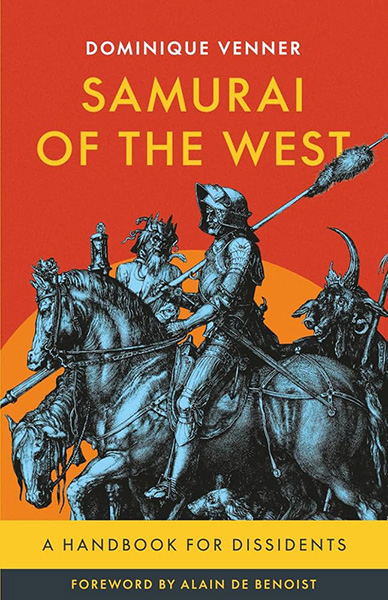

Dominique Venner, A Samurai of the West: A Handbook for Dissidents (trans. Alexander Raynor), Arktos Media, 2025, 205 pp., $17.96 (softcover)

Dominique Venner was a French activist, historian, and essayist, who died on May 21, 2013. He walked up to the altar of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, dropped to one knee, and shot himself.

His suicide note read, in part:

. . . . I love life and expect nothing beyond it, except the perpetuation of my race and my spirit. Yet, at the evening of this life, facing immense perils for my French and European homeland, I feel the duty to act while I still have the strength. . . .

I give myself death to awaken slumbering consciousnesses. . . . While I defend the identity of all peoples in their homelands, I rebel against the crime aimed at the replacement of our populations. . . .

The full suicide note is included in this new translation of what Venner called a breviary — “a collection of writings, reflections, and examples to which one can refer each day to nourish one’s thought, acts, and life” — that he said was “written by a European for Europeans.”

Alain de Benoist, who wrote the foreword, calls it “an invitation to become who we are . . . . an outstretched hand to lead us to the peaks, where the air is crisper, where forms become clearer, where panoramas reveal themselves and stakes become visible.” Anyone can profitably read this book, but it is primarily for men — men who love Europe and who are prepared to fight for it.

Dominique Venner was born in 1935, the son of an architect who was deeply conservative and nationalist. As Venner later wrote about his youth: “Everything was moving in a violent and unexpected way. Everything seemed possible. I wanted to be part of it.” On his 18th birthday, he volunteered for the army to fight the insurgency in Algeria. He returned to France and joined the nationalist group Jeune Nation. In 1956, with other members, he stormed and burned the headquarters of the French Communist Party in Paris in protest against the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution.

Venner was determined to reverse Charles de Gaulle’s decision to grant Algeria independence. He was arrested as part of a foiled plot to invade the Élysée Palace and assassinate the President. He was found guilty of “crimes against the state” and sent to prison for 18 months.

On his release, Venner gave up direct action but never regretted what he had done: “Without the radical militancy of my youth, without the hopes, disappointments, failed plots, prison, failures, without this exciting and cruel experience, I would never have become the meditative historian that I am.”

He wrote more than 50 books, including histories of the Russian civil war and of the Pétain era, a study of Ernst Jünger, and even a history of the American Civil War. A Samurai of the West was his last book, published posthumously. He completed it in the winter of 2012, with his suicide very much in mind. A friend reported that his “voluntary death” had been “long contemplated, meticulously prepared, and serenely carried out.”

In his translator’s note, Alexander Raynor writes that this book is “a message to those of us still living: remember who you are, and fight for what remains of our civilization before it is extinguished forever.” Mr. Raynor adds: “What once seemed like isolated voices of dissent have now become a chorus of defiance. The counter offensive for the survival of European civilization has begun.”

Venner never lost hope that Europe would survive. He was not a Spenglerian who believed in inevitable civilizational decline. He despised what the continent had become but Europe itself still lived: “What perishes are the apparent forms, such as political or religious institutions. But the roots of civilizations are practically indestructible as long as the people who were their matrix have not disappeared.”

Rebirth requires struggle, but Venner proposed nothing concrete, warning only that “politics has its own rules, which are not those of ethics.” To those who try to change laws, governments, and presidents, he wrote: “whatever your action, your priority must be to cultivate in yourself, each day, like an inaugural invocation, an indestructible faith in the permanence of European tradition.” As a handbook for dissidents, as Venner called this book in the subtitle, it makes stringent demands.

Degenerate Europe

The dispossession of Europe was, for Venner, an unspeakable horror, made possible only because Europe had become “a cowardly, amnesiac, shapeless, and guilt-ridden ensemble, seeking to protect itself from the violence of the barbarians through imploring and vile flattery.”

He was furious that in societies where the people allegedly rule, no one ever asked if Europeans wanted to be replaced. “Such is the reality of democracy,” he wrote, “that offers choices only between trifles.” The problem lay in a belief in Europe’s “universal vocation” to build “a supposed world culture” from which no one may be excluded. Europeans forgot that peoples are infinitely variable and that “only their animality is universal.”

And what is this “world culture”? A denial of everything ancient, beautiful, or heroic that makes Europeans who they are. Venner despised what “the Lords of our decadence” have built: “a world of sex, fun, and money” that accepts anyone, so long as he submits.

The “world culture” worships a new god called GDP, a perpetual-motion machine of economic growth, “dependent on the consumption of useless goods.” “In order to live better, one should perhaps consume less,” he wrote, and “free oneself from the madness of waste, from the consumerist drug.” Consumption alone could destroy Europe, because no society will ever voluntarily choose to consume less, and reckless exploitation will wreck the planet.

At the same time, “beauty has deserted our lives to shut itself away in museums.” Despite dazzling advances in technology, public buildings and art have become just as ugly as the “haggard and motley crowds” — both European and foreign — who swarm Europe’s streets.

Venner had other hatreds: Same-sex marriage was “an unbearable attack on one of the ultimate foundations of our civilization.” “Marriage is the union of a man and a woman with a view to procreation.”

What a man should be

Albrecht Dürer, Knight, Death and the Devil, 1513

In a degenerate world, Venner asked, “How can one not be a rebel?” On the cover of this book is the 1513 engraving by Albrecht Dürer called Knight, Death and the Devil. Venner calls the knight “the most famous rebel of Western art,” and he well understood rebellion:

The courage of a radical opponent in a period of civil war requires a nerve that makes that of the heroes of regular war pale. The latter received their legitimacy and the satisfactions of glory from society. Conversely, the radical opponent must draw his justifications from himself, confront general reprobation, the aversion of the great number, and a repression without brilliance. . . .

The rebel is in intimate relationship with legitimacy. He defines himself against what he perceives as illegitimate. Faced with imposture or sacrilege, he is to himself his own law by fidelity to trampled legitimacy.

These words have special meaning to some of us.

Rebellion is, for the most part, the work of men — the kind of men feared by feminism, which both denigrates virility and destroys femininity. Venner probably never heard the term “toxic masculinity,” but he understood the foolishness behind it:

The masculine alone [it is said] would engender a world of brutality and death. The feminine alone — that’s our world: fathers have disappeared, children have become capricious, soft, tyrannical little monsters. Criminals are not guilty parties, but victims or sick people who must be coddled. Psychologists multiply.

Venner unapologetically talked of the requirement that men be aware of “the horizon of war:” “The presence, even veiled, of war is what gives meaning and poetry to a society. . . . The erasure of war from the horizon of our history has led to the disappearance of masculinity.”

When not in actual combat, a man should always be aware of the potential for violence. He knows what is worth dying for, and is confident he would choose death when that is the honorable choice. Men should be physically fit and have a knowledge of combat sports.

However, Venner also lauded what he called “a feminine heroism that is not that of war. The daily heroism of women . . . is what conventional discourse speaks of least. And yet one must be blind not to see it behind the energy that is needed for the constant tasks that ensure the perpetual rebirth of life and are the essence of femininity.”

When Venner was in Algeria, war was present, not on the horizon. He admired the “supreme skill” of men such as paratroop colonel of the Third Colonial Parachute Regiment Marcel Bigeard, whose method for inspiring total loyalty was “to demand everything while offering in exchange only suffering and death.”

Marcel Bigeard

Venner quotes a journalist’s assessment of Bigeard and his men:

Fascists and paras refuse the suffering of the Christian religion because it represents a submission to a divine will. The Christian accepts suffering; Bigeard seeks it. He goes to it proudly, not with humility. Accepted suffering brings the Christian closer to his God; sought suffering makes the fascist a god.

Christianity

Venner devoted many pages of this book to Christianity, which he appreciated, but only as part of European history. He was not a believer, but he chose to end his life in Notre-Dame Cathedral, “which I respect and admire, she who was built by the genius of my ancestors on more ancient places of worship, recalling our immemorial origins.”

Venner had more sympathy with the spirit of the “more ancient places of worship,” and saw Christianity as an alien and dangerous accretion to the essential nature of his people: “If Europeans have been able to accept the unthinkable [replacement] for so long, it is because they have been destroyed from within by a very ancient culture of guilt and compassion.” He also wrote of Christian universalism that makes Europeans “undergo invasion as something normal, which the ruling oligarchies themselves have proclaimed desirable and beneficial.”

Venner noted that Jean Raspail, in his novel The Camp of the Saints also warned that Christianity crushes the spirit needed to defend the West. Venner also quoted the French political philosopher Pierre Manent: “Christianity has introduced an unprecedented gap between what men do and what they say. . . . the Christian Word asks men to love what they naturally hate — their enemies — and to hate what they naturally love — themselves.”

Venner wrote of prominent French intellectuals who abandoned the faith:

They had left Christianity, as one frees oneself from a foreign system, to rediscover the spiritual universe of their origins. A universe that had begun before them and would continue after.

Venner marveled at the doctrinal fights of the early church:

The religion of love . . . produced among its own an inexpiable hatred over questions that seem futile or incomprehensible to our eyes. It is in the blood and ashes of heresiarchs, amid terrible tearing, that the official doctrine was thus constructed.

Venner also criticized Christianity because there is no way to test its results — unlike governments, constitutions, and rulers: “This religion promised nothing on earth and everything in another world, of which it was the sole judge.”

Venner thought it was absurd for Rome to adopt an alien cult as the imperial religion. He notes, however, that Europeans molded it to their own traditions. Adoring Mary rescues women from the misogyny of the tempting and corrupting Eve, and the cult of the virgin was a return to pagan deities and even to fairies and sprites.

Venner also rejected what he called “Christian anthropocentrism,” as opposed to the pagan understanding that man is part of nature. He scorned the commandment of “the Jewish God:” “Be fruitful, fill the earth and subdue it.” Men should not subdue the earth, but protect it. They should honor the sacredness of springs, mountains, and woods, just as pagans do, and find any spiritual nourishment they need in the majesty of nature. Even the faith of Notre-Dame, Venner argued, is not “Judeo-Christian;” it is “Pagano-Christian.”

Photo credit: David Henry.

Apart from the faith, a church is still a haven from modernity, a place of calm, and an escape from vulgarity. Even for non-believers, an ancient and beautiful building is a monument to commitment, an expression of the European determination to build for centuries to come.

But today’s Christianity has lost its nerve. It dilutes its teachings, offers scripture à la carte, and foolishly thinks other religions are its allies. Lapsed Christians drift into cults of “the vaporous supernatural and compassion” that have the aroma of Christianity but none of its tradition of rigorous sexual, spiritual, material, or moral discipline. At the same time, “the Shoah has risen to the rank of civil religion in the West.”

Venner wrote that Communism and Fascism have no answers, and that both religion and philosophy are mute before the ultimate question: Why is there something rather than nothing?

For European man, however, “the vital feeling of belonging to a people . . . that precedes and survives him” is a kind of immortality more certain than anything promised by Christianity. “It is through history and awakened memory that I rediscover the forgotten foundations of European spirituality,” he wrote, and a man who builds on this foundation is as confident and unquestioning as a mountain or a river. “It is by deciding for oneself, truly wanting one’s destiny that one is victorious over nothingness. There is no escape from this requirement since we have only this life.”

Finally, for such men, the “meaning and poetry” of the “the horizon of war” are never far off:

I rebel against the negation of French and European memory . . . Threatened like all my European brothers with perishing spiritually and historically, this memory is my most precious possession. The one on which to rely in order to be reborn.

Our founding poems

How does a European become what he is? Venner called our civilization “a unique way of being women and men in the face of life, death, love, history, destiny,” and that unique way begins with Homer. The Iliad is our first tragedy and the Odyssey our first novel:

By narrating the trials and passions of very distant ancestors . . . they tell us that our anxieties, our hopes, our sorrows, and our joys have already been lived by our predecessors, who are also young, ardent sometimes to the point of madness, yet still wise and prudent. . . .

To Europeans, the founding poet recalls that they were not born yesterday. He bequeaths them the foundation of their identity. . . . The future takes root in the memory of the past.

Venner reminds us that countless literary works of antiquity have been lost, and many have survived only in fragments. It is only because of immense, persistent veneration for Homer that we can read his poems in their entirety. At the library of Alexandria, Homer was reportedly the most studied author. When Catherine the Great founded a port city on the Black Sea in 1794 after driving out the Turks, she named it Odessa, in honor of Odysseus.

For Homer, men are not slaves to Oriental divinities who impose arbitrary morals under the threat of horrible judgement. Venner explains:

Yahweh can create, modify, or destroy as he pleases and it is only by an effect of his good will that he created laws for the universe. This idea of a creative power, anterior and superior to the order of the world, is totally foreign to Homer and to the ancient Greeks.

For them, even the gods were subject to the eternal rules of the cosmos, which are older than the gods. Venner saw this as utterly unlike the religion of Israel for which there is nothing but the will of God.

Men, therefore, are “never judged according to abstract categories of an absolute good or evil, but rather according to what is noble, generous, equitable, or unworthy and base,” they are either “beautiful or ugly, noble or vile.” There is no beauty without courtesy, or without moral and physical poise. Ethics and aesthetics therefore go together, and freedom means conformity to the rational and eternal order of nature.

Thus, “the virtues sung by Homer are not moral but aesthetic,” and he shows this by example rather than explanation. Like the best philosophers, his characters teach wisdom not by what they say but by how they live.

Achilles and Hector, Penelope and Andromache are not ancients, but models for all time: “authentic men, noble and accomplished, [who] strove for courage and sought in action the measure of their excellence, as women sought in love and self-sacrifice the light that makes them exist.”

Canto IX of the Iliad was reportedly the favorite of the Greeks. Achilles says: “The life of a man is not found again; never again does it let itself be taken or seized, from the day it has left the enclosure of his teeth.” Venner argues that mere life has no value: “It is worth only its intensity, its beauty, the breath of greatness that each man — and first in his own eyes — can give it.”

Achilles is the hero of the Iliad: “Everything in him defies death. He thinks little of it, though he knows it is near. He loves life enough to prefer its intensity to its duration.”

And yet, Venner wondered whether Homer didn’t like Hector better. The Trojan prince is deeply attached to his wife and family, fiercely loyal to his homeland and unwavering in its defense. Venner wrote it is Hector’s words that best define the martial character of European man: “I do not intend to die without struggle nor without glory, nor without some high deed whose account will reach men to come.”

In the Iliad, men are at war and their duty is clear. Men are not always at war, but they must always have a sense of proportion and of reciprocal commitment: husband and wife, chief and subordinate, city and citizens. They count on qualities that will endure. “A society that can read its future in its past is a society at rest, without anxiety,” but “when war comes . . . all the people go to the ramparts, the enemy has no ally inside.” Always, the horizon of war.

Venner wrote that Homer is especially important in degenerate times, because he is the source of authentic European tradition, “the essence of a civilization over the very long term, what resists time and survives the disturbing influences of religions, fashions, or imported ideologies.” What smothers us today is not our permanent civilization. That must be sought in the best of what the past has been bequeathed us: “Greek civilization, born with Homer, is the mother civilization of all Europe.”

The spirit of Homer could even be the key to our survival:

From having been thrown down from the dominant position that was still ours before 1914, then plunged into an abyss of negation and guilt, we are the first Europeans to be positioned before the obligation entirely to rethink our identity by returning to our authentic sources. The Antiquity that we invoke is not that of scholars. It is a living Antiquity that we have the task of reinventing.

Samurai of the West

This book gets its title from a chapter called “A Detour Through Japan.” Venner respected bushido as the ethics of a military nobility, a refined cult of dignity that had much in common with the European spirit. Until Commodore Matthew Perry opened their country in 1853, Japanese were content to live in isolation according to their own codes. Japan was technologically unprepared to face the West, but Venner argues that no country was better prepared mentally — thanks to its martial spirit.

The goal of the samurai was perfect self-mastery, much like the goal of the stoics, whom Venner admired. Unlike in Europe, where there was constant tension between Sermon-on-the-Mount Christianity and the warrior spirit, the samurai had a religion that suited him perfectly.

The warrior/Zen master believed it was “necessary to prepare for death every morning and evening, day after day. . . . Thus does one escape the anguish of living and the fear of dying.” Venner writes of kamikaze pilots who failed to turn the tide of the war, but who went willingly to their deaths. Were their deaths useless? “Only suffered death has no meaning. Willed, it has the meaning one gives it even when it is without practical utility.”

Kamikaze

Venner saw in the kamikaze the spirit of the 47 masterless samurai who, in 1703, assured for themselves eternal glory in Japan for their loyalty unto death — painful, ritual death by seppuku. Venner likewise admired the suicide for spiritual and political reasons of the great Japanese novelist Yukio Mishima in 1970. No doubt, in their acts he saw the kind of meaning he expected to find in his own suicide.

Venner wrote that just as it was for the samurai, “learning to die well was the great affair of stoicism.” “Voluntary death” was “the philosophical act par excellence, a human privilege refused to the [immortal] gods.”

Cato the Younger’s death was one of the most famous suicides of antiquity. A staunch defender of the Roman Republic, he refused to live under what he saw as the tyranny of Julius Caesar and scorned the clemency he was offered as humiliating. “Now, I belong to myself,” he said, as he drew his sword to kill himself.

* * *

History is always unpredictable. No one alive in 1900 could have predicted the transformations, revolutions, and catastrophes of the century to come. No one could have foreseen that Europe would set off on the death march that Dominique Venner fought so hard to arrest.

He was surely right when he wrote:

A book never has the power to change the world, and it would be ridiculous to hope that it might. It is the world that changes and sometimes awaits new books. We have entered into such changes.

Just hours before he died, Dominique Venner wrote these words: “We are entering a time when words must be validated by deeds.” He lived, wrote, and died for a cause; its success or failure will be up to us.

The post Loyal Unto Death appeared first on American Renaissance.

American RenaissanceRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1