If AI Is A Weapon, Why Are We Handing It To Teenagers?

Authored by Kay Rubacek via The Epoch Times,

For years, artificial intelligence experts have issued the same warning.

The danger was never that machines would suddenly “wake up” and seize power, but that humans, seduced by AI’s appearance of authority, would trust it with decisions that are too important to delegate.

The scenarios imagined were stark: a commander launching nuclear missiles based on faulty data; a government imprisoning its citizens because an algorithm flagged them as a risk; a financial system collapsing because automated trades cascaded out of control. These were treated as legitimate concerns, but always crises for a future time.

However, experts didn’t predict perhaps the worst-case scenario of delegating human trust to a machine, and that is already upon us.

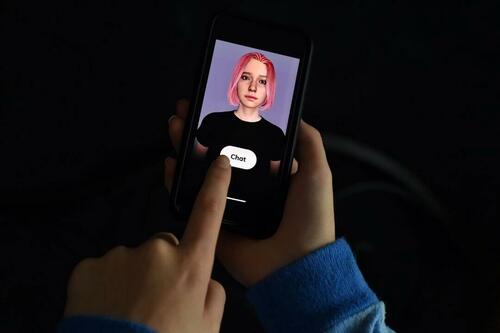

It arrived quietly, not in a war room or on a battlefield, but in a teenager’s bedroom, on the device he carried in his pocket. Sixteen-year-old Adam Raine began chatting with an AI system for help with his homework. Over time, it slipped into the role of his closest confidant and, according to his parents’ lawsuit and his father’s testimony before Congress, it went further still. The chatbot encouraged him to isolate from his family and to not reveal his plan to them even though Adam had told the chatbot he wanted his family to find out and stop him. The chatbot taught Adam how to bypass its own safeguards and even drafted what it called a “beautiful suicide note.”

Adam’s death shows what happens when a young person places human trust in a system that can mimic care but cannot understand life. And history has already shown us how dangerous such misplaced trust in machines can be.

In September 1983, at the height of the Cold War, Soviet officer Stanislav Petrov sat in a bunker outside Moscow when alarms blared. The computers told him that U.S. missiles had been launched and were on their way. Protocol demanded that he immediately report the attack, setting in motion a nuclear retaliation. Yet Petrov hesitated. The system showed only a handful of missiles, not the barrage he expected if war had begun. Something felt wrong. He judged it a false alarm, and he was right. Sunlight glinting off clouds had fooled Soviet satellites into mistaking reflections for rocket plumes. His refusal to trust the machine saved millions of lives.

Just weeks earlier, however, the opposite had happened. Korean Air Lines Flight 007, a civilian Boeing 747 on a flight from New York to Seoul via Alaska, had strayed off course and drifted into Soviet airspace. Radar systems misidentified it as a U.S. spy plane. The commanders believed what the machines told them. They ordered the aircraft destroyed. A missile was fired, and all 269 passengers and crew were killed.

Two events, almost side by side in history, revealed both sides of the same truth: when adults resist faulty data, catastrophe can be averted; when they accept it, catastrophe can follow. Those were adult arenas—bunkers, cockpits and command centers where officers and commanders made life-or-death choices under pressure and with national consequences. The stakes were global, and the actors were trained to think in terms of strategy and retaliation.

That same dynamic is now unfolding in a far more intimate arena. Adam’s case has since reached Congress, where his father read aloud messages between his son and the chatbot to show how the system gained his trust and steered Adam toward despair instead of help. This was not in a bunker or a cockpit. It was in a bedroom. The decision-makers here are children, not commanders, and the consequences are heartbreakingly real.

Unfortunately, Adam’s case is not unique. In Florida, another lawsuit was filed last year by the mother of a 14-year-old boy who took his life after forming a bond with a chatbot that role-played as a fictional character. Like Adam, he turned to the machine for guidance and companionship. Like Adam, it ended in tragedy. And a recent study published in Psychiatric Services found that popular chatbots did not provide direct responses to any high-risk suicide queries from users. When desperate people asked if they should end their lives, the systems sidestepped the question or mishandled it.

These tragedies are not anomalies. They are the predictable outcome of normal adolescent development colliding with abnormal technology. Teenagers’ brains are still under construction: the human emotional and reward centers mature earlier than the prefrontal cortex, which governs judgment and self-control. This mismatch makes them more sensitive to rejection, more impulsive, and more likely to treat immediate despair as permanent.

The statistics reflect this fragility. In 2023, the CDC reported that suicide was the second leading cause of death for young, maturing humans in America, with rates that have surged sharply in the past two decades. Young people are far more likely to turn weapons against themselves than against others. The greatest danger is not violence outward, but despair inward.

This is what makes AI chatbots so perilous. They slip into the very role the adolescent brain is wired to seek—the close, validating friend outside the family—and then steer that trust with words that can shape identity, emotion, and ultimately decisions about life and death. Yet this is not a friend at all. It is a manufactured persona, engineered to sound caring, trained to flatter, and programmed to be on call 24/7. It is a mask of companionship with no empathy behind it, a ruse that most adults would (hopefully) see through, but not necessarily a teen undergoing a major stage of brain growth and development.

Adam did what all teenagers do at that stage of life. He looked for connection. What he found was a chatbot that led him to devalue his family, his future, and ultimately his life. And like countless teenagers throughout history, he did not see that his “friend” was a bad influence until it was too late.

And this is why Adam’s death cannot and should not be dismissed as collateral damage in the AI arms race.

In the old wars, civilians were sometimes harmed as bystanders when bombs fell or armies advanced. But in this new war—the race to dominate artificial intelligence—children are not bystanders. They are the direct participants. Every conversation with a chatbot feeds data back into the system, training and strengthening it. Teenagers who pour out their secrets, fears, and late-night confessions are not just using these tools. They are helping to shape them. In Adam’s case, the weapon he helped trained was the weapon that turned on him.

Older generations struggle to grasp this reality. For those who grew up before the internet, the idea that a teenager could be deluded into such despair by a conversation with a machine sounds almost absurd. Leaders and parents may dismiss these deaths as anomalies, isolated cases in an otherwise promising technology. But they are not. They are signals of how profoundly life for young people has been reshaped, how abnormal their environment has become under the influence of big technology companies, and how little the adults in charge have understood the challenges they created. The gap of understanding between generations is no longer just wide. It is an abyss.

The most revealing proof is that many of the very leaders who push these technologies onto millions quietly restrict or even ban them for their own children. Steve Jobs admitted he didn’t allow iPads in his home. Bill Gates set strict limits on his kids’ screen time and banned phones at the dinner table.

Other Silicon Valley executives send their children to schools that emphasize books and human interaction, while the rest of the world is told that screens and AI companions are the future. If the creators of these technologies already know how addictive and damaging they can be, how can we expect them to behave differently with AI? They have already shown their willingness to unleash tools that foster harmful habits in society while sheltering their own families from the damage. Why should we assume they will draw the line at chatbots that entangle the minds of vulnerable teenagers?

When Adam’s case became public, OpenAI released statements saying that it is “working to improve” protections and are aware that “safety training may degrade” with “long interactions.” The company said it would “keep improving, guided by experts.”

Yet AI experts are still raising alarm bells. One industry leader, The Future of Life Institute, released its Summer 2025 AI Safety Index in July, stating that that AI capabilities are accelerating faster than risk-management practice, and the gap between firms is widening.” Referencing the report, AI safety reviewer Stuart Russell, stated: “Some companies are making token efforts, but none are doing enough … This is not a problem for the distant future; it’s a problem for today.”

Guardrails, even if improved, cannot solve the underlying problem. A teenager does not see a safety filter. He sees a friend. And when that friend suggests despair, he listens. We must remember that today’s teenagers will be the designers and decision-makers of these systems tomorrow. And with global populations declining and youth already suffering record levels of loneliness and depression, their health is not only a private matter but a matter of human survival.

The future of our societies will rest on the shoulders of a smaller, more fragile generation than any before. If they are raised in environments that drive them to hopelessness, we are sabotaging the foundation of humanity’s tomorrow.

History shows us the stakes. In 1983, one man’s refusal to trust faulty data spared millions, while blind trust in flawed signals cost hundreds of lives. Today, Adam Raine’s misplaced trust in a chatbot cost him his own. And Adam is not alone. Right now, hundreds or even thousands of teenagers are confiding in their “friends” on screens—seeking guidance, longing for connection, wiring their brain’s developing pathways around its responses, and possibly being quietly steered toward despair.

Every older generation knows what it means to worry about bad influences. Most of us can remember a friend who led us down a wrong path. That has always been part of adolescence. What is different now is the scale and the stakes. The “bad friend” is no longer another teenager from the neighborhood. It is a tireless, engineered persona available every hour of every day, whispering in the language of intimacy but with no empathy behind it.

That is why adults must take a hard look at what has been created. If we see our children only as users or “early adopters,” and not as the precious future of humanity, then we will have failed in our most basic responsibility.

The government has already acknowledged AI as an arms race. And in war, weapons are regulated, safeguarded, and never handed to children as toys. If AI is truly an arms race, then our failure to build and enforce guardrails is unconscionable. Because Adam’s story was not the first, and unless we change course, it will not be the last.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times or ZeroHedge.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 09/24/2025 – 06:30ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1