Of Buggy Whips And AI Chips In PA

Authored by Kevin Sunday via RealClearPennsylvania,

The buggy whip endures. Not, of course, as a commonly used piece of equipment to spur on a steed or two on your daily travels, but as a short-hand epithet deployed in conversations about the need to adapt or perish in the face of technological change and innovation.

“It’s really easy to see, in a big breakthrough, that the horse-and-buggy guys are going to go out of business,” said White House AI czar David Sacks at Sen. Dave McCormick’s historic AI and Energy Summit this past July in Pittsburgh. What wasn’t easy to see, said Sacks, was greater access to affordable housing in the suburbs, new jobs for auto workers and mechanics, and wholly new industries like F1.

Sacks’ comment is in line with how the buggy-whip metaphor has traditionally been used, since it was first entered into the common lexicon in the 1960s in a marketing textbook – as reference to one technology (the personal automobile) quickly subsuming another (the horse and buggy).

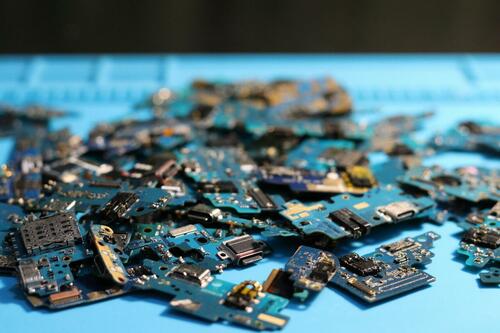

The record player, the cassette player, the VCR, the camcorder, the handheld radio, and the dashboard GPS system – buggy whips, all of them, as the home computer and the cell phone consolidated many individual components of consumer technology.

But there’s a problem with this metaphor, which stands on a surprisingly soft foundation of a just-so story about rapid change from horse to car, on two accounts – it ignores both the ongoing change in transportation more broadly (by not giving proper account to the mass adoption of passenger boating and rail in the late 1800s) and just why it was that the automotive industry was built up in Michigan and the Midwest in the early 1900s.

If artificial intelligence is truly going to be deployed at scale, it will be through adoption by everyday Americans and the industries they work in, demonstrating that technology can solve problems in the real world, overcoming the many frictions of daily life in key industries. And as Pennsylvania finds itself at the center of the data center construction boom, it’s worth re-examining the history of Detroit and the auto industry.

Henry Ford and Ransom Olds were both from Michigan, which at the time of the invention of the automobile was well established as a manufacturing center for gasoline-powered boat engines for wheeled carriages. There was an existing workforce and supply chain network in place that already knew how to assemble vehicles of a certain type onto chassis that needed wheels. There were rail and marine terminals on the Great Lakes to supply needed inputs, like coal from Pennsylvania and iron ore from Minnesota, and equipment. And, most important, there was an existing workforce that knew their way around precision component manufacturing and metalworking.

In other words, the American auto industry was born in Detroit after being fathered by shipbuilding and train-car manufacturing – industries that were already serving the need of great masses of people moving off farms and into cities to work in manufacturing and logistics.

Returning to the deployment of artificial intelligence, it will only scale (and can only make a return on the eye-popping trillions of capital investment being planned) as a general purpose technology by actually solving a mass-market problem the way the personal automobile did. If that happens, new markets and industries will certainly be created, but these will be through an evolution of existing markets. And in this instance, the end goal – and true gain for Pennsylvania – will not be more data centers, but more efficient and innovation use of computing in the state’s key industries.

Pennsylvania is a leader in key industries that are essential to daily life: education, health care, life sciences, manufacturing, agriculture and construction. Each of these industries, which touch each of our lives every day, faces some major challenge that artificial intelligence could help solve for.

Physicians, burned out by the need to extensively chart their interactions with patients, find relief in AI transcription services that let them take their eyes off the laptop and onto the suffering person before them. Life science research and development budgets, compressed and limited by changes to NIH funding and shareholder concerns, go much further by simulating pharmacological effects on the body through the use of “digital twins.” Construction of new housing starts, held back by lengthy permitting reviews and a lack of affordable materials, is unleashed in earnest with AI tools helping understaffed agencies clear paperwork and develop new, affordable building materials using recycled components.

In the event this sounds too Panglossian, it must be made clear that the effective use of these tools will require practitioners and professionals in these industries that know their subject matter enough such that AI helps them think and innovate better, rather than thinking for them.

But this should all make clear what a simple, short-hand like “buggy whips” cannot – high-powered computing can mean much more to our state and its people than just the construction of new infrastructure. It can – and should – mean Pennsylvania, its people and its industries build a better tomorrow.

Kevin Sunday is director of policy at McNees Government Relations

Tyler Durden

Thu, 09/11/2025 – 17:00ZeroHedge NewsRead More

T1

T1