‘Disruptions Come First, Benefits Take Time’: Fed Warns Of AI’s Imminent Impact On Job Market

Earlier, Richmond Fed President Thomas Barkin told an audience at the Aiken Chamber of Commerce in South Carolina that consumers “are still spending … we’re not in 2022 anymore. Consumers aren’t as flush,” while also discussing artificial intelligence trends in the labor market.

“While consumers are still spending, we are not in 2022 anymore. Consumers are not as flush. They are making choices,” Barkin said, adding that demand remains strong among higher-income earners.

Barkin then discussed AI trends reshaping the job market, noting that adoption is ramping up across call centers and in coding roles. He observed a noticeable shift in hiring dynamics, with executives reporting a surge in applicants for every open position.

UBS analyst Nana Antiedu was keeping track of Barkin’s comments earlier…

Barkin’s comments come just one day after the Federal Reserve’s Beige Book was released, which appeared rather uneventful at first glance. However, one section deserves attention (read here). Here’s an excerpt from our note yesterday:

In labor markets, the picture remains one of muted stability and rising wages (thanks to the collapse of labor supply from illegal aliens). One notable change was the discussion of Artificial Intelligence as potentially taking away from labor demand. Oh, just wait: it’s only starting… and it ends with Universal Basic Income. Here are the details:

- In most Districts, more employers reported lowering head counts through layoffs and attrition, with contacts citing weaker demand, elevated economic uncertainty, and, in some cases, increased investment in artificial intelligence technologies.

Also yesterday, Fed Governor Christopher Waller addressed the long-standing debate over whether new technologies destroy or create jobs in Arlington at the DC Fintech Week…

Whenever a new technology emerges, the first question economists get is about jobs: Will this replace people or make them more productive? The challenge is that, with innovation, there is often a time inconsistency between the costs and the benefits. The disruptions come first; the benefits take time. When a new technology appears, it’s always easier to see the jobs that are likely to disappear, but it’s much harder to see the ones that will be created. When automobiles came on the scene, it was easy to see that saddlemakers’ jobs would disappear. But it wasn’t obvious that the saddlemaker’s skills could be used to make car seats and that higher-productivity auto production would create many more and much higher-paying jobs. Ten years ago, if I had said something called TikTok would arrive soon, no one would likely have been able to imagine that, or that social media would create what is now an established occupation—influencer.

The pattern appears to be repeating—only faster. A recent study by Stanford economists found that employment has fallen about 13 percent in occupations most exposed to AI, relative to those less affected. Those contractions have appeared mainly in support and administrative roles—fields that tend to be automated first. This early effect from AI is consistent with what I have been hearing from business contacts. Retailers in particular are cutting back on employment for call centers and IT-related occupations. So far, most say this is being handled through attrition, but a number of retailers say that there is the potential for downsizing next year. That is also a message from a New York Fed survey that finds very few businesses are reporting AI-induced layoffs; they are instead using the technology to retrain employees. That said, AI is influencing recruiting for these firms, with some scaling back hiring because of AI and others adding workers who are proficient in its use. Looking ahead, however, layoffs and reductions in hiring plans due to AI use are expected to increase, especially for workers with a college degree.

Returning to my final point, history has shown us that technology improves productivity and our standard of living. We initially always talk about how it will be a substitute for labor. This was the basic premise behind Marx’s theory of capitalism—machines would replace humans in production, which would raise unemployment so high that social revolution would occur, leading to the end of capitalism and the rise of a socialist utopia. Yet this theory makes the fundamental mistake of failing to see that capital and labor are complements, not substitutes. More machines mean a firm can produce more output, but that also requires more labor as well. This is obvious just looking at economic data. The U.S. capital stock, measured in constant prices, is seven times larger than it was in 1950. Yet the unemployment rate in September 1950 was 4.4 percent, and it is 4.3 percent as of August 2025. This is why economists are typically techno-optimists—history has repeatedly shown that adopting new technologies leads to economic growth and greater employment, not less. Technological disruption is one form of a concept that economists have studied since Joseph Schumpeter named it in 1942: creative destruction. This topic has never been more relevant, and I note that just last week a share of the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to two economists who explored how productivity-enhancing disruption raises living standards

There will surely be losers and winners from AI, but aside from questions about how AI’s gains will be distributed, there is the more fundamental matter of how they will be measured, even at a macro level. Firms are using AI to increase productivity, which allows for greater output based on the same level of inputs. This gain is counted in gross domestic product (GDP) and its corollary, gross national income.

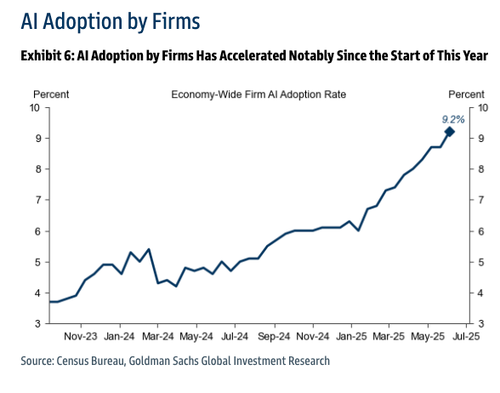

In America, one common feature of great technological innovations has been an onslaught of competition that has rapidly driven down costs and resulted in rapid and widespread adoption. If hardware and software innovation continue to drive down the cost of AI, then I see few barriers to its ongoing proliferation throughout the economy. That prospect, clearly, is driving the surge of AI investment we have seen. Will it continue? That will depend, in part, on whether AI delivers on the productivity increases that some believe it will bring.

Building on a recent Goldman report, the current adoption rate stands at roughly 9.2% economywide. Skeptics like Elliott Management have called this AI cycle “overhyped.”

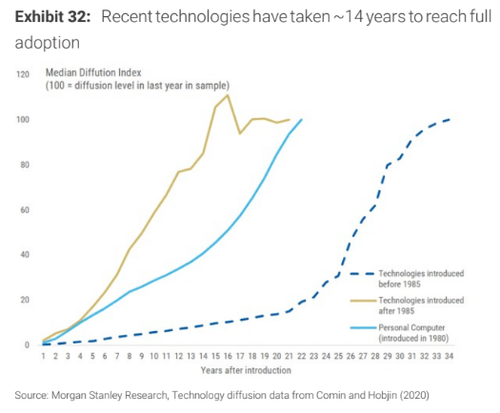

However, a team of Morgan Stanley analysts recently told clients that “AI impacts may take longer to appear in economic data,” with the first real signs not expected until “later this decade and into the next.”

“While AI adoption may be faster than past technologies, we think it is still too early to see it in economic data, outside of business investment,” Stephen Byrd told clients.

What’s evident is that the early signs of AI job displacement are underway. We’ve done the hard work to figure out this trend with more details found here:

-

200,000 Wall Street Jobs At Risk As “Agentic” AI Becomes “Major Breakthrough”

-

Billions Spent On Data Centers – But Where Is The AI Adoption Rate?

Fund UBI stimmies with tariffs?

Tyler Durden

Thu, 10/16/2025 – 17:20ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1