The Coming AI Debt Deluge

Authord by MBI Deep Dives

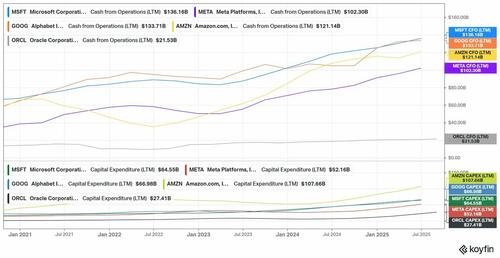

One of the core differences of the current AI revolution from the earlier bubble periods was that almost all of the funding so far has come from operating cash flow (OCF) of some of the most profitable companies on earth. Despite massive capex increases in recent years, all the major public companies (except Oracle) participating in this investment cycle has healthy Free Cash Flow (FCF) so far. Meta, for example, generated ~$50 Billion FCF in the last 12 months although one-third of it was just SBC. But cash is cash…if you need hundreds of billions over multiple periods to get to the promised land, there is still a healthy difference between OCF and Capex of some of these big tech. Investments funded by internally generated cash can go on for a long time as long as market remains receptive to such investments.

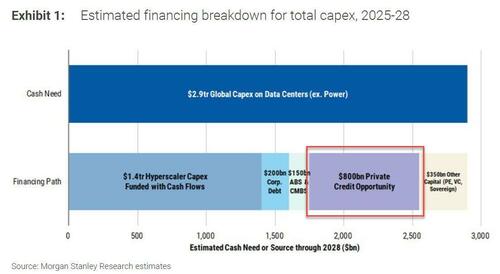

However, we are starting to see some changes in funding mix as debt has gradually come to the scene. One thing about debt entering the conversation is debt itself can be a great forcing function to manage the potential overinvestment cycle as interest payment obligations and balance sheet leverage can put some hard constraints to keep you disciplined.

Big tech understands this and hence are resorting to some “helping hands” in their investment journey. For example, last week Meta entered in a Joint Venture (JV) with Blue Owl Capital for their $27-Billion Hyperion Data Center campus, of which Meta will own 20% and the rest will be owned by funds managed by Blue Owl Capital. Meta is signing an “operating lease” with an initial term of only four years. They have the option to extend the lease every four years, but they are not obligated to.

To persuade the JV to accept the short four-year leases, Meta provided a “Residual Value Guarantee” (RVG) covering the first 16 years of operations. If Meta decides to leave (by not renewing or terminating the lease) within the first 16 years, they guarantee the campus will still be worth a certain amount of money (undisclosed). This payment is “capped” i.e. there is a pre-agreed maximum limit to how much Meta would have to pay. Again, we don’t know the exact capped limit in this deal.

The structure of this deal, featuring short 4-year leases combined with a long-term RVG on a highly specialized asset, closely resembles a financial tool known as a Synthetic Lease.

In a synthetic lease, the tenant (Meta) gains the flexibility of short commitments and favorable accounting treatment (keeping the debt off their balance sheet). However, to convince investors (Blue Owl Capital) to fund the construction, the tenant must assume the majority of the financial risks of ownership. The RVG achieves this risk transfer. To secure financing for such a massive, specialized asset, this cap must be set very high. While we don’t know the exact number, my guess is it’s likely somewhere between 80% to 90%. If we assume it to be 85%, for the $27 Billion Hyperion campus, Meta’s maximum possible exposure is $22.95 Billion.

If Meta decides to terminate the lease within the 16-year RVG period, the payout is determined by the following calculation:

Guaranteed Value at time of exit – Actual Market Value = Shortfall

Meta pays the shortfall, but only up to the agreed-upon cap (estimated at $22.95B). The guaranteed value is likely just a a pre-agreed schedule that decreases over the 16 years, representing the value the investors expect the asset to hold as they recoup their investment through Meta’s lease payments. Of course, actual market value (AMV) is the real variable here. If the specialized technology becomes obsolete or the market softens, the AMV could plummet.

Given Meta’s backing, the bonds issued to fund this investment received investment grade credit rating. However, the bonds were issued at 6.58% yield which is closer to junk bond yield.

Why is the yield so high? If the value of the data center catastrophically collapses due to obsolescence or for some other reasons, Meta’s RVG covers most of the loss, but the investors bear the portion exceeding the cap. Moreover, the debt belongs to the project entity, it is “structurally subordinated” to Meta’s own corporate debt. Investors demand a higher yield to compensate for this “tail risk”.

More importantly, the underlying collateral is a hyper-specialized AI data center. If Meta leaves, it’s likely that the facility cannot be easily repurposed. While the RVG mitigates the financial loss, the specialized nature of the underlying asset still influences the perceived risk and pushes the yield higher.

My guess is Meta (and other big tech) will do more of these deals going forward. In fact, just yesterday, Oracle appears to be raising debt even larger than Hyperion deal: $38 Billion for building data centers in Texas and Wisconsin. If the deal goes through, it would be the largest debt deal so far in AI infrastructure.

I am very curious to see what the yields will be for debts issued by Oracle, especially given their cash position and balance sheet leverage is considerably inferior than Meta’s. Moreover, if these companies keep doing these deals, the yield may only go higher as the risk for later debt deals will gradually increase for the bondholders. Perhaps AI infrastructure spree can cool a lot when the debt yields get close to double digit yield. Indeed, while debt funded infrastructure investments will certainly raise the risk profile of these companies, having some debt into the system can make everyone all on a sudden a lot more disciplined in their AI infrastructure investments.

There are, however, compelling reasons for companies such as Meta to deploy less cash from their own balance sheet and get as much helping hand as they can get as long as the market remains receptive to such deals.

While Meta is confident that the demand for compute will continue to grow massively, they are likely less certain about what kind of compute infrastructure will be optimal in five or ten years. A data center is typically a 20-30 year asset. If Meta built and owned Hyperion, they would be committed to the physical footprint, power delivery, and cooling design made in 2025.

I do want to note that in a separate blog post, Meta indicated that their infrastructure is built in a way to accommodate flexibility for their 1 GW data center project in El Paso, Texas:

AI, and its inference and training needs, is still evolving, so our design needs to balance what we know today with what we might know in the future. Different AI configurations will require different approaches to hardware and network systems designs, so our new data centers are built to accommodate flexibility. For example, we’ve designed the El Paso data center to have systems that can support both the traditional servers of today and future generations of AI-enabled hardware

If they can build such flexible design, why is the obsolescence concern still valid? My guess is “flexible design” often means that a future retrofit is possible, not that it is easy or cheap. At some point, the cost of retrofitting an old “flexible” design exceeds the cost of simply moving into a new facility optimized for the new technology. In any case, such flexibility likely only addresses the known unknowns and may not able to cater to unknown unknowns 5-10 years from now. The flexibility Meta is buying with the Hyperion lease structure is “strategic flexibility”. While design flexibility lets you adapt the asset, strategic flexibility affords you the ability to exit the asset, but of course, at a price!

Tyler Durden

Mon, 10/27/2025 – 14:20ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1