One of the lesser-known events in jewish history is the jewish revolt against the increasingly Christian Roman Empire in the years 351 to 352 A.D. which was centred on the region of Galilee.

To tell the story of what happened I will quote the narrative of the jewish writer and historian Bernard Lazare in his famous book ‘Anti-Semitism: Its History and Causes’.

He writes how:

‘Still the Jews did not behave passively in the face of their enemies, they had not, as yet, acquired that stubborn and touching resignation which became their characteristic later.

To the vehement discourses of the priests they replied by discourse, to acts they responded by acts; to Christian proselytism they opposed their own proselytism and vowed excretion on their apostates. Violent sermons were preached in the synagogues. Jewish preachers thundered against Edom, i.e., against Rome, the Rome of the Caesars which had become the Rome of Jesus, and which was now ravished the faith of the Jews after having ravished their nationality. While Gallus, Constantius’ nephew, governed the Oriental provinces, Isaac of Sepphoris raised the Judeans, being aided in his undertaking by a fearless man, Natrona, whom the Romans called Patricius. “Natrona,” exclaimed Isaac, “will delivered us from Edom, as Mordecai and Esther delivered us from the Medes, as the Hasmoneans liberated us from the Greeks.” The Jews took up arms, but they were severely repressed by Gallus and his general, Ursicinus. Women, children and old men were butchered, Tiberias and Lydda were half destroyed, Sepphoris was razed to the ground, and the catacombs of Tiberias were filled with fugitives who were hiding for months to escape detection and death.’ (1)

Now we can already see in that Lazare’s version of events the jewish responsibility for the rising of 351-352 A.D. is excused as ‘an understandable response to Christian provocation’ and the resulting Roman crackdown on what was after all a full-scale popular revolt in a Roman province – in the middle of both a Roman civil war (between Constantius II and the insurgent Roman general Magnentius; who had murdered Constantius’ brother Constans in 350 A.D.) and the year after a major Roman campaign against the Sasanian Empire centred on what is now Iran no less – is rendered by Lazare as an horrific atrocity by the ‘evil Christian Romans’ against the otherwise peaceful but unjustly insulted and persecuted jews.

The problem of course is that the actual Christian population of the Roman Empire was somewhere between 10 to 50 percent of its citizenry in the 300s A.D. and varied wildly between regions and between urban and rural areas. (2) Lazare is trying to have the Roman Empire be a completely – or near completely – Christian entity at this point so he can excuse the jews revolting by blaming Christian preaching and mob violence; much as he tried to claim the jewish ritual murder of a non-jewish boy at Imnestar in Syria in 415/416 A.D was ‘the result of Christian bigotry’ or ‘a Christian fabrication’ while his people – the jews – were innocent of doing anything wrong whatsoever. (3)

Much as Lazare lied about this, so we know he also lied about what happened in the jewish revolt against Constantius Gallus of 351-352 A.D.

Since as one of our principal sources on the events that took place – Socrates Scholasticus – writes:

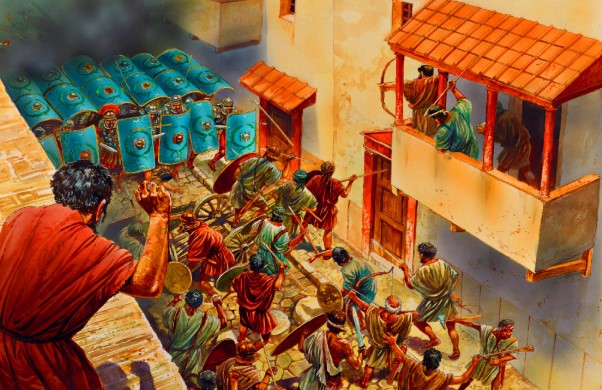

‘About the same time there arose another intestine commotion in the East: for the Jews who inhabited Dio-Caesarea in Palestine took up arms against the Romans, and began to ravage the adjacent places. But Gallus who was also called Constantius, whom the emperor, after creating him Caesar, had sent into the East, dispatched an army against them, and completely vanquished them: after which he ordered that their city Dio-Caesarea should be razed to the foundations.’ (4)

For the record Dio-Caesarea (alternatively Diocaesarea) is another name for Sepphoris, but we can see that what Socrates Scholasticus is describing here is that the jews of Galilee under their leaders Isaac of Sepphoris and Natrona rose against the Roman Empire after the Roman military campaign against the Sasanian Empire in 350 A.D. (5) which the Romans were still dealing with the result of in 351-352 A.D. (6)

We should further note Socrates Scholasticus’ words that the jews ‘began to ravage the adjacent places’ because the Byzantine chronicler Theophanes the Confessor writing in his ‘Chronographia’ describes how:

‘In this year there was an uprising of the Jews in Palestine. They killed a great many aliens, both pagans and Samaritans. Then their whole race was destroyed by the Roman army, and their city, Diocaesarea, was wiped out.’ (7)

The reason I highlighted Socrates Scholasticus’ words that the jews ‘began to ravage the adjacent places’ is because Theophanes is often claimed to be the ‘first reference’ to the jews deliberating try to exterminate non-jews in this context and because he was writing between 810 and 815 A.D.; (8) this is used as a reason to claim that he is not reliable when in Socrates Scholasticus was writing in the early 400s A.D. says much the same thing (i.e., he is writing only decades not centuries after the events he is describing) but doesn’t specify who the jews were ‘ravaging in adjacent places’ but due to the obvious anti-Roman focus of the revolt in the Galilee: the fact that it targeted non-jews (both Christian and Pagan) and jews who were viewed as ‘evil heretics’ (Theophanes’ ‘Samaritans’ referencing the Samaritan sect of Judaism) (9) as well as presumably jewish converts to Christians plus any jews who viewed as Roman collaborators as occurred in the First Jewish Revolt from 66 to 73 A.D. (10)

We can reasonably surmise that part of the reason for Gallus’ hard-line response and the fact that Lazare implies – reasonably I think – that he was running his own anti-jewish death squads and murdering jews wherever he found them is that the jews repeated the widespread anti-gentile massacres that had so angered the Emperor Hadrian when he crushed the Bar Kokhba Revolt (aka the Third Jewish Revolt) in Judea from 132 to 136 A.D. and so Gallus simply followed Hadrian’s somewhat successful policy of near-extermination of the jews in the affected regions and razing the jewish revolt’s capital to the ground (in this case Sepphoris rather than Jerusalem, which Hadrian rebuilt as Aelia Capitolina).

The accuracy of this interpretation is conceded by Isaac who comments that:

‘Aurelius Victor (Caes. XLII.II) reports briefly: ‘And meanwhile a revolt of the Jews, who impiously raised Patricus to royalty, was suppressed.’ Jerome also mentions these events: ‘The Jews rebelled and murdered the soldiers during the night and took their arms, but Gallus thereafter suppressed their rebellion and burned their cities: Diocaesarea, Tiberias and Diospolis, and many villages.’ (11)

Referring to the mentions of the jewish revolt in 351-352 in the Talmudic sources he continues by explaining that:

‘On one point, however, they are unanimous – namely, that Ursicinus visited several places in Palestine at this time, among them Diocaeserea. Ursicinus was the senior commander in the army of Orient. If he was present in small towns in Palestine, not long after the large-scale campaign by Shapur II in northern Mesopotamia, there must have been a real military need for him to go there. The magister equitum Orientis would not have interfered in a mere local police action. The dux Palaestinae, who had a considerable force at his disposal, could have suppressed limited disturbances.’ (12)

Put another way: the jewish revolt of 351-352 A.D. in the Galilee was significant and sizeable enough to overwhelm the local military forces that were used to deal with normal revolts and the regular Roman soldiers of the legions had to be called in to teach the jews yet another lesson in Roman military superiority and to wipe out the proverbial ‘nest of vipers’ once and for all.

This fits nicely with the references to the jews under Isaac of Sepphoris and Natrona engaging in the genocide of non-jews as well as other jews they viewed as heretics and/or traitors and actively attacking Roman forces from their base in the Galilee and showcases the falsity and hollowness of Lazare’s claims of ‘Christian persecution’ and his whining about the resultant Roman ethnic cleansing operation to make the Galilee jew-free in 351-352 A.D.

References

(1) Bernard Lazare, 1903, ‘Antisemitism: Its History and Causes’, 1st Edition, The International Library: New York, pp. 76-77

(2) See Rodney Stark, 1996, ‘The Rise of Christianity: A Sociologist Reconsiders History’, 1st Edition, Princeton University Press: Princeton, p. 19 and Keith Hopkins, 1998, ‘Christian Numbers and Its Implications’, Journal of Early Christian Studies, Vol. 6, No. 2, p. 191 for competing estimates.

(3) Lazare, Op. Cit., p. 76; on how this is complete nonsense that contradicts the historical evidence and scholarly interpretation see my article: https://karlradl14.substack.com/p/jewish-ritual-murder-the-imnestar

(4) Socrates Scholasticus, Ecc. Hist., 2:33

(5) Sozomen, Ecc. Hist., 4:7 agrees with Socrates Scholasticus, Ecc. Hist., 2:33

(6) Benjamin Isaac, 1998, ‘The Eastern Frontier’, p. 453 in Averil Cameron, Peter Garnsey, 1998, ‘The Cambridge Ancient History’, Vol. 13, 1st Edition, Cambridge University Press: New York

(7) Cyril Mango, Roger Scott, 1997, ‘The Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor: Byzantine and Near Eastern History AD 284-813’, 1st Edition, Clarendon Press: Oxford, p. 67; you can read the original text here: https://la.wikisource.org/wiki/Chronographia_(Theophanes)/AM_5843

(8) https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Catholic_Encyclopedia_(1913)/St._Theophanes

(9) To understand this, note the implications of what the jews are saying in the see the famous ‘Parable of the Good Samaritan’ in Luke 10:25-37 and how ‘unclean’ (= ‘evil’ = ‘goyische’) they are/were viewed as.

(10) Nachman Ben-Yehuda, 1995, ‘The Masada Myth: Collective Memory and Mythmaking in Israel’, 1st Edition, University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, p. 36; Shaye Cohen, 2010, ‘The Significance of Yavneh and Other Essays in Jewish Hellenism’, 1st Edition, Mohr Siebeck: Tubingen, pp. 149-150

(11) Isaac, Op. Cit., p. 453

(12) Idem.

Karl’s SubstackRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1