‘Latin American Kuwait’? Trump’s Looming War In The Caribbean Might Have Nothing To Do With Narco-Terrorism

Why is President Trump amassing such overwhelming US firepower in the Caribbean? We previously wrote that the clock is ticking on Washington’s looming anti-Maduro action – as the USS Gerald R. Ford aircraft carrier arrived in Caribbean waters Tuesday after Trump ordered it to depart the Mediterranean where it was on a scheduled patrol. A commander-in-chief doesn’t typically spend weeks and even months building up dozens of naval assets and 10,000 troops in typically uneventful waters like the Caribbean, unless he intends to do something big. To wit, Trump’s June strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities included a fraction of the Caribbean buildup.

“The United States only has 11 carriers, three are at sea at any one time,” said CSIS analyst and former US military colonel Mark Cancian. “So, moving one of them into the Caribbean is very significant, it does a couple of things. It puts more pressure on the Maduro regime, and it brings a lot of combat power into the Caribbean.” He previously called the Ford carrier a “use it or lose it” asset, saying “it’s so powerful and so scarce, carrier strike groups, that other regional commanders will want to use the battle group.”

Sources familiar with Trump’s plans told the Miami Herald that “The Trump Administration has made the decision to attack military installations inside Venezuela and the strikes could come at any moment … as the U.S. prepares to initiate the next stage of its campaign against the Soles drug cartel.”

Given the arrival of the Ford Carrier Group near Venezuela, which some reports have said could move toward neighboring Guyana as soon as Wednesday, this strongly suggests the threat of US military intervention against the Maduro government has sharply escalated.

“Mr. Trump will most likely not be forced to decide at least until the Gerald R. Ford, the United States’ largest and newest aircraft carrier, arrives in the Caribbean sometime in the middle of this month,” NY Times wrote just days ago. “The Ford carries about 5,000 sailors and has more than 75 attack, surveillance and support aircraft, including F/A-18 fighters.”

There’s still widespread speculation over the why? Is all of this really to combat narco-terrorists? One has to wonder what might be the final casus belli for when missiles fly. There’s also the question as to the ultimate scope of any military action. The Trump administration continues to insist this is all about ‘Narco-terrorism’ and the Fentanyl trade as the Department of War strikes boat after boat of suspected drug runners – while the Iran bombing back in June was at least more straightforward less shrouded in speculation and mystery, as the threat of nuclear weapons development was the clear objective. Why move a carrier group to merely deal with cartels or narco-smugglers?

President Trump had admitted in 2023 – while Joe Biden was in office – that in his first term he tried to overthrow Venezuela’s government and pillage its oil: “We would have taken [Venezuela] over. We would have gotten all that oil. It would have been right next door.” But he has also most recently denied that this would be a prime reason if he decides to use force against Venezuela.

The Tiny Petrostate

One immensely significant and historic regional Latin American conflict which could become a key ‘justification’ for Trump’s looming Venezuela adventure is a tiny rainforest country which has remained largely, yet is quickly becoming a petrostate in which a well-known US oil company is reaping massive rewards: Guyana.

You may have missed it if you blinked last March when Guyana briefly made headlines in connection with US policy and Venezuela. Secretary of State Marco Rubio had warned at the time: “It would be a very bad day for the Venezuelan regime if they were ever to attack Guyana or attack ExxonMobil. It would be a very bad day, a very bad week for them.” This was Washington’s response after days prior a Venezuelan military ship had entered a major offshore oil and gas field off the coast of Guyana and approaching an ExxonMobil contracted vessel. That early March incident itself came days after Trump canceled a key oil deal with Nicolas Maduro’s Venezuela, citing its failure to repatriate an adequate number of illegal aliens from the US.

While it has never been a secret that Venezuela sits atop the world’s largest untapped crude reserves, which was estimated at 303 billion barrels (Bbbl) as of 2023, lesser known is the persistent threat Venezuela represents to the US claim on the many billions of barrels worth of oil in the adjacent disputed Essequibo Region. Even on the mere level of exploration freedom and energy logistics related to this strategically vital area off Guyana and Venezuela’s coast, Washington permanently blocking the ‘Maduro threat’ here will be seen by hawks as justification. To understand this under-reported oil conflict, we’ve authored the below original research.

Maduro’s Explosive Letter to the Recent EU-CELAC Summit

On Sunday November 9, representatives of the European Union and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) met in Santa Marta, Colombia. This was the fourth summit encouraging dialogue between Europeans and Latin Americans “to deepen the historical ties that unite us, at a time when multilateralism is being questioned all over the world and there is a continued need for a more just, equitable and democratic international order.” At the end of the Joint Declaration there is a list of those countries that disassociate themselves from certain paragraphs, but there was only one that withdrew completely: Venezuela.

Caracas’s specific grievances are not listed in the document, but it is easy enough to see that the high-minded statements concerning “peaceful settlement of disputes and the principle of territorial integrity and sovereignty” may be upsetting to a nation who believes its own claims were violated by Europeans in the nineteenth century and then ignored by the United Nations in the twentieth. Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro wrote to CELAC to use the summit to right the wrongs done and being done to his country:

“The principle at stake today is clear and decisive: the sovereignty of states and the free self-determination of peoples. Venezuela declares this with absolute clarity: it does not accept and will not accept any tutelage. We do not accept that under euphemisms such as ‘security’ or the ‘war on drugs,’ the old Monroe Doctrine be imposed, seeking to turn our America into a stage for invasions and ‘regime change’ coups to steal our immense wealth and natural resources.”

Maduro’s declaration that Caracas “will not accept any tutelage” may not just hearken to the Joint Declaration’s principles statements by people with no skin in the game, but back to the 1899 when Venezuela chose to passively accept the judgement of an international tribunal whose intentions were anything but impartial. The current territorial dispute between Venezuela and Guyana, though revived due to the discovery of oil a decade ago, dates back not just to nineteenth century British maneuvering, but to the colonial competition of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when the Dutch began to cut in on Spanish claims to the America’s dating back to the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas.

Land of Gold, Bauxite, Diamonds, Oil: Roots of the Essequibo Region Dispute

The Spanish monarchy under Ferdinand and Isabella had no idea how large their claims were when they signed off on the treaty that granted them the rights to the Western Hemisphere. Despite the Spanish head start, the vastness of territory allowed emerging global empires, like the Dutch Republic who was a war with Spain from 1568-1648, a chance to colonize. It was during this Eighty-Year War that the Dutch West India Company established a colony on the Essequibo River. In the 1648 Treaty of Munster that ended the war, Spain recognized Dutch independence as well as the territories that they currently occupied which included much of the Essequibo River basin. Dutch success in the region led to the initiation of other plantation colonies along the major rivers of the Guyanas including the Courantyne, Berbice, and Demerara. Although Spain did contest the frontier with these Dutch colonies, other than suggesting the Essequibo River, there was no exact border. This was a problem left for future generations.

During the French Revolutionary Wars of the 1790s the Dutch Republic was occupied by France giving the British Empire a chance to take control of vulnerable Caribbean claims, specifically the sugar plantation colonies along the Berbice, Essequibo and Demerara Rivers. These settlements lay to the east of the Spanish Viceroyalty of New Granada and to the west of Dutch Suriname. After the defeat of Napoleon, the Dutch Republic was reconstituted as the Kingdom of the Netherlands and an agreement was made with Great Britain concerning the new territorial situation in the northern crest of South America. The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814 officially ceded the colonies of Berbice, Essequibo and Demerara to the British who in 1831 merged them into one new colony, British Guiana.

Failure of the Bolivarian Dream

Simultaneous to the Napoleonic Wars in Europe was the advent of the Latin American Wars for Independence. The situations were directly connected as the 1808 appointment of Napoleon’s brother as the new king of Spain set off a six-year war to liberate the Iberian Peninsula from French forces. Meanwhile in the vast Spanish American colonies, now cut off from their imperial capital, declarations of independence began to emerge from revolutionaries such as the famous Venezuelan Simon Bolivar. In 1811, Venezuela became one of the first to defy Spanish rule and initiate the decade-long fight towards independence, which it achieved in the early 1820s.

Although originally inspired by the “enlightened” fervor of the of American Revolution, Bolivar increasingly interpreted US expansion as detrimental to the freedoms he had fought for. In an 1829 letter “El Libertador” wrote “The United States appear to be destined by Providence to plague America with misery in the name of liberty.” Not only was the United States increasing the institution of slavery in North America, which Venezuela was in the process of abolishing, but, with the 1821 Monroe Doctrine, Washington had tried to warn off European meddling in the Western Hemisphere. This declared sphere of influence, which could be interpreted as protecting the newly created Latin American republics, often left them at the mercy of the emerging American hegemony.

Bolivar’s vision, often called the “Bolivarian Dream,” was that Spanish America could unite in some fashion politically, economically, and/or militarily so as to better protect their interests from the Atlantic empires. In an effort in this direction, Bolívar formed the Republic of Gran Colombia, which included the modern-day states of Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, and Ecuador. Much to Bolivar’s disappointment this unification dissolved in 1830 leaving Venezuela as its own sovereign state. One of the things this meant was that instead of a unified Spanish American stance, Venezuela alone would have to try to reconcile its eastern border with the powerful British Empire.

Arbitration in Paris, Not Caracas

The border between Venezuela and British Guyana was disputed throughout the nineteenth century. When the British attempted to get Venezuela to recognize a distinctive border based on their surveys in the 1840s, Caracas refused. The discovery of gold in the disputed region only encouraged British claims in the late nineteenth century. To resolve the disagreement, arbitration tribunals were established first in Washington D.C. in 1897 and then in Paris in 1899. In these negotiations the British represented their claims, but the United States stood in for Venezuela. There were five arbitrators in Paris: two British, two American, and one Russian. Venezuela had no direct participation. This was in keeping with the modus operandi of the day in which, much like at the 1884-85 Berlin Conference in which the rules for carving up Africa into European colonies were established, those nations calling themselves civilized took it up as their burden to establish peace. The Paris Arbitral Award of 1899 gave Britain almost 90% of the disputed territory. Caracas was helpless to protest.

Decades later Venezuela was shocked to learn of a secret memorandum in which it was admitted that British conniving had led to the unfair decision which denied Venezuela of its territorial claims. In 1962 Venezuela took the matter of the “fraudulent deal” to the United Nations which paved the way for the signing of the 1966 Geneva Agreement which provided a forum for talks between Venezuela and the soon to be independent Guyana. Violation of Venezuelan claims were acknowledged internationally, but no solution was accepted. Frustrated, both governments spent decades trying to eke out some advantage.

The Tiny Venezuelan Neighbor Growing Into A Petrostate

Washington’s relationship with Caracas during the Cold War was mostly positive. In exchange for American military and economic aid, Venezuela was a strategic anti-communist ally. That said, the Washington-Caracas suppression of leftist movements sowed deep-seated anti-American sentiment which came to the forefront with the presidential victory of Hugo Chávez in 1998. Chavez promised a “Bolivarian Revolution” rooted in social justice and used Venezuela’s rich oil proceeds to fund socialist programs. Chávez initially declared that the Essequibo region was Venezuela’s eastern most territory, but over time relaxed his rhetoric towards Guyana in hopes of forming an anti-Washington bloc with her neighbors.

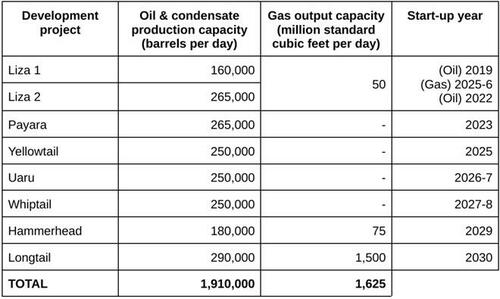

After Chavez’s death in 2013, Nicolás Maduro, a fellow member of Venezuela’s United Socialist Party, took charge. Two years later the territorial dispute with Guyana was resurrected with ExxonMobil’s offshore discovery of oil. The site, known as Stabroek Block, is in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of the Essequibo region which is claimed by both Guyana and Venezuela. The estimated billions of barrels of oil (Exxon touted its discovery of some 11 billion barrels worth) stood to radically enrich either country.

While Guyana granted ExxonMobil drilling rights, and the international community seemed to affirm its prerogative to do so, Maduro began to make threats. In 2018, Guyana requested that the International Court of Justice (IJC) declare the 1899 Paris Arbitral Award valid. Much to Maduro’s dismay, as Caracas had denied the jurisdiction of this court, the IJC stated in 2020 that it would evaluate the claims. With evermore barrels of oil being extracted to the profit of Guyana and ExxonMobil, Caracas continued to insist that the 1899 decision was invalid as it was rooted in deception.

In 2021, Maduro issued a decree claiming Venezuelan territorial rights extended two hundred nautical miles out from the Orinoco Delta. Venezuela then attempted to intimidate Guyana by capturing fishing boats and flying planes over a Guyanese town.

On October 23, 2023, Maduro put forward a law declaring the Venezuelan state of Guyana Esequiba into existence and granting the oil and gas rights to Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. Venezuelan troops moved on the border. An invasion of Guyana seemed imminent, but in December Maduro backed down and agreed to talks. White House national security spokesperson John Kirby responded to the situation by stating that, “We absolutely stand by our unwavering support for Guyana’s sovereignty.”

Increased Venezuelan threats and aggressions in the name of reclaiming its territorial rights in 2024 and 2025 have turned much of the international community against Maduro which help explain his frustration and challenge to CELAC during its recent meeting.

The Advancement of ‘Barbarism’

Although Maduro supporters in CELAC are few and far between, the organization does show solidarity with Venezuela against Washington’s use of extrajudicial strikes and gunboat diplomacy. CELAC was founded in Caracas in December 2011 and purposely excludes the United States and Canada. In some way it seeks to constitute the Bolivarian Dream of Latin American unity. The President of Colombia, Gustavo Petro, in his role as CELAC pro tempore president on Sunday, called on the countries at the summit to be a “beacon of light amid barbarism”. This is a not so subtle reference to American aggression in the Caribbean which he compared to the “bombs that fall on Gaza” stating that they have the “same manufacturing” as those that “now fall here on the poor”.

A key to understanding the territorial dispute between Venezuela and Guyana are the historic decisions made not in a democratic spirit of equality, but rather to enrich the imperial in the vein of the classic scramble for resources. Without naming names, Petro points his finger at the United States for its insistence to act unilaterally and therein calls on the members of the EU-CELAC summit to “tell the world that coming together, that dialogue among many, that a global democracy and a free humanity are possible today even as barbarism advances and kills people.”

Saddam vs. Kuwait, Latin America-version

The historic and persisting Venezuela-Guyana conflict has already been used by straight-laced interventionists to argue legitimate interests from Washington’s perspective (see Rubio’s quote from last Spring). They can point to the example of Venezuela’s territorial claim of over half of Guyana flaring up after the aforementioned immense offshore oil and gas deposits were recently discovered. They can also point to the fact that Caracas sees this as a historic and ongoing theft rooted in more ancient European imperialism, for which he seeks ‘liberation’.

All the dynamics are present for the Latin American version of a Saddam vs. Kuwait-style standoff and invasion which played out just ahead of America’s first Iraq War. It’s easy to see these parallels with Maduro as “Saddam” – given even just weeks ago he again threatened Venezuela’s tiny oil-rich and US-backed neighbor:

On October 3, Maduro’s vice president, Delcy Rodriguez, accused Exxon of funding a military assault in the region. The charge came less than two weeks after the Texas-based oil company announced a $6.8 billion expansion of its work in Guyana, which is engaged in a longstanding border dispute with Venezuela regarding the Essequibo region. “Guyana has opened the doors to the American, the U.S. invader, and the military aggression against our region,” stated Rodriguez, before adding that Exxon was “financing the Guyana government” for the action. (By contrast, the Maduro government has a longstanding, friendly relationship with Exxon’s fellow Houston-area competitor Chevron, which is responsible for nearly one quarter of the country’s oil production.)

In the scenario that the Guyana crisis gets invoked again by Trump admin officials in the coming days or weeks, the US may even decide that ‘preventative’ or preemptive military action is necessary in order to protect the home of one of the world’s fastest-growing oil basins.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 11/11/2025 – 19:40ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1