Just before this last Christmas (2025) we were treated to some rather unusual jewish kvetching rather than whinging that the Christmas narrative is anti-Semitic – this is indeed arguable as I’ve explained before – (1) but rather jews began talking about a somewhat obscure concept in Judaism that is largely limited to the Orthodox, Ultra-Orthodox and the Hasidic movement called Nittel Nacht.

Nittel Nacht has many different names in jewish culture that help us to understand how they view it: ‘Blinde Nacht’ (lit. ‘Blind Night’), ‘Vay Nacht’ (lit. ‘Woe Night’), ‘Goyim Nacht’ (lit. ‘Night of the Goyim’), ‘Tole Nacht’ (lit. ‘Night of the Crucified One’), ‘Yoyzls Nacht’ (lit. ‘Jesus’ Night’), ‘Finstere Nacht’ (lit. ‘Dark Night’) and ‘Moyredike Nacht’ (lit. ‘Fearful Night’).

Predictably jews didn’t cite the alternative pejorative names like ‘Goyim Nacht’ and ‘Blinde Nacht’ but rather the names that sound like the jews ‘were being persecuted by mobs of non-jews’ such as ‘Finstere Nacht’ and ‘Moyredike Nacht’. Then started whinging on Twitter/X about how jews ‘cower in their homes’ over Christmas because of ‘non-jewish Christians engaging in anti-Semitic riots in the streets’.

We can see this interpretation of Nittel Nacht in an article published by JTA in 2009 where we read how:

‘In medieval times, Christmas Eve was a night when Jews cowered in their homes in fear of marauding Christians.

Called Nitl Nacht by religious Jews, the night was one Jews traditionally refrained from the joy of study Torah — so as not to give the appearance of celebrating the Christian holiday.’ (2)

The problem with this interpretation is simple enough: it is complete and utter nonsense. This is immediately obvious when you look for historical examples of these ‘marauding Christians’ on Christian Eve and even jewish sources are unable to cite any actual instances of this happening.

The jewish writer and historian Yvette Alt Miller is so desperate for examples to support her thesis of ‘Christians abusing jews on Christmas’ that she can only find a total of three.

She writes:

‘One popular pastime was to force Jews to run naked through the streets of Rome for the amusement of others on December 25. These practices continued into modern times: in 1836 the Jewish community of Rome sent a letter to Pope Gregory XVI begging him to stop the abuse of the Jewish community on Christmas, in which rabbis were forced to don clownish outfits and run through the streets while spectators threw things at them. Pope Gregory refused to intervene.’ (3)

The fact is that this has nothing to do with Nittel Nacht either as it has to do with a peculiarly Roman tradition on Christmas day where-in jews were forced to run naked – or in clown outfits – through the streets of Rome as public entertainment not ‘marauding Christians hunting jews on Christmas Eve’.

Although that said it is genuinely amusing to think of overweight porcine jews being forced to waddle through the streets of Rome in nothing but their birthday suit or a pogo the clown costume while being jeered at by the inhabitants of the eternal city.

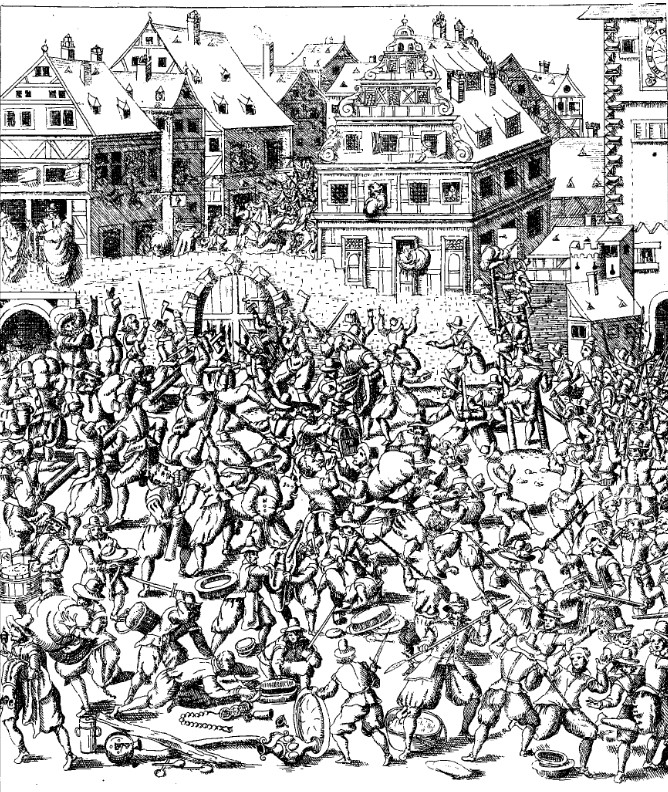

Alt Miller also brings up anti-jewish riots that broke out in the Holy Roman Empire on 25th December in 1312 but while she pushes them; they were actually minor and aren’t even mentioned by Guido Kisch’s standard work on the situation of the jews in medieval Germany. (4) Indeed, I can’t find much about them at all.

However, going on what we know about similar riots around the same time – such as that in Deggendorf in Bavaria in 1338 – (5) the anti-jewish riots of 1312 in Germany wouldn’t have been caused by nothing at all – as Alt Miller implies – but rather by jewish behaviour that would have probably have been either economic and/or religious in nature.

Once again, the anti-jewish riots of 1312 occurred on 25th December not the night of the 24th December so they have absolutely nothing to do with Nittel Nacht.

Alt Miller’s last example is also… well… scraping the barrel to say the least as she writes that:

‘In 1881, Jews were blamed for a stampede in a crowded Warsaw church on Christmas Eve that killed dozens of people. In the ensuing violence, mobs rampaged through the streets, attacking and killing Jews for three days in a massive Christmastime pogrom. Two Jews were murdered, 24 were hospitalized, many Jewish women were raped, and over a thousand Jews lost their homes and businesses.’ (6)

What Alt Miller is referring to here is called the ‘Warsaw Pogrom’ and occurred not on 24th December 1881 as she claims but rather on 25th December 1881. (7) This event came as a complete surprise to the Russian authorities in Poland as it happens (8) but as Ochs explains the reason for the ‘Warsaw Pogrom’ of 1881 was because of a belief – possibly real, possibly imagined – that a gang of jewish criminals had caused the stampede by raising a false alarm.

He writes:

‘There are different versions of how it began, but it is clear that on Christmas Day, 1881, a commotion broke out in Holy Cross church, which was filled to capacity. In the ensuing panic, over twenty people were trampled to death as the congregants rushed to the exits. Once they were outside, rumours apparently flew through the crowd that Jewish pickpockets had deliberately set the false alarm. A wave of beatings and plundering of Jewish homes and shops followed, which lasted until 27 December. Sources vary as to the number of fatalities.’ (9)

So thus, we can see that none of Alt Miller’s examples of ‘marauding Christians hunting jews on Christmas Eve’ refer to happens on Christmas Eve and one has nothing to do with anti-jewish rioting at all but was rather an annual Roman custom of apparent long-standing.

The more academically orientated jewish historian Rebecca Scharbach also cannot seem to conjure up any historical examples of ‘marauding Christians hunting jews on Christmas Eve’ and is instead reduced to just blithely claiming that ‘it happened’:

‘But it was also a Jewish one, called Nittel Nacht (Nativity Night). Jews refrained from reading the Torah, abstained from sex, and ate lots of garlic as they played cards all night long. The parallels are so striking because Nittel Nacht is actually a “Jewish adaptation of the [Christian] tradition.”

The difference was that instead of an army of the dead walking the earth, as Christians believed, there was only one: Jesus, born Jewish but now a sort of sorcerer. Christ walking on Christmas Eve was potent dark magic: On Nittel Nacht, “religious sparks are diverted to feed the power of evil; children conceived under his influence are spiritually corrupted; and the community of his birth cowers indoors.”

Scharbach calls this Jewish variation on Christmas Eve “a mystical calculus that speaks volumes about European Jewish anxiety regarding the Christian majority,” who could unleash murderous pogroms at a moment’s notice. Staying inside on Christmas Eve amid rowdy anti-Semites who believed Jews were responsible for killing Christ would seem a reasonable response to terror.

Nittel Nacht, argues Scharbach, was “not such a radical departure” from the Christian tradition at all, but this isn’t to suggest that it “is somehow less Jewish[.]” It spread quickly, suggesting that this “customary system fulfilled some widespread and urgent need within the early modern Jewish communities of central and eastern Europe.”

This history is “a tale of two unequal communities buffeted between social conditions that drew them together and distinctive communal needs that pushed them apart.” It also suggests why Nittel Nacht has been observed less often in the aftermath of the creation of the state of Israel: The violently anti-Semitic conditions that created the tradition don’t exist there. And over the last century, rabbinical authorities have spoken in favor of abandoning or limiting Nittel Nacht. As Scharbach writes, “Modern practitioners have found the Nittel Nacht observances increasingly irksome and meaningless, though many continue to observe them for the sake of tradition.”’ (10)

Thus, we can see that while jews are whinging that Nittel Nacht is all about ‘fearful jews’ hiding from ‘marauding anti-Semitic Christian mobs’ on Christmas Eve; the truth is that Nittel Nacht’s origins are not anti-Semitic but rather anti-Christian.

As Rabbi Joshua Plaut explains; Nittel Nacht was actually an anti-Christian jewish custom where jews would read the Toledot Yeshu – the most vicious anti-Christian textual collection in all of Judaism – as a deliberate insult to Jesus and Christianity as their Christian neighbours were celebrating his birth:

‘Over the centuries Jews developed customary Christmas activities. Certain East European Jews covertly read Ma’se Talui (The Tales of the Crucifix), a secret scroll containing derogatory versions of the birth of Jesus. Such legends are part of a genre of Jewish legends called Toledot Yeshu (History of Jesus). These legends first appeared in Hebrew in the 13th century (with possible earlier renditions written in Aramaic) and circulated in different versions throughout the Middle Ages. Toledot Yeshu describes Jesus as the illegitimate son of Mary by the Roman soldier Panthera. According to these tales, Jesus’ powers derived from black magic, and his death was a shameful one.’ (11)

Jews also deliberately gambled and played cards on Nittel Nacht since it wasn’t a jewish holiday, so it was permitted and it also had the double-side of being offensive to Christians for jews to deliberately engage in vice on a major Christian festival. (12)

This is in itself the origin of the Nittel Nacht tradition as Shai Alleson-Gerberg observes:

‘Mekor Ḥayyim, the commentary of the Ashkenazi Rabbi R. Yair Ḥayyim Bakhrakh (1639-1702) on Shulḥan Arukh, Orah Ḥayyim, is the earliest and the only Jewish source in the seventeenth-century to mention the custom of abstaining from Torah study on Christmas Eve, practiced to this day in Hasidic circles.

Earlier writings, however, reflect the existence of a unique Jewish tradition related to Christmas Eve, specifically, as Marc Shapiro shows in his fundamental article on Nittel, the writings of Jewish converts to Christianity reporting on what Jews do that night. For example, the sixteen-century convert Ernest Ferdinand Hess wrote in his book Juden Geissel (“Scourge of the Jews”, 1589) that on Christmas Eve, while Christians gather in churches to praise Christ, Jews assemble in their homes, and when they hear the church bells ringing, they announce that at that very hour the bastard (mamzer) is crawling through all the latrines (maschovim).

A similar description appears about half a century earlier in the writings of Johannes Pfefferkorn (1469-1523), and a few decades later, in those of Julius Conrad Otto (1562-1607) and Samuel Friederich Brentz (converted in 1601), all Jewish converts to Christianity. All three cases add that on Christmas Eve, Jews were accustomed to publically relate the story of Jesus, that is to say, they read the popular Jewish narrative Toledot Yeshu (“Life of Jesus”), also familiar as Ma‘aseh Toleh (“The Tale of the Hanged One”).’ (13)

So put simply: there is no historical evidence that mobs of ‘marauding Christians were hunting jews on Christmas Eve’ while the origins and reality of Nittel Nacht are not a ‘reaction to anti-Semitism’ but a viciously anti-Christian tradition designed to insult and degrade Christianity write large and Jesus specifically.

References

(1) On this please see my article: https://karlradl14.substack.com/p/philip-of-side-on-the-nativity-and

(2) https://www.jta.org/2009/12/18/united-states/whats-a-jew-to-do-on-christmas-eve

(3) https://aish.com/black-christmas-december-25-in-jewish-history/

(4) Cf. Guido Kisch, 1970, ‘The Jews in Medieval Germany: A Study of their Legal and Social Status’, 2nd Edition, Ktav: New York

(5) For the full story of what occurred and why please see my article on the Deggendorf anti-jewish rising of 1338: https://karlradl14.substack.com/p/deggendorf-1338-the-anatomy-of-anti

(6) https://aish.com/black-christmas-december-25-in-jewish-history/

(7) I. Michael Aronson, 1992, ‘The Anti-Jewish Pogroms in Russia in 1881’, p. 40 in John Klier, Shlomo Lambroza (Eds.), 1992, ‘Pogroms: Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History’, 1st Edition, Cambridge University Press: New York

(8) Michael Ochs, 1992, ‘Tsarist Officialdom and anti-Jewish Pogroms in Poland’, pp. 166-167; 174-175 in Klier, Lambroza, Op. Cit.

(9) Ibid., p. 181

(10) https://daily.jstor.org/nittel-nacht-the-jewish-christmas-eve/; others also cannot come up with a historical example while citing ‘jewish fear of marauding Christians on Christmas Eve’: https://forward.com/culture/327750/how-the-hasidim-observe-christmas-eve/; https://www.ekollel.com/can-i-learn-torah-on-christmas-day-or-nittel-nacht/; https://slate.com/human-interest/2009/12/the-little-known-jewish-holiday-of-christmas-eve-seriously.html

(11) https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/eastern-european-jews-christmas/; supported by https://slate.com/human-interest/2009/12/the-little-known-jewish-holiday-of-christmas-eve-seriously.html

(12) Idem.; also https://forward.com/culture/327750/how-the-hasidim-observe-christmas-eve/

(13) https://www.thetorah.com/article/nittel-nacht-an-inverted-christmas-with-toledot-yeshu

Karl’s SubstackRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1