This video is available on Rumble, Bitchute, Odysee, Telegram, and X.

St. Paul’s Cathedral is one of the most glorious buildings in London. I was dazzled by it.

To step inside is to be even more awed than to see it in the distance. There is magnificence everywhere — this is the choir — and the dome, which towers 365 feet above the cathedral floor, is the tallest in Britain.

I climbed the 528 steps to the top for this marvelous view, with the London Eye on the horizon.

The greatest British architect, Sir Christopher Wren, laid St. Paul’s foundation stone in 1675, and declared the cathedral finished in 1711.

It is filled with beautiful monuments to British military might and imperial grandeur. And today’s Brits are deeply ashamed of this. As Church Times, an Anglican magazine, says about church sculpture, “Many very fine monuments memorialise thoroughly evil men.”

There are a few statues of people who weren’t soldiers or colonial governors.

This is the painter, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and here is the literary figure, Samuel Johnson, with an inscription in Latin, of course.

But St. Paul’s is The Church Militant, dedicated to empire and military might. I’m sure vast congregations sang “Onward Christian Soldiers,” now banned from many hymnbooks.

To atone for this, the cathedral invites you to “Explore the trail,” that is, the trail of rapine and exploitation these famous men trod.

The cathedral asked non-whites — always non-whites — to tell us about some of the empire-builders.

For example, here is a beautiful monument to General Charles Cornwallis. Americans think he disappeared after George Washington defeated him at the Battle of Yorktown, but he is honored here as Governor of Bengal.

The cathedral asked a Bengali to explain how his rule led to “the widespread impoverishment of the peoples and communities ruled by the East India Company.” Cornwallis made India so miserably unlivable that it “result[ed] in the South Asian diaspora communities in both the UK and around the world today.”

It’s because of Cornwallis’s wretched misrule that there are so many Indians in Britain and Canada and the United States.

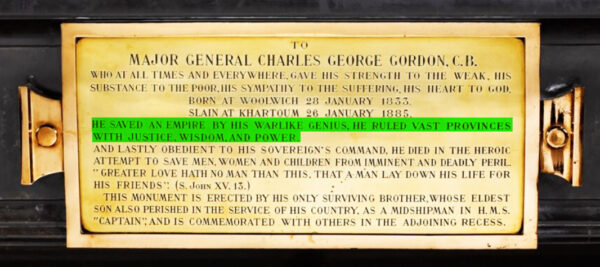

General Charles George Gordon has a lovely cenotaph, but he was as bad as Cornwallis.

Here are some details of the monument, including Gordon’s hand, resting on a Bible.

Here is Gordon ministering to young Sudanese boys at a school he set up in Khartoum.

The brass plaque on the sarcophagus says, “He saved an empire by his warlike genius. He ruled vast provinces with justice, wisdom, and power.”

It was the Ching Dynasty that he saved from the Taiping Rebellion. Someone named Amrita Shodham explains that his career “show[s] how the British propped up compliant — but deeply unpopular — regimes in colonial locations.”

His policies in India led to “widespread impoverishment of Indian peasants” and “contributed to large labour flows out of India.”

Just like Cornwallis.

The Duke of Wellington, victor of Waterloo, has a spectacular tomb, but it is undeserved, because he also consolidated military control of India.

Abdul Sabur Kidwai explains that because of his rapaciousness, “one country became the ruler of almost a quarter of the world, and set up an inherently unequal world system.”

Field Marshal Robert Napier was commander in chief in India for six years.

He led the famous Expedition to Abyssinia, which was one of the most remarkable imperialist undertakings in the history of empire.

You should look it up.

Bengali Taryn Khanam explains what Napier was really up to: “economic exploitation, territorial annexations, displacement of Indian rulers and chiefs, and discrimination against Indian soldiers.”

General Charles Napier, a distant relative, conquered Sindh, in what is now Pakistan.

He defeated an army of 30,000 with just 2,800 men, and after the Battle of Sindh, he telegraphed the famous one-word dispatch: Peccavi, which is Latin for “I have sinned (Sindh).”

Asif Shakoor goes on at great length about how brutal the British were, but the worst thing he has to say about Charles Napier is that “he hoped to ‘catch the rupees,’ that is, make money for his daughters.”

This imposing monument is to Sir Henry Bartle Edward Frere.

Sanchita Mukherjee explains that Frere was called “a ‘violent conqueror of African peoples’ and ‘the Empire’s leading warmonger, and is remembered as the man who started the Zulu War that led to the deaths of tens of thousands of African people.”

An unsigned diatribe against General Thomas Picton, the highest ranking British officer killed at Waterloo, highlights his rule in Trinidad:

“His governance was characterised by cruel and oppressive methods: Picton maintained order through torture and dozens of executions designed to scare all the inhabitants.” We are told he was known as the “Tyrant of Trinidad.”

Richard Southwell Bourke was the fourth Viceroy of India, and Niaz Alam explains that he kept Indians illiterate, and suspects that “many famines in India were worsened or even caused by colonial rule.”

Major General Charles MacGregor was an explorer and intelligence officer, and his monument says he was “undaunted by difficulties, courting danger, loving responsibility. As an officer, a leader, an explorer, unsurpassed. A good son, an affectionate husband, a loving father, he became a great example of what a soldier should be.”

Mian Obaid Shah says he was a murderer and a terrible man, and that “the East India Company’s actions [were] grossly unjust and akin to banditry.”

And so it goes.

The cathedral notes that for every one of these smears, the “text is available in Bengali, Gujurati, Urdu, Hindi, Punjabi, and Tamil.”

Clearly, as we stand before these heroes, we’re supposed to think, “What beasts the British were to build monuments to such vicious men.” The more glorious the achievements of the past, the more cravenly we must grovel.

St. Paul’s scorns even the Christian faith these men professed: “the official commemoration of national figures in St Paul’s keeps in perfect step with the country’s imperial expansion, with absolutely no suggestion that the occupation of these countries in any way conflicted with the workings of God’s will.”

The top dog at the cathedral, the Bishop of London, must know God’s will. Well, here she is, Dame Sarah Mullally.

Credit Image: © Rob Pinney/London News Pictures via ZUMA Wire

Surely, she knows the Lord’s purposes better than any of those centuries’ worth of men who put up those vile monuments.

Credit Image: © Jonathan Brady/PA Wire via ZUMA Press

No doubt it’s God’s will that Britain, which used to rule the waves, should sink beneath a rising tide of color.

Credit Image: © Mark Thomas/i-Images via ZUMA Press

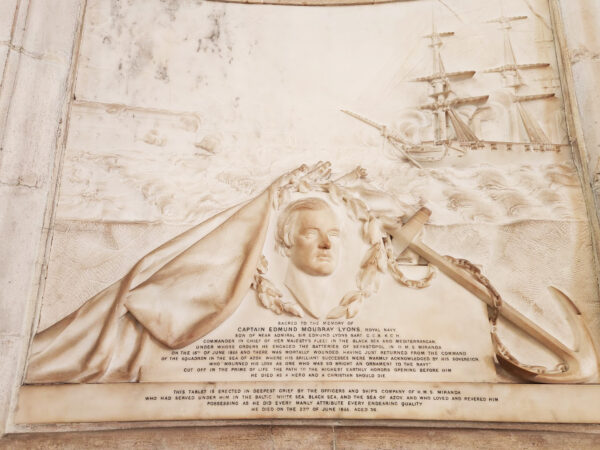

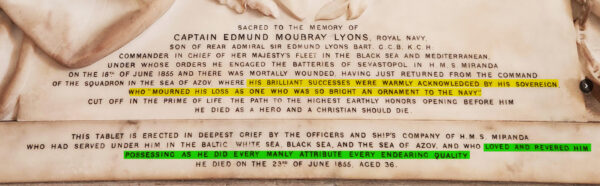

I’ll end with a monument to a man from a better time. I’m sure he would hardly believe his eyes if he were to see London today. He was Captain Edmund Lyon, killed in action in 1855, age just 36.

His memorial is modest, but the inscription contains these lines.

“His brilliant successes were warmly acknowledged by his sovereign” — that would be Queen Victoria — who “mourned his loss as one who was so bright an ornament to the navy.” His officers and men “loved and revered him, possessing as he did every manly attribute, every endearing quality.”

Every manly attribute, every endearing quality. Anyone who apologizes for the past greatness of his people hardly knows what those words even mean.

The post St. Paul’s Cathedral: From Glorious to Groveling appeared first on American Renaissance.

American Renaissance

R1

R1

T1

T1