The Psychology Of Investing In A Zero-Risk Illusion

Authored by Lance Roberts via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

Every market cycle eventually changes investor psychology to believe risk has been conquered. The storylines may change, from “this time it’s different” to “the Fed has our back,” but the psychology does not. When markets rise steadily and volatility remains low, investors confuse stability with safety. That’s precisely the illusion forming in markets today. The S&P 500’s relentless climb, paired with suppressed volatility and ample liquidity, has given the impression that downside risk has somehow been engineered out of the system.

This is where the trap begins. Behavioral finance tells us that people respond more to “how” risk feels than to what the data shows. When investors no longer feel anxious, they begin to take risks they wouldn’t otherwise tolerate. Rising prices reinforce optimism, optimism drives more buying, and the cycle continues until the most minor shock shatters the illusion. Low volatility environments create the psychology for instability by suppressing the healthy corrections that usually reset investor expectations. The longer the calm lasts, the more fragile the market becomes beneath the surface.

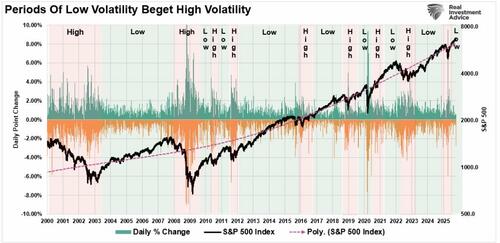

“Hyman Minsky argued that financial markets have inherent instability. As we saw in 2020-2021, asymmetric risks rise in market speculation during an abnormally long bullish cycle. That speculation eventually results in market instability and collapse. We can visualize these periods of ‘instability’ by examining the daily price swings of the S&P 500 index. Note that long periods of “stability” with regularity lead to “instability.”

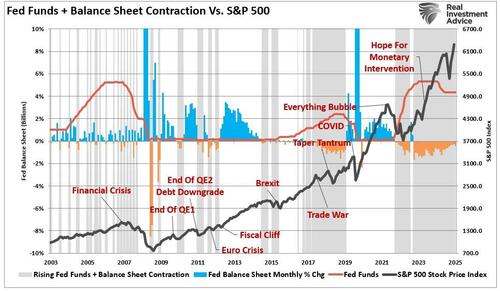

The illusion of safety doesn’t just emerge spontaneously; it’s nurtured by central bank policy. For nearly fifteen years, the Federal Reserve has acted as a stabilizer of last resort, flooding the system with liquidity at the first sign of stress.

Even though the Federal Reserve has withdrawn that monetary support, investors still believe that the Fed can and will always prevent pain. Over the last three years, investors have shifted their focus away from fundamentals and to each “Fed Meeting” for clues as to when the subsequent monetary intervention will arrive.

That shift in psychology is crucially important to understand.

The Fed and the Mirage of Control

The belief that the Federal Reserve can always come to the rescue carries its own danger: it encourages behavior that assumes the absence of consequence. Markets built on faith rather than fundamentals are inherently unstable, no matter how calm they appear.

The Federal Reserve’s well-intentioned interventions have created one of modern finance’s most powerful behavioral distortions: the conviction that there is always a safety net. After the Global Financial Crisis, zero interest rates and repeated rounds of quantitative easing conditioned investors to expect that policy support would always return during volatility. Over time, that conditioning hardened into a reflex: buy every dip, because the Fed will not allow markets to fail.

This is the concept of “moral hazard” in action.

What exactly is the definition of “moral hazard?”

Noun – ECONOMICS: The lack of incentive to guard against risk where one is protected from its consequences, e.g., by insurance.

A good example of this is shown below.

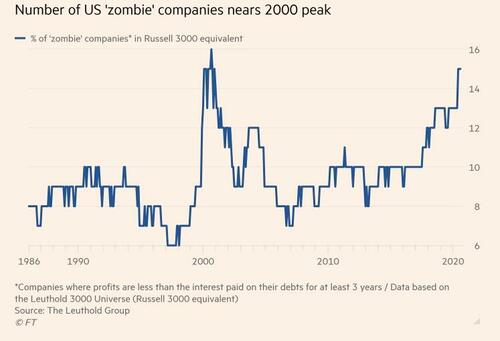

For their survival, zombie companies depend on a speculative investment climate for bond issuance. As discussed in “Recessions Are A Good Thing:”

“‘Zombies’ are firms whose debt servicing costs are higher than their profits but are kept alive by relentless borrowing. Such is a macroeconomic problem. Zombie firms are less productive, and their existence lowers investment in, and employment at, more productive firms. In short, a side effect of central banks keeping rates low for a long time is it keeps unproductive firms alive. Ultimately, that lowers the long-run growth rate of the economy.” – Axios

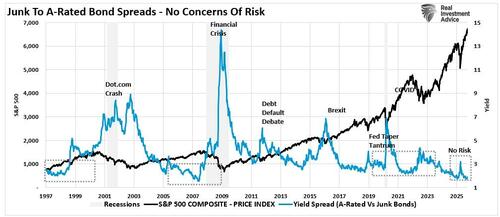

We also see the same “moral hazard” in the spread between “junk bonds” and A-rated corporates. At a spread of just 1.9%, investors are not being “paid” for the default risk they take with “junk bonds.” The only reason those spreads exist is that investors believe, with almost absolute certainty, that companies will pay their obligations, if not on their own, then with the help of the Federal Reserve.

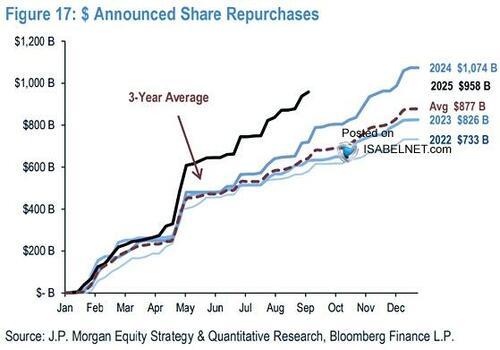

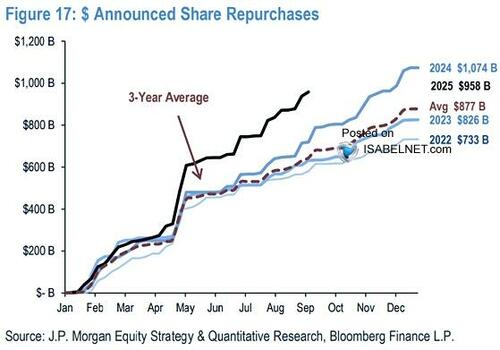

This mindset has reshaped corporate behavior as well. Companies, confident that credit will remain cheap and plentiful, used debt not to invest productively but to repurchase their shares, shrinking equity floats and boosting earnings per share. This financial engineering, which is currently running at a record pace, helps drive valuations higher, reinforcing the illusion that fundamentals were improving. In reality, liquidity is doing the heavy lifting. The absence of meaningful corrections gave investors an unbroken string of positive reinforcement, a psychological loop that made risk feel optional.

Liquidity, however, is not the same as stability. It masks fragility the way calm seas hide strong undercurrents. When liquidity recedes, even modest disruptions can become magnified. Consider 2018’s “Volmageddon,” when volatility-shorting strategies that had profited for years imploded in a single session. Investors mistook a quiet market for safety, believing their models had tamed uncertainty. In truth, they had only suppressed it.

That lesson is timeless: every era’s innovation eventually finds its limit when liquidity dries up and the illusion of control vanishes.

Behavioral Biases and the Return of Fear

If the Fed and liquidity conditions create the structure of the zero-risk illusion, human psychology provides its fuel. The psychology of investing, in particular, explains why investors underestimate danger when markets are calm. However, psychology is the most significant reason for underperformance by investors who participate in the financial markets over time. Behavioral biases leading to poor investment decision-making are the greatest contributor to underperformance over time. Dalbar defined nine of the irrational investment behavior biases specifically:

-

Loss Aversion: The fear of loss leads to a withdrawal of capital at the worst possible time. Also known as “panic selling.”

-

Narrow Framing: Making decisions about on part of the portfolio without considering the effects on the total.

-

Anchoring: The process of remaining focused on previous events and not adapting to a changing market.

-

Mental Accounting: Separating the performance of investments mentally to justify success and failure.

-

Lack of Diversification: Believing a portfolio is diversified when it is a highly correlated pool of assets.

-

Herding: Following what everyone else is doing. Leads to “buy high/sell low.”

-

Regret: Not performing a necessary action due to regret over a previous failure.

-

Media Response: The media is biased towards optimism to sell products from advertisers and attract viewers/readership.

-

Optimism: Overly optimistic assumptions lead to rather dramatic reversions when met with reality.

Recency bias also leads us to project the recent past into the future. When markets rise for months, we instinctively assume they will keep doing so. The longer an uptrend persists, the more investors become anchored to it emotionally, treating it as the new normal. Confirmation bias then compounds the problem. Bullish investors seek information that validates their optimism and dismiss data that challenges it. Financial media and social networks amplify this echo chamber, drowning out contrarian voices. Finally, reverse loss aversion, a flip of the classic behavioral rule, takes hold. When portfolios swell, investors become less sensitive to risk because the pain of potential loss feels abstract compared to the pleasure of ongoing gains.

As shown in the chart below, this behavioral trend contradicts the “buy low/sell high” investment rule.

These psychological patterns explain why market collapses often appear to come “out of nowhere.” In truth, the seeds of every downturn are sown during the good times, when caution fades and discipline erodes. A lack of volatility anesthetizes investors, dulling their instinct to manage risk. When the inevitable reversal comes, it is not just unprepared portfolios but mindsets that suffer. The speed with which optimism turns to panic reflects how thoroughly investors have internalized the belief that markets cannot fall.

In the end, we are just human. Despite the best of our intentions, it is nearly impossible for an individual to be devoid of the emotional biases that inevitably lead to poor investment decision-making over time. This is why all great investors follow strict investment disciplines to reduce the impact of human emotions.

Lastly, history offers endless proof. The dot-com mania, the housing bubble, and the “meme stock” frenzy shared the same behavioral DNA. Confidence became arrogance, diversification gave way to concentration, and the line between investing and speculation vanished.

The illusion of safety made investors their own most significant risk factor.

Breaking the Zero-Risk Illusion

The challenge for today’s investor is not merely spotting risk, but feeling it again. In a world where central banks have blurred the boundaries between market cycles, developing a healthy respect for uncertainty is an edge. Successful investors do not try to eliminate volatility; they prepare for it. They recognize that risk is not a variable to be avoided but a constant to be managed.

That starts with reframing risk awareness. Calm markets should not be a source of comfort but a warning sign that risk is being mispriced. Maintaining liquidity through cash or short-term instruments is not an act of fear but one of readiness. Cash provides optionality: the ability to act when an opportunity arises and others are forced to sell. Diversification should go beyond the surface level of asset classes; proper diversification comes from owning assets that respond differently to changes in inflation, liquidity, and interest-rate expectations.

Here are five practical steps to employ today before the next “event” occurs:

-

Reframe Risk as a Constant, Not a Variable: Risk doesn’t go away—it simply migrates from one part of the system to another. If volatility is low, it’s often being stored somewhere else, waiting to be released. Treat calm periods as warnings, not assurances.

-

Diversify by Source of Return, Not Label: Don’t just diversify across asset classes; diversify across drivers of return. Own assets that respond differently to inflation, liquidity, and policy shocks. Real diversification is behavioral, not cosmetic.

-

Maintain Cash as Optionality: Cash isn’t trash—it’s future opportunity. Holding liquidity during euphoric markets gives investors the flexibility to act when others panic.

-

Recognize the Fed Is Not Omnipotent: Monetary policy can influence liquidity, but it can’t repeal the business cycle. Believing otherwise is the foundation of the zero-risk illusion.

-

Measure Success by Time Horizon, Not Headlines: The best investors think in decades, not days. Their goal isn’t to beat the market every quarter; it’s to compound wealth across complete cycles by avoiding permanent losses.

Markets don’t punish greed; they punish complacency. The most dangerous words in investing are still “this time is different,” and the illusion of a risk-free market is just another version of that fallacy. As investors, our job isn’t to eliminate risk; it’s to respect it.

The irony of the zero-risk illusion is that it thrives precisely when markets are calmest. Lulled into comfort, investors stop hedging, questioning, and preparing. When volatility inevitably returns, the same psychology that fueled the rally becomes its undoing.

Just as important is recognizing that the Federal Reserve is not omnipotent. Policy can influence timing but not the laws of cycles or valuation. Believing otherwise invites the same complacency that precedes every correction.

Markets will always swing between fear and greed. The illusion of zero risk is simply the latest iteration of an old behavioral story; the belief that we’ve outgrown the past. But risk never disappears; it only hides until complacency pulls it back into view.

The best investors understand psychology deeply. They remain humble in good times, skeptical when everyone else is euphoric, and disciplined when the crowd forgets what real risk feels like.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 10/17/2025 – 10:50ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1