How The US Will Force Yields Lower Across The Curve

By Peter Tchir of Academy Securities

Forcing Yields Lower Across the Curve

We were already set to get a lot of economic data, especially on the labor front, compressed into a short week, and now we have to digest a court ruling on tariffs.

A federal appeals court ruled against (many/some/all?) tariffs imposed using an emergency law.

-

The tariffs will remain in place while the case proceeds.

-

It may go back to the lower court for another round, while also being pursued up to the Supreme Court. Nothing is “final” yet.

-

We discussed a couple of weeks ago that tariff rebate claims were trading at 25 cents on the dollar. Presumably, those are trading moderately higher after this ruling, but to a large degree, this news, which hit after the close on a long weekend, should be at least partially priced in.

Given that, we won’t dwell on this issue, for now, and will try and have some fun with the almost universal view that U.S. yield curves will steepen and the long end is very vulnerable to a spike higher in yields.

It is worth highlighting that the equity narratives highlighted in last weekend’s No Lonesome Doves continued to work this week.

The Consensus on Rates and the Fed

There is a lot of debate over whether Fed independence will be compromised or not?

That goes hand in hand with whether or not we will have “unnecessary” or “politicized” rate cuts?

For anyone answering “yes” to both questions, the natural conclusion is that we get rate cuts, but yield curves steepen and long end yields likely rise, possibly by a lot (yes, we mentioned that once already, but it seemed worth mentioning again).

As discussed on Bloomberg TV this week, we think that might be too simplistic. That people aren’t thinking “out of the box” enough and may well be underestimating this admin on their plans for yields.

Everyone Knows What Happened Last September

Since the risk that this pattern repeats itself is so obvious, it seems obvious (at least to the T-Report) that someone in D.C. is trying to figure out a strategy so that it doesn’t happen again.

Largely Playing Devil’s Advocate

For this report we can have some “fun.” We can think out of the box and suggest things that we would/might do if we were trying to implement policy that would help yields across the curve. Some of the things suggested are not things we would do or advocate for someone to do, but that isn’t the point. The point is to think about things that could be done, that would really hurt the consensus trade.

What could or will the administration do to Force Yields Lower Across the Curve (and hurt the consensus view)?

Guided By Bessent

There have been all sorts of statements (maybe even outrageous statements) on where monetary policy should be.

Bessent in a Bloomberg TV interview a couple of weeks ago said that Fed Funds were 100 bps too high. There was some wiggle room around his answer, but I think we can assume that Bessent sees 100 bps as the right range of cuts in the (very) near term.

Bessent has also spoken about 3, 3, 3. That was linked to 3% budget deficits, 3% GDP growth, and 3 million barrels of oil per day.

While I don’t think Bessent has given a specific target on 10s, he has been quite vocal about focusing on longer-term yields, not just the front end. Additionally, the administration has been very concerned about mortgage rates – a function of yields and spreads.

Maybe it is a stretch to assume something in the low 3% range would be a target for this admin on 10s, but that is the working thesis for this exercise.

Politicized Cut?

It is easy to turn this into a debate about whether a cut is politicized or not. But that might be missing the point.

-

The July meeting had 2 people dissent about the decision not to cut rates.

-

That was before the June jobs data was revised down sharply.

-

-

Powell came across very dovish at Jackson Hole, leading many (or at least us) to conclude that while “only” two dissented, the debate to cut or not may have been even more vigorous than he made it seem during the press conference or in the Fed minutes.

-

This is an “art” not a science. There have been plenty of people with a wealth of experience in economics and markets calling for rate cuts to have already started. Yes, there are people on both sides of the argument, but that is the point – there is no “right” answer. Having low quality data doesn’t make finding an answer any easier.

For purposes of this report (which is in line with our analysis and concerns on the labor front), 50 bps in September would be in the realm of justifiable.

Yes, many will disagree, and that is fair, but unless the jobs data across the board (ADP and the JOLTS Quit Rate are important to me) shows a robust improvement, I’d go with 50 bps and don’t consider that political.

Let’s just reflect on this for a moment.

If 50 bps is actually justified, why would the long end get hurt?

What many seem to consider a “politicized” cut, which sounds exciting to discuss, may not be, which means the alarm bells people expect to see in the market are less likely to materialize.

Independent versus Collaborative

Yeah, we are heading down a slippery slope here, but an “Independent” Fed doesn’t mean it has to (or should) “go it alone.”

Monetary policy, when implemented in conjunction with the Treasury Department (for example), may be the most powerful way to implement policy and get the desired results.

Whether it was during the GFC or COVID, we have seen the Fed work with other areas of the government to achieve their goals. That doesn’t mean the Fed isn’t independent, it just means that it is part of an overall strategy to achieve goals that it is in line with.

The Limitation of Fed Funds

Fed Funds as a policy tool seems weak at best. The “long and variable” time it takes for monetary policy to take effect when conducted through changes in the front end of the yield curve is almost comical.

-

In the months it takes for moves at the front end of the yield curve to work through the system, any number of other things can happen (trade wars, actual wars, technological improvements, etc.). It is difficult, even after the fact, to judge what some cuts or hikes actually did in the real world.

-

While ZIRP was a few years ago, many corporations, individuals, and municipal bond issuers locked in low rates, and are not that impacted by changes in front end yield. Whatever effectiveness conducting monetary policy via front end yields had has diminished since so many (other than the U.S. government itself) took advantage of lower for longer to protect themselves against changes in interest rates.

We’ve thought out of the box before, why not again?

Favorite Example

This was one of the “scariest” charts as COVID wreaked havoc on bond markets.

VCSH is an ETF that tracked 1 to 5 year corporate bonds. A 1% move in a short time is a relatively big deal. It fell around 12% in a matter of days. The discount to NAV was exploding. The ETF Spiral™ was in full effect (the arbitrage of selling bonds and buying the ETF, in times of stress, tends to accelerate and amplify the stress). Then the government announced a plan where the Fed (with money from the Treasury Department if I remember correctly) would buy ETFs.

The problem was literally fixed overnight.

Despite the fact that the mechanism to get the funding wasn’t set up. The ability to buy equities (which is what the ETFs are) had not been established. Again, I think it took weeks (if not longer) before any purchases of ETFs were made, but just the announcement fixed the problem.

Incredibly powerful and nothing that any amount of Fed Fund cuts was going to fix as effectively or quickly as this plan did.

One and Done?

We will start with this one, because timing wise, it might be easiest.

I’m not sure if this will work or not, but it deserves some consideration.

-

If the Fed goes 25 or even 50 in September, the market will immediately move to speculate on the timing and sizes of the next cuts. Especially those who characterize any cut as being politically pressured. There will be just as much uncertainty about the path and intentions of the Fed after the cut, as before the cut. Realistically, no one thinks we will get one cut of 25 bps and be done, so the speculation about Fed independence etc., will still attract a lot of attention and possibly push yields higher.

-

What about going 100 bps (which is where Bessent is and not far off from our 3 to 4 cuts this year), but committing to leave rates alone for several quarters unless the data changes dramatically one way or the other? Would people “trust the commitment”? That might be a stretch (even I’d be skeptical and I kind of like the concept).

-

100 bps would take Fed Funds to 3.33% (I like the 3s).

-

The 1 month versus 10 year yield spread is currently -9 bps. It would have to steepen by almost 80 bps for 10s to stay above 4%. A 100 bp cut would require a LOT of steepening, maybe more than the vigilantes can deliver to keep 10s above 4%?

-

Not my favorite idea, but something to think about. I do like “ripping the band-aid off” on cuts and getting to the endpoint (or potential endpoint) quickly rather than dragging it out (which is the “normal” procedure).

Attack Rent Inflation

Shelter is one of the biggest components of CPI.

“We” (and I use that term loosely) continue to use Owners’ Equivalent Rent as part of the calculation. If anyone can tell you succinctly and simply why Owners’ Equivalent Rent is still the right metric, I’d be shocked. It is a “calculation,” maybe even an “awkward” calculation. It is designed to have lags built in. Those lags presumably were to slow inflation from hitting the benchmarks in real time (by and large shelter costs go up). We were screaming at the top of our lungs during “transitory” that the shelter inflation in CPI was understating the real world rent inflation. Now “shockingly” it is working in reverse. The shelter component is artificially raising inflation benchmarks.

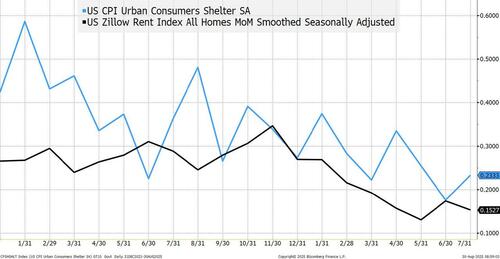

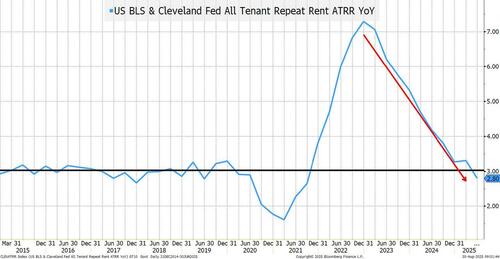

What I find interesting is that the Cleveland Fed has created their own metric, which seems to work well (I could only find a year-on-year version and it is a long weekend so didn’t spend too much time looking for a month-on-month version).

What little I know about charting this stuff is:

-

We are back to a pretty normal level of inflation for rents.

-

If the annual line is continuing to decline, the recent monthly numbers are lower still.

The Cleveland metric is below the almost 4% change in shelter inflation in CPI. Now, we wouldn’t normally quibble over a 1% or so difference in the course of a year, but since shelter is such a large component it is keeping inflation both stubbornly and inaccurately high.

If you want to attack inflation fears, start by attacking the data itself and highlighting this large component which virtually everyone agrees it is being overstated.

If you can combat some of the inflation fears, it should reduce the power of the bond vigilantes and the arguments of those who say it is a “political” decision to cut with inflation high.

Shift the Balance Sheets

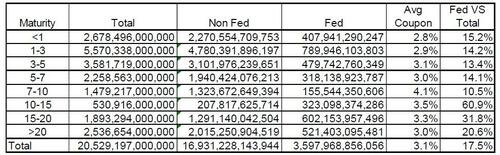

This gets to the heart of the problem. These are our current calculations of the Fed holdings of Treasuries by maturity (ignoring T-Bills, floaters, and TIPS).

The Fed balance sheet is skewed to the shorter maturities.

The Fed owns $2 trillion of bonds maturing in less than 7 years versus “only” $1 trillion of bonds maturing 15 years or more.

Let’s “imagine” that the Fed starts an “aggressive” Operation Twist. Selling bonds that mature in 3 years or less (most anchored by Fed Funds) would create about $1.2 trillion of purchasing power.

If they only bought bonds 20 years or longer, that would almost triple their portfolio size. Interestingly, “only” $2 trillion of bonds maturing 20 years or longer are outside of Fed control, so that would be 50% of the float! When you start thinking about what percentage of that is locked up in not available for sale accounts, it would be IMMENSE buying power.

That is extreme, but we start to get a sense of what can be done.

T-bills will be “anchored” by Fed Funds. So, the Treasury Department, if it doesn’t like where yields are (even with Operation Twist), could scale back issuance of longer-dated bonds even further, creating favorable supply and demand dynamics.

Don’t Fight the Fed.

Why would the Fed do Operation Twist?

Why wouldn’t they? They’ve done similar actions before. If they believe (and some do) that rates are too high, why would they be content to “only” set the front end of the yield curve? Why not, once again, interfere in the longer end of the bond market?

Heck, while I’m at it, why not shift out of some Treasuries and into mortgages? That might help the “spread” component of mortgages come down.

Also, there are $3.6 trillion of bonds maturing 10 years or longer, with prices below 90 cents on the dollar. That may create some interesting “accounting games” as selling bonds at par to buy bonds below par could be pitched as some sort of a gain? In the real world, it is far more complex than that, but possibly in an accrual accounting world, something can be done with these bonds to make it seem “even better” from either a deficit or overall debt standpoint. Bit of a stretch, but I’ve always been a fan of buying bonds at a discount.

YCC

That looks like the 3 letter code for a Canadian airport, but it is Yield Curve Control.

The U.S. hasn’t gotten into yield curve control in my lifetime, but it seems like each crisis brings new “unconventional” tools, which take us a step closer.

Japan had it recently.

This is an administration that is comfortable “setting the prices” on things like tariffs, so setting the price of yields seems well within the scope of what they might do.

If this was the 1990s and I said yield curve control, I’d expect people (including myself) to be aghast at the idea. But seriously, we have been on this slippery slope since at least the GFC, if not LTCM (Long Term Capital Management for those of you who didn’t have to deal with that mess).

Stablecoin Demand for Treasuries

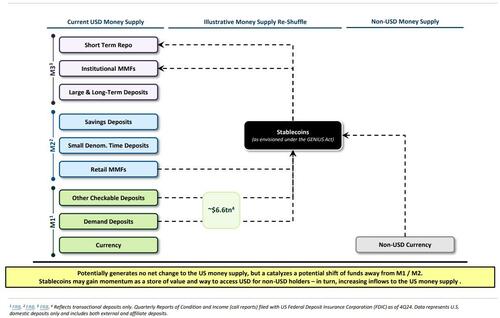

We’ve written in the past that Bessent expects $3 trillion to come into USD stablecoins (he really does seem to like the number 3).

That, if it materializes, would create demand for T-bills and short dated bonds.

Maybe we could issue more T-bills and fewer longer-dated bonds to satisfy that demand? Maybe we could sell bonds maturing in less than a year, to buy bonds maturing in 20+ years, to satisfy that demand?

I am excited for the opportunities in the stablecoin space given recent laws and regulations, but it might take more time to generate those sorts of inflows (new inflows into the USD forcing T-bill buying, rather than flows that cannibalize money from funds that also bought T-bills).

In any case, as this demand grows, it fits very well with things like Operation Twist, or a different maturity profile from the Treasury.

Any new net demand is good demand.

Gold Revaluation

According to AI, the U.S. has 8,133.46 metric tons of gold. I get confused between a tonne, a metric ton, and a ton, but it is a LOT of gold!

The book value is $6.2 billion (which is based on a price of gold of $42.222 per troy ounce that was established in 1973).

With spot gold almost $3,450 per ounce, the “market value” of the gold would be more than 80 times that amount – or about $506 billion.

Just “marking to market” gold would generate $500 billion of accounting revenue.

That is fraught with other issues. Annually, presumably, we’d have to adjust the value based on the price of gold. If the market thought the repricing was a sign that the U.S. would sell a lot of gold, the price would likely drop.

Since I presume the U.S. would sell some gold to fund some of its “Sovereign Wealth Fund” aspirations or make some deals, then the gains would be less, but still nothing to dismiss.

If you wanted to cause a distraction – announcing that you are revaluing gold and planning to sell it to invest in companies (or maybe even crypto currencies) might make everyone forget that the yield curve is meant to steepen!

Since I don’t understand why we hold so much gold as it is (I’m not in the barbaric relic camp, but am probably closer to that than the “sound/hard” money camp) I cannot see why we wouldn’t do some of this.

Would it lower the dollar? Probably, but for an administration trying to revert trade flow, a weaker dollar is a feature not a bug, even if they can’t say that out loud.

Tariffs

For now, despite the recent court ruling, it is worth resending our Tariff Revenue Charts which highlight the revenue that has come in so far (though subject to legal challenge) along with our rationale of why tariffs will take a long time to truly impact inflation.

Not the strongest argument right now after the court ruling, but some version of this argument remains relevant.

Bottom Line

It’s a long weekend and I could have written the umpteenth piece on the risks to the Fed and to the shape of the yield curve.

But, I thought it would be more fun to try to play devil’s advocate and create some discussion around tools and steps that could be taken to not just reduce the risk, but also potentially reverse the risk as the trade seems quite one-sided at this point and seems to not give the administration enough credit for trying to force things that we hadn’t thought could be forced.

It is too early to pound the table on flatteners, but that is the opportunity I’m looking for.

Nothing we’ve written or suggested today, if used, is helpful for the dollar, but, again, not sure that anyone involved in the U.S. efforts to import less and export more cares.

Enjoy your Labor Day weekend and get ready for all the labor data next week, all of which will be taken with a grain of salt given the recent adjustments.

Tyler Durden

Sun, 08/31/2025 – 16:20ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1