Creditors Of Bankrupt First Brands Say Billions “Simply Vanished” Amid Debt Rehypothecation Nightmare

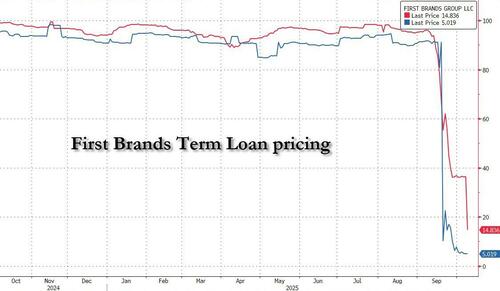

Hot on the heels of the spectacular implosion of subprime auto lender Tricolor (whose name is a not too subtle reference to the Mexican flag, and appropriately so as the company was almost exclusively targeting illegal aliens as its customers, so probably not a shock that it had a very unhappy ending), last month’s mega bankruptcy was that of First Brands, an auto parts supplier with $5.8 billion in outstanding leveraged loan debt, yet it increasingly appears the company had far more liabilities than previously known as a result of what now learn learn, was extensive rehypothecation of said debt, a practice traditionally associated with such unregulated banana republics as China (who can possibly forget the country’s copper rehypothecation scandal a decade ago). Adding to the complexity of this blistering meltdown, which has seen the company’s debt trade from par to the teens in hours…

…. the debt isn’t merely good old-fashioned debt, but is also off-balance sheet debt, such as receivables and inventory financing, where private credit funds (one reason why such funds as the Blackstone BDC and Blue Owl are scraping multi year lows) provided much of this financing.

The outcome is surreal nightmare where nobody knows who owns what, or where the money – what little is left of it – actually is.

As the WSJ first reported last week, and as perpetual B-grade investment bank Jefferies – which has emerged as the main loser so far in the First Brands drama – confirmed today, the company’s advisers are now “investigating whether receivables may have been pledged as collateral more than once.“

In other words, not only was the company neck-deep in debt, it also used off-balance sheet debt such as receivables factoring (i.e., debt collateralized by accounts receivable) to push its total debt load well beyond its neck.

As a result, the First Brands bankruptcy – which listed liabilities between $10 billion and $50 billion, and assets between $1 billion and $10 billion, according to its Sept. 28 filing in the Southern District of Texas – is unlike anything we have seen in years, and which has been kept away from the front pages simply because of all the idiocy taking place daily in the AI bubble which has so far managed to distract the broader population away from, well, everything else.

So what is taking place? Quite a few things it appears… and we don’t really know the full answer as we learn more details about fallout every the day. What we do know so far is that some of the most “sophisticated” players on Wall Street have lost hundreds of millions in the bankruptcy, among them:

- UBS O’Connor: the once iconic hedge fund associated with the only major Swiss bank left standing after the Credit Suisse collapse, has 30% of its portfolio tied to First Brands, leaving Switzerland’s largest bank grappling with a bankruptcy that has convulsed global finance. Overall, UBS has more than $500mn of exposure to First Brands’ debt and invoice-linked financing, across various parts of its investment arm.

- As the FT reported, “clients are braced for big losses after UBS O’Connor, a private credit and commodities specialist owned by the Swiss bank, revealed that 30 per cent of the exposure in one of its funds is tied to the auto parts group.”

- O’Connor recently told investors in its “Opportunistic” working capital finance strategy that the fund had 9.1% of “direct” exposure, financing facilities based on invoices First Brands’ was due to pay, and 21.4% of “indirect” exposure, based on invoices its customers were due to pay (source FT).

- Millennium Management: one of the world’s largest multistrat hedge funds, which manages $80BN , has also gotten hit by the sudden unraveling of the auto-parts supplier First Brands Group. An investing team at Millennium led by Sean O’Sullivan took a writedown on a First Brands bet as the supplier slid toward bankruptcy, according to people with knowledge of the matter. The loss is expected to total about $100 million

- Millennium’s losses are tied to short-term loans that it offered First Brands to finance its inventory. The company made extensive use of a practice known as factoring, which allowed it to borrow against current cash flows. Some 70% of the auto supplier’s revenues were channeled through factoring (source BBG).

- Millennium’s losses are tied to short-term loans that it offered First Brands to finance its inventory. The company made extensive use of a practice known as factoring, which allowed it to borrow against current cash flows. Some 70% of the auto supplier’s revenues were channeled through factoring (source BBG).

- Onset Financial: the Draper, Utah-based company describes itself as a “dominant force and leader in the equipment lease and finance industry” and had built up $1.9bn of exposure to First Brands in the years before it collapsed into bankruptcy, according to legal filings. This makes the specialist company the biggest known creditor to First Brands, which has now disclosed that it built up almost $12bn in debt and off-balance sheet financing. Onset’s exposure eclipses some of the biggest names on Wall Street, which are facing the prospect of multibillion-dollar losses in a chaotic bankruptcy process.

- Onset last Tuesday filed a “preliminary objection” to a $1.1bn “debtor-in-possession” (DIP) loan that First Brands has agreed with other creditors. This first-ranking loan is intended to provide the Ohio-based car parts group with emergency funding. In its filing in the Southern District of Texas bankruptcy court, the Utah-based company’s lawyers wrote that “First Brands owes Onset approximately $1.9bn” and that the relationship between the private finance firm and the car parts company “dates back to 2017”. “When the dust settles, this court will see that Onset was the single most significant provider of liquidity to the debtors,” Onset’s lawyers wrote (source FT)

- Onset last Tuesday filed a “preliminary objection” to a $1.1bn “debtor-in-possession” (DIP) loan that First Brands has agreed with other creditors. This first-ranking loan is intended to provide the Ohio-based car parts group with emergency funding. In its filing in the Southern District of Texas bankruptcy court, the Utah-based company’s lawyers wrote that “First Brands owes Onset approximately $1.9bn” and that the relationship between the private finance firm and the car parts company “dates back to 2017”. “When the dust settles, this court will see that Onset was the single most significant provider of liquidity to the debtors,” Onset’s lawyers wrote (source FT)

- CLOs: Collateralised loan obligations, structured investment vehicles that have long bolstered the market for lending to riskier companies, were among the holders of First Brands’ loans. While this debt was private, it was “broadly syndicated” in a process overseen by banks, rather than negotiated directly between the funds and the company. CLOs report their holdings publicly and typically require credit ratings for the loans they buy.

- CLOs bought First Brands debt at close to par but even its first-ranking debt is now trading around 15 cents on the dollar. Big holders of First Brands debt through these vehicles and other loan funds have included asset managers PGIM, CIFC and Blackstone (Source FT).

- CLOs bought First Brands debt at close to par but even its first-ranking debt is now trading around 15 cents on the dollar. Big holders of First Brands debt through these vehicles and other loan funds have included asset managers PGIM, CIFC and Blackstone (Source FT).

- Private Credit Funds. CLOs were not enough for the First Brands shady management team: the company engaged in even more under-the-radar financing. It was a big user of invoice and inventory finance, much of which is less clearly disclosed on corporate balance sheets. Private credit funds provided much of this financing.

- While First Brands’ accounts did not clearly disclose how much it had outstanding in “factoring” facilities, which allow companies to sell outstanding customer invoices to banks or investors in return for upfront cash, the group recently gave more detail to potential lenders. This showed it had $2.3bn of “factored” customer invoices — expected inflows of funds that it has sold to lenders in exchange for cash — outstanding at the end of 2024. This was equivalent to more than 70% of its annual sales (Source FT).

- First Brands’ accounts show it also had $682mn in “supply chain finance” outstanding at the end of 2024, a technique sometimes called “reverse factoring” under which a lender pays suppliers’ bills upfront and then collects the money from the company later.

- First Brands had also raised inventory finance, typically secured against stock in warehouses, through several “special purpose entities”. Specialist credit investment firms Evolution Credit Partners, AB CarVal and Aequum Capital are named in relation to the inventory debt in Sunday’s bankruptcy petition. Boston-based Evolution is separately listed as having factoring exposure.

Which is not to say that everyone lost money: two clear winners, who shorted First Brands debt, have emerged:

- Apollo, which we learned last month had built a short position against the company’s debt, something that is difficult and expensive to do for both technical and administrative reasons. Apollo held the short for more than a year, although it had closed the position before the bankruptcy. In the context of Apollo’s $840bn of assets, any windfall on the First Brands short is likely to be small. However, the bet could still draw further scrutiny given the firm’s private equity funds own Michigan-based auto parts maker Tenneco, a rival to First Brands.

- Diameter Capital Partners: a US credit hedge fund in which Apollo holds a stake, also shorted the debt and took profits on the trade recently. Diameter is known for its buccaneering bets in credit markets, having been an early buyer on long “hung” loans linked to Elon Musk’s buyout of Twitter.

But the biggest hit from the First Brands debacle so far, is that of perpetual bulge bracket wannabe investment bank Jefferies.

Jefferies, best known for long being one of the hardest-charging banks on Wall Street in the niche area of issuing riskier debt to bond and loan investors (it specializes in the B2/B-rated middle market, and used to be one of Donald Trump’s staple banks during his Atlantic City casino period, when no other bank would touch him). has grown its business prolifically since the financial crisis, hiring from rivals and expanding its business with private equity sponsors but its reputation in US credit markets had already suffered from its decision to lead a junk bond deal for struggling department store group Saks Global in December. Less than a year after issuance, the company restructured its debt, pitting creditors against each other. Some of its bonds are trading at less than 40 cents on the dollar, with investors suffering painful paper losses.

Now, as the FT reports, the First Brands fiasco threatens to tarnish its image further. Jefferies’ relationship with First Brands stretches back years, with SEC filings showing it financed multiple transactions for the group when it was growing fast. The wheels came off its latest debt deal, a $6bn loan intended to refinance the group’s debt stack, last month after debt investors requested more information about First Brands’ invoice factoring and other elements of its accounting.

Jefferies promptly shelved the deal, framing it as a pause until clarity was reached, but First Brands instead collapsed into bankruptcy within weeks.

But crushing its clients was just the start: the banking group also had more direct exposure to the multibillion-dollar bankruptcy. Many of First Brands’ loan investors were not aware that an investment unit of Jefferies also provided more opaque financing to the auto parts company linked to its customer invoices. An FT report revealed the connection this month. Jefferies, along with three other creditors to First Brands’ invoice “factoring” facilities, is listed as an unsecured creditor with a “contingent”, “unliquidated” or “disputed” claim, indicating its claim could face difficulties.

As a result, Bloomberg reports that for Jefferies – First Brands’ banker for more than a decade – the speculation around its role in the sudden demise of First Brands has became too loud to ignore, and the bank has come under scrutiny for its relationship with First Brands and its spectacular collapse.

On Wednesday, Jefferies sought to clear the air, laying out in the most direct terms yet how it is, and isn’t, exposed to potential losses tied to First Brands. The pain point for Jefferies, along with other financial firms, is Point Bonita Capital. That fund has about $715 million invested in invoices due by First Brands’ customers including Walmart and AutoZone, with the auto-parts supplier responsible for directing payments to Point Bonita. That’s about a quarter of its $3 billion trade finance portfolio.

Jefferies’ Leucadia Asset Management has a $113 million equity stake in Point Bonita, the bank said. And while Jefferies’ potential losses tied to the saga seem likely to be manageable – Morgan Stanley analysts earlier on Wednesday put them at a maximum of nearly $45 million – new details on the collapse keep coming to light.

The bank’s relationship with First Brands started around 2014, when it stitched together a loan to its predecessor company, Crowne Group. First Brands then grew through debt-funded acquisitions of autoparts sold through retailers like Walmart and O’Reilly Auto Parts, tapping the leveraged loan market along the way.

Over the years, First Brands increased its use of trade finance, an opaque but relatively common type of financing that sits off-balance sheet and has been hit by frauds in recent years. At times, it used this to raise money that would otherwise have breached rules on the existing loans, loans that Jefferies helped arrange.

In one such instance, Bloomberg reports that First Brands set up a so-called side letter agreement with Point Bonita for an additional trade financing facility. The agreement enabled First Brands to raise funds at an interest rate above the limits permitted by its existing loan documents — because it instead paid the fund a “supplemental incentive fee” in addition to that rate.

More recently in July, Jefferies was pitching investors on a roughly $6 billion refinancing deal for First Brands. But, as noted above, lenders in that debt began raising concerns over the company’s use of trade financing. Their concerns prompted the pause of the refinancing effort in August and the decade-long relationship suddenly appeared on less solid ground: Jefferies struggled to get information from the company, it told investors. The reality: it didn’t want investor to realize that the company was insolvent.

First Brands filed for bankruptcy just weeks later, in late September.

“The reputation risk is a big hit, because clients are potentially losing significant amounts of money,” Sean Dunlop, an analyst at Morningstar, said in an interview, noting how Jefferies is known as a hard-charging bank that arranges debt for some of the market’s riskiest borrowers. “This fallout is the ramification you see from that, from time to time.” He added that clients hit by the First Brands incident are less likely turn to Jefferies when they need to raise capital quickly, or participate in future deals more broadly.

“I would look at it as potentially damaging the pipeline of investment banking business and asset management inflows,” he said.

Sure enough, Bloomberg reports that BlackRock has requested to pull some money it invested in the abovementioned Jefferies fund Point Bonita Capital, which is a unit of Jefferies’ Leucadia Asset Management, and has a $3 billion trade-finance portfolio. Since 2019, Point Bonita’s portfolio has included accounts receivables tied to First Brands. The partial redemption requests were made in September as the financial situation of the auto-parts supplier worsened.

On Wednesday, Jefferies said that Point Bonita had $715 million invested in receivables owed to First Brands. While that means the fund is exposed to the credit risk of its customers, including Walmart and AutoZone, First Brands was responsible for directing payments to Point Bonita. Those payments stopped on Sept. 15, almost two weeks before the company filed for bankruptcy. First Brands’ special advisers are now investigating whether receivables may have been pledged as collateral more than once, Jefferies said in the statement.

* * *

So what do we know so far: the list of names involved in the bankruptcy, either as advisors or investors (on both the long and short side) is a vertiable who is who of Wall Street icons (and wannabe icons). And while Jefferies appears to have pulled yet another soft con job (not that shocking for a firm whose core junk bond bankers and traders, not to mention its CEO, came out of Drexel), it did so with financial sophisticated counterparts, so it will be nearly impossible to assing blame for the massive losses that will be in the billions.

The bigger question is what is the systemic fallout from this spectacular implosion.

Here, the biggest issue by far is the realization that with markets at all time high, not only are supposedly solvent and viable companies barely worth pennies on the dollar (when the full picture is finally produced), but that as a result of operational opacity – and potential fraud – nobody actually knows where the money has gone.

Charles Moore, a managing director at Alvarez & Marsal who is acting as First Brands’ chief restructuring officer, has said that an investigation into the car parts group’s off-balance sheet financing is examining whether collateral underpinning its financing was pledged “more than once” and “commingled” between lenders.

In other words, debt collateralized by the same assets multiple times. Sorry, we forgot to add: worthless assets.

At a court hearing last Wednesday to decide whether to release the continue funding the bankruptcy entity, the judge overseeing the bankruptcy approved the Dip loan, while making clear that the loan needed stipulations because of concerns from the group and other asset-backed lenders.

“It is clear that this debtor needs [ . . .] an incredible amount of financing,” Judge Christopher Lopez said. “I don’t think since my time on the bench I’ve seen anything like this.”

One week later, Jefferies – which was the company’s banker – said that it was only now investigating whether receivables may have been pledged as collateral more than once.

The answer is yes: Raistone, a provider of short-term financing that worked on deals for First Brands Group, is demanding the appointment of an independent examiner for the business after alleging late Wednesday that as much as $2.3 billion has “simply vanished” from the bankrupt auto-parts supplier.

The request for appointment of an independent examiner follows an Oct. 2 email exchange in which a bankruptcy lawyer for First Brands told Raistone that advisers don’t know if the auto parts supplier has received an estimated $1.9 billion. The exchange followed First Brands’ initial court hearing in which the company won access to more than $1 billion in emergency financing to prevent the business from collapsing.

“First, do we know whether FBG actually received $1.9 billion (no matter what happened to it)?,” Raistone lawyer Emanuel Grillo said in an Oct. 2 email, which was filed in bankruptcy court in support of its request for an examiner. “Second, would you tell us how much is in the segregated accounts in respect of the factored receivables as of today?”

“#1 —We don’t know,” First Brands restructuring lawyer Sunny Singh said in response to the questions. “#2 – $0.”

Raistone said Wednesday that the board investigation “is woefully insufficient given the magnitude of potential misconduct at issue.”

It is indeed, and unfortunately, this is just the start, and once the public euphoria with the AI bubble – which is soaking up all attention like the world’s biggest mushroom – finally fades, watch out below as Second, Third, Fourth and so on instance of First Brands, shows just how hollow the current market all time high truly is.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 10/09/2025 – 01:10ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1