We are not in the camp that thinks foreigners are ‘dumping’ US assets due to a loss of faith in its institutions and the rule of law, but policy uncertainty could be creating some indigestion for longer duration assets from private institutions. One could argue this is also partly reflected in the rise in term premium at the long end of the curve (Figure 2): it is the potential rise in yields from this perspective that the Treasury wants to avoid.

Notably, as stablecoins must be backed 100%, increased demand for the former will create forced buyers of the latter. In short, the US is incentivized to encourage the usage of stablecoins to soak up increased T-Bill supply.

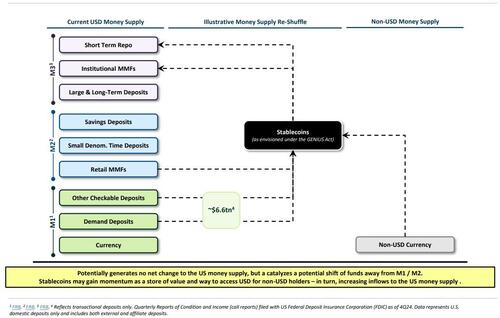

There is debate about whether or not stablecoins will result in an increase in the money supply. The Treasury states stablecoins “Potentially generate no net change to the US money supply, but catalyze a potential shift of funds away from M1/M2. Stablecoins may gain momentum as a store of value and way to access USD for non-USD holders – in turn, increasing inflows to the US money supply.” We argue the clearer dynamic is a change in ‘moneyness’. Essentially, USD stablecoins convert US debt like T-Bills/Repo (narrow inside money) into spendable cash (outside money). Holders might not be able to buy goods and services with a T-Bill, but they can with a stablecoin.

This raises immediate questions about how the Fed might view USD stablecoins. Would it be concerned about the money-supply impact as inflationary? Would it also look at the potential impact on the yield curve and its own balance sheet? Moreover, would it worry about future financial instability risks if a broader range of US collateral were gradually used beyond TBills?

How an independent central bank sits alongside a much more clearly Treasury-driven money supply remains to be seen – it is certainly something that the next Fed Chair, whomever that may be, will have to consider as part of their remit.

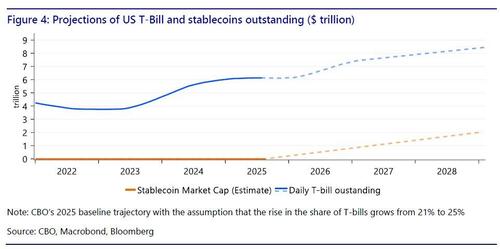

Figure 4 shows projected T-Bill issuance going forwards along with projected demand for USD stablecoins, which is estimated to hit $2 trillion in 2028. Note the debt path for T-Bills uses the CBO’s 2025 baseline trajectory with the assumption that the rise in the share of T-bills grows from 21% to 25%

Why does the US want stablecoins? The US dollar

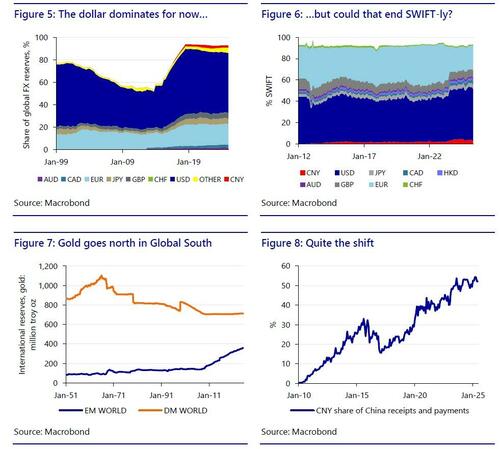

While issuing more short-term debt in high-debt economies is often associated with a weakening currency over time, USD stablecoins reinforce the US dollar’s global reserve FX status. Markets have been questioning this in the face of US deficits and debt, its aggressive sanctions on Russia, its retreat from the global economic and financial architecture it built, and rivalry within the current global system from Europe/the euro, and from the BRICS economies pushing non-SWIFT CNY, ‘BRICScoin’, or gold alternatives (Figures 5-8). Note we have written on before and remain sceptical of purported dollar replacements, but dollar avoidance is certainly taking place via de facto barter, with goods priced in dollar not used.

There is also a potential geopolitical angle. While we are unaware of any stablecoins that are currently designed in this manner, the smart contract code that ‘mints’ a stablecoin is programmable and editable by the owner. If a wallet is identified as being from a certain jurisdiction or deemed ‘undesirable’ then, if designed as such, it would technically be possible to prevent said stablecoin from being sent to another wallet, or to lock stablecoins held by it. In that respect, stablecoins could potentially be less fungible than physical fiat and offer more government oversight. While the potential programmability of USD stablecoins would make stablecoins designed that way officially unwelcome in jurisdictions with which the US has geopolitical tensions (such as China and Russia, for example), that wouldn’t mean they wouldn’t be popular unofficially, via a hard-to-control black market.

However, the primary logic is that USD stablecoins would be designed mostly for use by US allies as we head towards greater global bifurcation. There, via online platforms, private sector uptake may be seen for all the reasons already listed – plus FX diversification. While this means exchange rate risk for the holder (which in many emerging markets is seen as mostly unidirectional, even if the dollar is well down vs EUR, JPY, CHF, etc. in 2025), the ability to anonymously hold de facto US dollar MMFs, and to cheaply and easily remit and transact in them, could quickly cement USD stablecoins in many places. That’s true even in developed markets.

Indeed, recent trade negotiations, which ringfenced the US with tariffs, also show America has the ability to force others to accept terms they do not like. This could soon include payment for exports to it only in stablecoins, not dollars, or at least a portion of them, which would spread their international usage further.

Moreover, the US could lean on Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar –the source of much of Europe’s LNG, for example – to insist on payment for their energy in USD stablecoins: that would mean everyone who buys energy – except those who buy from the likes of Russia or Iran, etc. – needing to hold them.

Hypothetically, over time trade finance/trade could even start to involve –or revolve round– the Treasury not the private sector and the banking system: in the extreme, T-Bills would be akin to US export quotas of a sort.

Such neo-mercantilist economic statecraft may sound inconceivable to those accustomed to US/global free trade, it fits comfortably with a White House already embracing tariffs, making Nvidia pay a 15% fee to sell its AI chips to China (potentially extending that model to other firms too), and maybe taking a direct stake in chipmaker Intel, as the Pentagon takes a 40% stake in a US rare earths firm.

Indeed, USD stablecoins could work alongside the existing Eurodollar system of offshore fiat dollars ($120trn by some estimates), which is already a source of US financial power. Yet from now on, the creation of USD stablecoins, unlike Eurodollars, would necessitate the matching issuance of a US T-Bill, funding the US government, while the US could retain de facto control of who handled them even more than it does via SWIFT and sanctions.

In theory, this implies the need for an ever-growing amount of T-Bills for the US to allow USD stablecoin-based trade to expand, just as with the current Eurodollar system – the ‘Triffin Dilemma’. Failing that, they could become akin to a deflationary gold standard (and/or trade access to the US is necessarily de facto limited).

However, USD stablecoins can also be backed by USD repo, reverse repo, or bank reserves (even if the broader the range of assets involved the greater the potential risks of worrying financial instability become over time). That could be one solution. Yet the US doesn’t want to repeat past Triffin errors which it sees as having helped deindustrialise it: as such, hypothetically, USD stablecoins may gradually allow a separate ‘track’ to the broader fiat Eurodollar market just for trade. If so, any Triffin ‘bottlenecks’ may therefore be deliberate.

Why does the US want stablecoins? Geopolitics

It’s not an act of genius to see how USD stablecoins could benefit the US geopolitically and geoeconomically if one thinks outside the “because markets” box.

The White House is trying to remake the global system to its benefit, as it did in 1945 and after the Bretton Woods system collapsed in the 1970s. However, this time the US wants to ensure it centers around state-guided US reindustrialisation not private sector-guided US financialization to ensure its global military primacy: on the status quo trend that assumption is questioned by many.

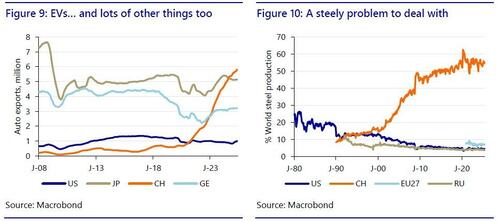

Crucially, while the BRICS are financial minnows compared to the US, they are an industrial and resource Goliath; China outproduces the US on all fronts (Figures 9 and 10), and its control of rare earths already sees it choking supply to western military industrial supply chains. The US, for the first time in centuries, finds itself the weaker economic party. Hence, something must change.

Every economy which the US can subsume into its own value chain, not China’s, and which it can arm-twist to help it reindustrialise via running much smaller bilateral trade deficits and pledged manufacturing FDI, is an extra stone in its slingshot. Moreover, many formerly US-leaning countries are refusing to make a choice between the two embryonic emerging blocs – that of the US and China – and may need ‘encouragement’.

USD stablecoins could clearly help forge a new US-centric system –with fewer US trade imbalances and more industry – vs that of China/Russia/BRICS.

The ‘Global Euro Moment’… of realization

This risk is now recognized in Europe, for one.

On 17 June, ECB President Lagarde spoke of a “Global Euro moment”5 as markets looked for potential alternatives to the US dollar; yet by 12 August, Politico reported this bubble was bursting due to fears of USD stablecoin penetration into Europe.

Indeed, a recent ECB blog titled “From hype to hazard: what stablecoins mean for Europe” argues, “Should US dollar stablecoins become widely used in the euro area – whether for payments, savings, or settlement – the ECB’s control over monetary conditions could be weakened. This encroachment, though gradual, could echo patterns observed in dollarised economies… such dynamics would be difficult to reverse given the network character of stablecoins and the economies of scale in this context. The larger their footprint, the harder these would be to unwind…. Such dominance of the US dollar would provide the US with strategic and economic advantages, allowing it to finance its debt more cheaply while exerting global influence.”

Of course, individual Europeans may not opt to use USD stablecoins given the efficiency of the Euro at home: but the tail risks above are exactly what the US is trying to achieve.

What is to be done? Not a lot

What could Europe, or others, do to stop the above scenario happening? Honestly, very little.

- Europe said it wouldn’t spend 5% of GDP on NATO: with one or two exceptions, it is.

- Europe said it wouldn’t strike an unfair trade deal with the US: it did.

- Europe appears to have been handed the bill, and front-line responsibility, for policing a ceasefire/peace deal between Russia and Ukraine; or the loss of its security order.

In short, if Europe — or others — try to block USD stablecoins operating as floated above it would risk reopening wounds on NATO, trade, Ukraine, energy flows, and/or the Eurodollar/Fed swap lines, etc. The latter not today, but perhaps under new management (Of course, these facilities are often in the US’s own interests in order to prevent financial instability that can also impact on it).

Additionally, if Europe wants its own stablecoins it doesn’t have the scale of collateral to match the US given the lack of Eurobonds (This is true for T-Bill equivalents but Europe obviously has many other assets it could collateralise: however, the advantages to be gleaned from doing so relative to the US remain questionable), and using Bunds would place further power in the hands of German fiscal policy. Meanwhile, a fragmented private-sector approach is unlikely to be welcomed by the ECB due to financial stability risks.

That leaves the digital Euro. Yet in January, President Trump issued an executive order stating, “Except to the extent required by law, agencies are hereby prohibited from undertaking any action to establish, issue, or promote CBDCs within the jurisdiction of the US or abroad.” That might create huge problems for European banks also using dollars.

Obviously, smaller global economies are even less well placed to contemplate issuing their own stablecoins to any positive effect.

Of course, neither China nor Russia will want to cooperate with USD stablecoins. Indeed, China is now talking about introducing its own stablecoins. Both USD and CNY versions would accelerate the ongoing process of global bifurcation already underway.

$tablecoins in an un$table $ystem

In conclusion, if introduced as we hypothesise, USD stablecoins may strengthen the US fiscal position and the global role of the US dollar. However, they are ironically likely to accelerate global geopolitical and geoeconomic instability in the short term: least so if US allies adopt them willing; most so if they resist aggressively.

Additionally, while not covered here, some fear that if USD stablecoins are introduced in a less mercantilist and more deregulated ‘Wild West’ fashion re: the USD collateral backing them, they could also increase US and global financial instability – though the GENIUS Act strongly suggests it is the mercantilist angle that matters most for now.

Even in the most benign scenario, USD stablecoins will still risk a less stable world at first as it is split more deeply between geopolitical, and currency, blocs, before perhaps finding a new stable geoeconomic status quo emerges.

That said, it’s very important to note that the current global system is already unstable. The massive trade imbalances and fiscal deficits run for years by many economies are widely accepted not to be sustainable – yet none of our global institutions appear capable of providing a guide or glide path towards a healthier economic equilibrium, let alone a geopolitical one.

As $uch, we $ee the entry of $tablecoins into an un$table $ystem.

Also available in pdf to professional subscribers.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 08/25/2025 – 06:30ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1