Fed’s Soft Landing Talk Meets Hard Data

Authored by Lance Roberts via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

The Fed’s soft landing narrative is a key theme in financial media, particularly on Wall Street, which expects a resurgence in economic activity in 2026 to justify increasing forward earnings expectations.

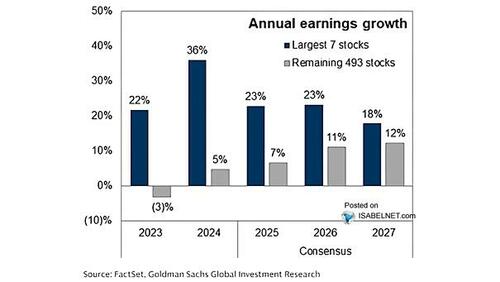

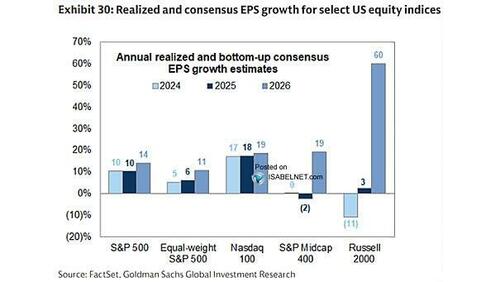

As shown, Wall Street currently expects the bottom 493 stocks to contribute more to earnings in 2026 than they have in the past 3 years. This is notable in that, over the past three years, the average growth rate for the bottom 493 stocks was less than 3%. Yet over the next 2 years, that earnings growth is expected to average above 11%.

Furthermore, the outlook is even more exuberant for the most economically sensitive stocks. Small and mid-cap companies struggled to produce earnings growth during the previous three years of robust economic growth, driven by monetary and fiscal stimulus. However, next year, even if the Fed’s soft landing narrative is valid, they are expected to see a surge in earnings growth rates of nearly 60%.

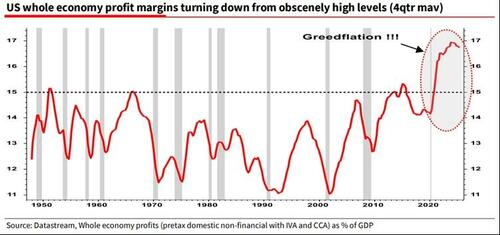

Notably, all this is occurring at a time when the entire economy’s profit margins have peaked and may potentially be turning lower.

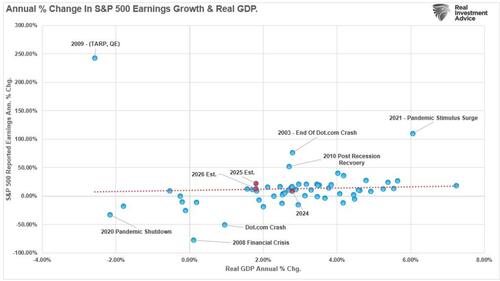

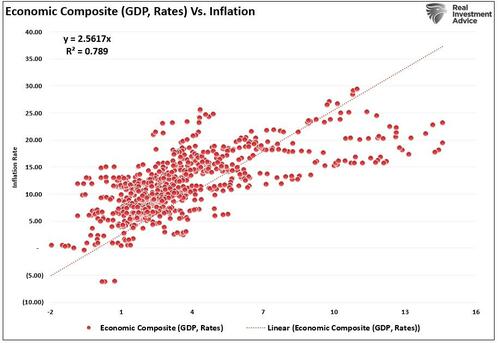

It should come as no surprise that there is a high correlation between economic growth and earnings, given that in a demand-driven economy, consumption is what generates revenues, and revenues ultimately develop earnings.

“A better way to visualize this data is to look at the correlation between the annual change in earnings growth and inflation-adjusted GDP. There are periods when earnings deviate from underlying economic activity. However, those periods are due to pre- or post-recession earnings fluctuations. Currently, economic and earnings growth are very close to the long-term correlation.”

The problem currently facing the Fed’s soft landing narrative is that it hopes the economy can slow without a recession, allowing inflation to return to its target. For now, investors have held the markets higher, hoping the Fed’s soft landing narrative comes to fruition, which would lead to a surge in economic activity. However, the latest employment, retail sales, and inflation trends suggest a potentially worse outcome, characterized by weakening demand and shaky consumer strength.

Those factors weaken the case for the Fed’s hopes of a soft landing and suggest an increase in market fragility.

Falling Inflation Tells a Demand Story

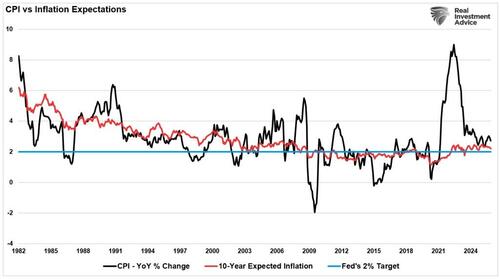

Let’s start with inflation. If economic growth were on the cusp of resurgence, expectations for inflation would be rising. However, as shown, those expectations never rose with “printed inflation,” because it was the “transitory effect” of massive monetary stimulus. The bond market’s view was that inflation would revert to its normalized levels as that monetary excess left the system, which has been the case. This is particularly notable, as inflation expectations have always been more accurate than the “inflation” bears we discussed yesterday.

In the Fed’s narrative of a soft landing, the trend in inflation expectations is crucial. Here is an essential point:

“The Federal Reserve WANTS inflation.”

Here is another critical point: So do you.

Without inflation, there can not be economic growth, increasing wages, and an improving standard of living. In other words, prices must always rise over time, which is why the Fed targets a 2% inflation rate, thereby supporting 2% economic growth. What we don’t want is “disinflation” or “deflation,” which would occur in conjunction with a recession, leading to job losses, falling wages, and reduced prosperity overall. As shown in the chart below, there is a high correlation between inflation, economic growth, and interest rates over time.

When inflation eases because demand weakens, the economy slows, producers lower prices to clear unsold goods, and employers become more restrictive in hiring and wage increases. Services that rely on discretionary spending lose pricing power, and banks become more stringent in their lending practices. These are not signs of a healthy expansion, but rather reflect a decline in spending power among households.

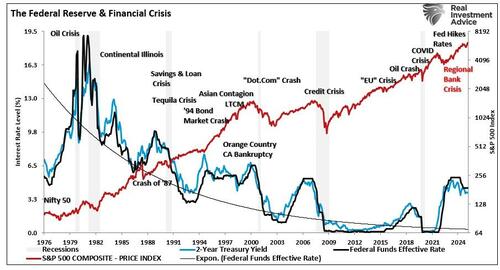

The Fed’s soft landing narrative is predicated on the hope that it can achieve its 2% inflation target without causing a more widespread slowdown. Historically, the Fed has failed in such attempts, as shown by the relationship between Fed rate-cutting cycles and economic and financial consequences.

As an investor, you need to distinguish between inflation caused by temporary supply/demand shocks, as we saw following the Pandemic, and inflation caused by organic economic activity. Supply/demand imbalances, such as higher input costs or a lack of supply caused by a geopolitical shock, can create a spike in inflation, which resolves itself when the shock is over. However, inflation caused by organic demand provides insight into the strength or weakness of the economy. Currently, we are focused on potential demand erosion as consumers cut back, employment weakens, and wages decline.

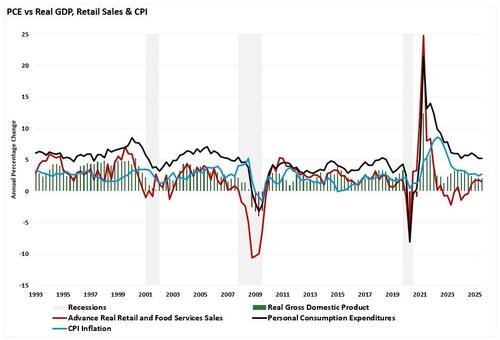

The retail sector provides early signals of demand weakness. Housing-related spending, auto sales, and discretionary purchases show stress, and many consumers face higher borrowing costs and lower savings. As shown, PCE, which accounts for nearly 70% of the GDP calculation, slowing inflation rates, and weak retail sales growth, all suggest that demand destruction is present in the economy. Such a development may further weigh on the Fed’s narrative of a soft landing.

As noted, the Fed’s soft landing narrative requires demand to slow moderately while avoiding recession. However, falling inflation driven by weakening demand and sluggish employment growth suggests a more profound weakness.

Retail Sales Growth Is Not What It Appears

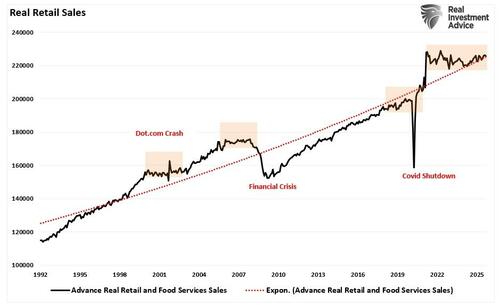

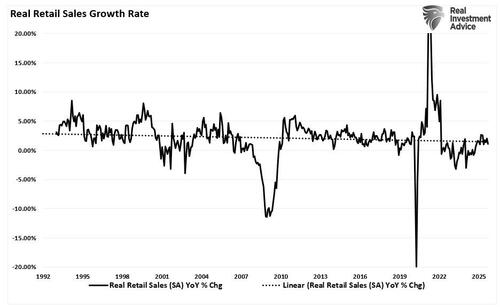

Headline retail sales reports often show month-over-month increases, which reporters interpret as evidence of resilient consumer strength. However, a look at the data tells a different story. For example, since 2022, real retail sales growth has effectively not grown. In fact, previous periods of flat retail sales growth were pre-recessionary warnings.

Secondly, the annual rate of change in real retail sales is at levels that have typically preceded weaker economic environments and recessions.

Notably, retail sales figures are subject to seasonal adjustments, which correct for typical spending patterns. During the holiday and back-to-school seasons, spending increases and the “adjustments” attempt to remove these effects. However, if the adjustment process overestimates normal seasonal strength, the adjusted result will appear firmer than it actually is. Secondly, another distortion comes from changes in price levels. If prices fall because demand weakens, nominal sales may rise while real volumes fall. Consumers buy less but pay lower prices. Nominal retail sales can mislead when viewed without context.

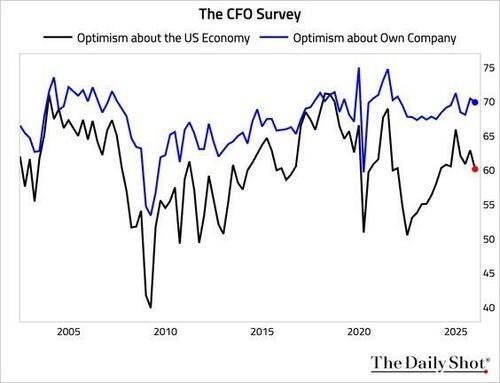

This is what we are currently seeing in the economy. As consumers pull back, businesses face the prospect of weaker revenue. That leads to slower hiring, lower investment, and falling confidence.

This matters for the Fed’s view of a soft landing. If consumer demand remains weak, the economy may slow more than expected, which increases the risk of recession. A “soft landing” requires growth to slow without tipping over, but current economic data points suggest a risk to that growth story.

The Market Risk If The Fed Is Wrong

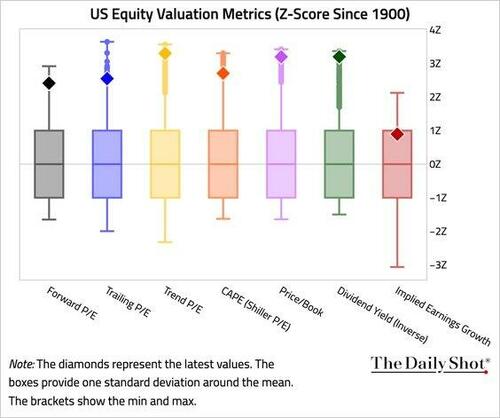

If the Fed’s soft landing narrative proves incorrect, the downside risk to investors increases significantly. The soft landing narrative has been factored into market prices, earnings expectations, and economic projections. Any deviation exposes valuations and portfolios to sharp repricing. With valuations already very elevated, the risk of a repricing event is not insignificant.

Wall Street’s forward expectations hinge on a growth rebound in 2026. Those projections assume that demand will return and margins will remain stable. However, there is no guarantee that either of those assumptions are accurate. If margins have already peaked, inflation declines as demand erodes, and employment falls, negative earnings revisions could be substantial. The year-over-year change in real retail sales, as shown in the chart, has hovered near recessionary warning levels. With consumers already strained by high debt service costs, weak wage growth, and declining savings, discretionary spending is under pressure, which directly affects earnings across cyclical sectors.

If demand weakens further, companies will face lower revenue and tighter margins. The margin compression will initially impact earnings, particularly for smaller firms with limited pricing power. A repricing of earnings expectations will follow, dragging valuations with it.

The Fed’s historical track record of avoiding recession during tightening and easing cycles is poor. Most rate-cutting cycles have been in response to financial or economic stress, not smooth slowdowns. If the Fed cuts rates next year, it likely won’t be in response to a soft landing. That shift in narrative would catch most investors leaning the wrong way.

Positioning for a soft landing assumes the Fed can control inflation without breaking demand. The data say otherwise. The risk, as always, is that the market wakes up to this reality too late. Therefore, investors should consider preparing for such a possibility in advance.

If the Fed’s soft landing narrative fails, investors will face a different environment than the one markets currently price. The assumptions behind strong equity valuations, tight credit spreads, and risk-on positioning will crack. If it does, that means you will need to act based on risk, not rhetoric. Here are some actions to consider.

1. Reduce Exposure to Overvalued Growth Assets: Tech and growth stocks led the rally on rate cut hopes and soft landing optimism. If earnings disappoint and rates stay higher, these valuations come under pressure.

- Trim overweight positions in mega-cap tech.

- Avoid speculative names with no earnings.

- Focus on companies with strong cash flow and pricing power.

2. Increase Cash and Short-Term Treasuries: If growth slows and volatility returns, capital preservation matters. Cash gives you optionality. Short-term Treasuries offer yield without duration risk.

- Rebalance toward 3-month to 1-year Treasury bills.

- Hold cash equivalents yielding over 4.5 percent.

- Avoid reaching for yield in low-quality credit.

3. Tilt Toward Defensive Sectors: Slower growth hits cyclicals and high beta sectors first. Defensive sectors hold up better in downturns.

- Favor healthcare, consumer staples, and utilities.

- Limit exposure to discretionary, financial, and industrial sectors.

- Screen for dividend sustainability and balance sheet strength.

4. Prepare for Credit Stress: If recession risk rises, corporate credit spreads will widen. Junk bonds will suffer. Bank lending tightens further.

- Exit high-yield bonds and floating-rate loans.

- Review credit exposure in bond funds.

- Consider higher-quality fixed income with lower default risk.

5. Be Patient and Opportunistic: If markets break, forced selling creates dislocations. You want dry powder ready.

- Hold 10–20 percent in cash or equivalents.

- Build watchlists of high-quality names at lower valuations.

- Add in stages as prices adjust, not all at once.

You don’t need to predict a recession. Instead, prepare for the potential risk if the Fed’s hopes for a soft landing fade. You can always increase risk more easily than recovering from losses. Remaining disciplined, protecting capital, and looking for opportunities is always the best course of action.

Trade accordingly.

Tyler Durden

Sun, 12/21/2025 – 09:20ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1