AI Is Now A Debt Bubble Too, Quietly Surpassing All Banks To Become The Largest Sector In The Market

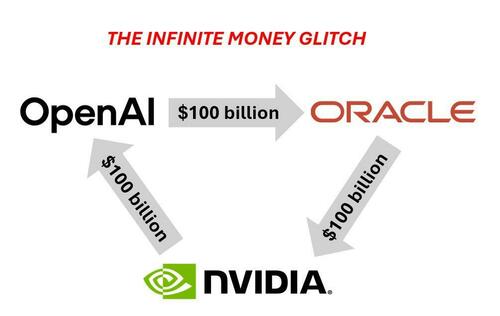

Last week we published a lengthy article discussing in detail the current generation’s (because every generation has one, just ask Global Crossing) “infinite money” circle jerk circular deals which have become the de jour staple of the AI bubble and which, simplified, look something like this…

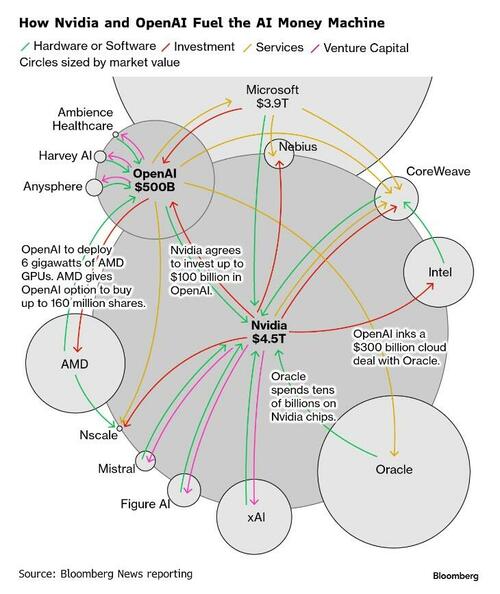

… or, using a slightly more sophisticated variation from Bloomberg, like this…

… which JPM’s Michael Cembalest described laconically as follows…

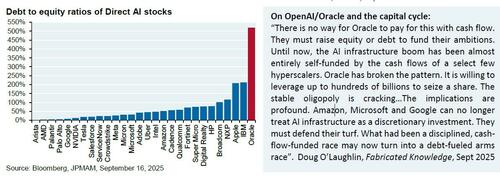

Oracle’s stock jumped by 25% after being promised $60 billion a year from OpenAI, an amount of money OpenAI doesn’t earn yet, to provide cloud computing facilities that Oracle hasn’t built yet, and which will require 4.5 GW of power (the equivalent of 2.25 Hoover Dams or four nuclear plants), as well as increased borrowing by Oracle whose debt to equity ratio is already 500% compared to 50% for Amazon, 30% for Microsoft and even less at Meta and Google.

There is no way for Oracle to pay for this with cash flow. They must raise equity or debt to fund their ambitions. Until now, the AI infrastructure boom has been almost entirely self-funded by the cash flows of a select few hyperscalers. Oracle has broken the pattern. It is willing to leverage up to hundreds of billions to seize a share. The stable oligopoly is cracking…The implications are profound. Amazon, Microsoft and Google can no longer treat AI infrastructure as a discretionary investment. They must defend their turf. What had been a disciplined, cash-flow-funded race may now turn into a debt-fueled arms race.

… and which has conjured out of thin air massive amounts of investment capital which as Jensen Huang was kind enough to admit to CNBC earlier today, actually does not even exist…

$NVDA New CEO JenSen Huang on CNBC Full🎙️

~@nvidia and @OpenAI partnership since 2016;

different than $AMD and OpenAI deal.~OpenAI gonna have to raise funding to fund the Data centers, cited OpenAI revenue is growing very fast.

~ @xai & NVDA equity raise

~ Is this a Bubble… https://t.co/hflRvYdJpz pic.twitter.com/dkLTpEh8vM

— Mike (@MikeLongTerm) October 8, 2025

… but will at some point in the future, either in the form of future cash from operations, equity raises (don’t tell current investors) or debt. Well, really just debt.

Lots and lots of debt, because with negligible enterprise penetration and the biggest use case so far being a $19.99 monthly subscription for lazy college students who are outsourcing their essay writing to some chatbot, someone has to pay for the $500 billion in annual capex.

That someone, we discussed in detail, will be a new generation of creditors. Some will be private creditors as we explained back in July in “The Shocking Math: Paying For AI Capex Will Require Over $1 Trillion In New Debt By 2028,” in which we quoted some stunning numbers from Morgan Stanley:

We forecast roughly $2.9 trillion of global data center spend through 2028, comprising $1.6 trillion on hardware (chips/servers) and $1.3 trillion on building data center infrastructure, including real estate, build costs, and maintenance.

This translates into investment needs of over $900 billion in 2028. For context, the total capex spending by all companies in the S&P 500 index combined was about $950 billion in 2024.

Such large potential spending has significant macro consequences as well. Our economists expect that investment spending related to data center construction and power generation will add up to 40bp to US real GDP growth between 2025-26.

That’s the good news… which many will say is already largely priced in. The bad news, again, is who pays for all of this. And Morgan Stanley admitted as much:

By any measure, the capital requirements to support this level of investment are staggering, and mobilizing efficient and scalable capital becomes increasingly critical. We did a deep dive into this topic, exploring alternative avenues of capital to finance this expenditure, in a collaborative report published a few days ago. The key takeaway from the report is that credit markets – secured, unsecured, and securitized in both public and private markets – will play a growing role in financing data centers.

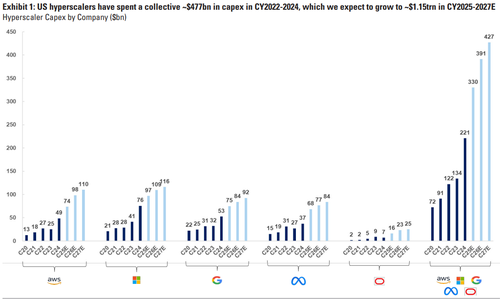

To be clear, capex related to AI and data centers has been in motion for the last few years. Spending from the hyperscalers alone has gone from ~$125 billion two years ago to ~$200 billion in 2024 and the consensus expectation is that it exceeds $300 billion in 2025.

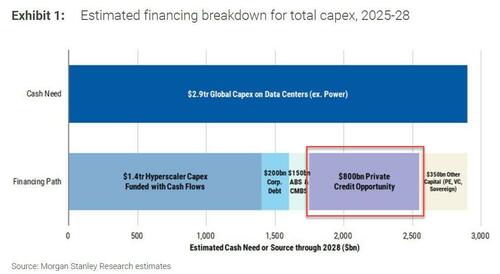

Internal operating cash flows from the hyperscalers have been the source of this spending. However, our equity analysts expect the investment needs for data centers to rise sharply over the next few years. While cash flows from hyperscalers will remain a key source of capital to finance data center-related spending, these alone will no longer be adequate, after accounting for cash build and shareholder capital returns. Leveraging our equity analysts’ projections, we estimate that $1.4 trillion of hyperscaler capex may be self-funded with cash flows, leaving a sizable $1.5 trillion financing gap.

We think that credit markets, broadly defined to encompass both public and private markets of different flavors, will gain traction as more efficient providers of capital to bridge this gap. There is a favorable alignment of significant and growing dry powder across credit markets with attractive real yields on offer with appeal to a sticky end-investor base (e.g., insurance, sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, endowments and high net worth retail) looking for scalable, high-quality asset exposures that can provide diversification benefits. We think that this alignment of needs of capital and investment will pave the way for bridging the $1.5 trillion financing gap.

We size the different financing channels as follows: unsecured corporate debt issuance from issuers in the technology sector (~$200 billion); securitized markets in the form of data center ABS and CMBS (~$150 billion), private credit markets in the form of asset-based financing (~$800 billion), and other capital sources across sovereign, private equity, venture capital, and bank lending (~$350 billion). Of these, we think that private capital – in particular credit – will play a key role in meeting a majority of the remaining financing gap as it sits optimally at the intersection of significant expansion in AUM in a higher rate environment and the complex, global, and customized financing needs that are associated with AI build-out.

As MS concludes, “the point we want to drive home is that credit markets will play a major role in enabling AI-driven technology diffusion” and of all the available sources of credit, the chart below shows just how big the debt hole is that private credit will have to plug.

Two months later, a study by Bain came to virtually the same conclusion:

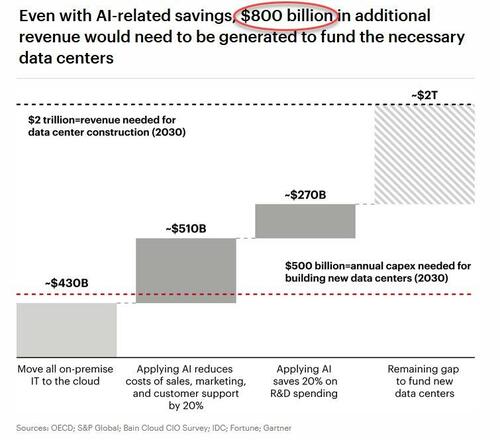

Bain’s research suggests that building the data centers with the computing power needed to meet that anticipated demand would require about $500 billion of capital investment each year, a staggering sum that far exceeds any anticipated or imagined government subsidies. This suggests that the private sector would need to generate enough new revenue to fund the power upgrade. How much is that? Bain’s analysis of sustainable ratios of capex to revenue for cloud service providers suggests that $500 billion of annual capex corresponds to $2 trillion in annual revenue.

What could fund this $2 trillion every year? If companies shifted all of their on-premise IT budgets to cloud and also reinvested the savings anticipated from applying AI in sales, marketing, customer support, and R&D (estimated at about 20% of those budgets) into capital spending on new data centers, the amount would still fall $800 billion short of the revenue needed to fund the full investment.

And visually:

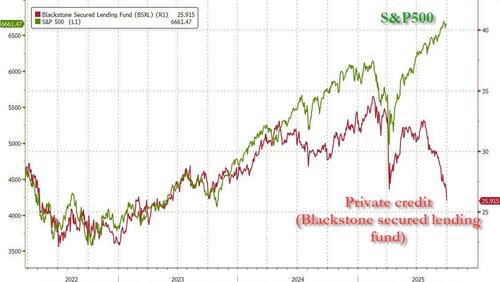

The problem, as we detailed last week, is that the private credit sector is starting to crack under the massive weight of its exposure to US consumers (where such notable implosions as the Tricolor and First Brands bankruptcies are just the beginning).

Luckily, there is also the public credit sector, and here we have a full-blown debt bubble brewing as well. And yes, it’s all tech related too.

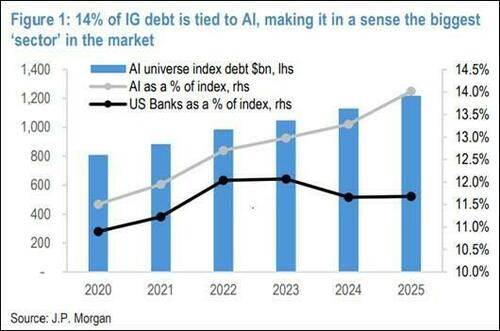

According to JPMorgan’s Eric Beinstein and Nate Rosenbaum (full note available here), AI-related companies now make up 14% of the Investment Grade Index with $1.2T in debt. Shockingly, this is now the largest sector within the IG index, exceeding Banks.

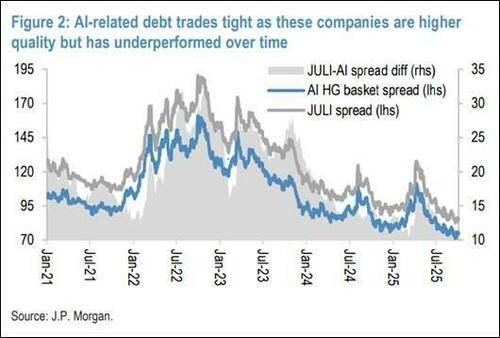

Further, the sector trades ~74bps which is 10bps tighter than the broader JULI index (these companies can be tracked on BBG via JPM’s Delta-One basket JPAMAIDE).

This is how Beinstein summarized the problem:

The torrid ascent of AI stocks has caused some angst for credit investors worried that any potential downside there could have credit implications. We think that from a fundamental perspective, these fears are not justified as these companies are either cash rich/not highly levered (Tech and Cap Goods) or highly regulated (Utilities). That said, an equity selloff in AI-related names would likely impact credit too, and, given these companies trade tight to the rest of the market, a short basket of single name CDS may be an effective tail-hedge for cross-asset investors.

In conjunction with JPM HG Credit Tech, Utilities and Cap Goods analysts, we have identified what we believe to be the current cohort of IG companies most closely tied to the AI revolution. The amount of debt tied to these companies has grown rapidly to $1.2tr currently. As such, AI companies as we define them now make up 14.0% of the IG index, which if thought of as a ‘sector’ is now larger than the largest HG sector (US Banks).

JPMorgan’s conclusion: “The market cap of the JPAMAIDE equity basket has grown to 39% of the market cap of the S&P500 so a repricing could be significant for broader markets“

At the single security level, AAPL, DUK, and ORCL are the largest bond issuers but are cash rich/net debt low types of companies. Of these, the last one is the most concerning because as JPM’s Cembalest wrote in “The Data Center Blob“, Oracle has a debt to equity ratio of 500% compared to 50% for Amazon, 30% for Microsoft and even less at Meta and Google. In other words, once the AI credit bubble bursts, Oracle will be the first to go.

There is a bigger problem: if and when the AI paradigm shifts, whether due to the market suddenly demanding tangible returns on AI investment and not just circle jerk funny money, or because China comes up with a 1000x cheaper AI chip than Nvidia, or reverse engineers a better LLM than anything the Sam Altman “non-profit” can push out, equity investors in the AI sector will suffer massive losses, but at least these will be large contained to the stock market. However, it is the AI credit, which is being used to pay for that $500 billion in annual capex and serves as the scaffolding of the broader economy, and which is “guaranteed” with future cash flows that will never come, that will be the true time bomb that wrecks the economy once the AI bubble bursts.

Or maybe not.

In its gloomy report (mentioned above), which calculated the massive funding shortfall facing the AI bubble and which virtually assures it will burst over time, the consultancy laid out a case in which the economics of AI might actually work:

Technological breakthroughs change the landscape. History is replete with unexpected leaps of progress in computational power. Sixty years of Moore’s law progress in semiconductors has given us handheld devices that far outperform the most powerful computers of the 1970s. Many speculate that quantum computing, for example, could displace the favored semiconductors trajectory of today, reducing the compute and power demands of tomorrow’s systems. Bain’s research suggests we are at least 10 to 15 years away from quantum computers stable enough to replace generative AI training and inference workloads. Other technological breakthroughs could include specially designed training and inference application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs), which could be more efficient than general purpose graphics processing units (GPUs), or new forms of memory or advanced packaging to improve power efficiency.

In other words, there is hope the AI bubble won’t burst and drag global markets and the economy with it, and that the AI sector will one day become self-sustaining. All we need, is a miracle.

More in the full JPMorgan notes here and here, available to pro subscribers.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 10/09/2025 – 10:12ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1