Europe Prepares To Unleash Anti-Coercion “Trade Bazooka” Against Trump: Here’s What’s In It

While president Trump took military force over Greenland off the table (for now at least) during his Davos speech, this makes a bruising diplomatic showdown virtually assured. And ahead of whatever trade escalation the Trump admin may announce next, EU leaders toughened their position and want the European Commission to ready its most powerful trade weapon against the US if Donald Trump doesn’t walk back his Greenland threats.

According to Politico, which cites five diplomats with knowledge of the situation, Germany joined France in saying it will ask the Commission to explore unleashing the Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI) at the emergency EU leaders’ summit in Brussels on Thursday evening. Berlin’s move brings the EU closer to a more forceful response, with Trump’s escalating rhetoric about the Danish territory and its supporters having prompted key capitals to harden their stance on how Europe should react.

“The resolve has been there for a few days,” one of the diplomats said. “We have felt it in our bilateral talks … there is very broad support that the EU must prepare for all scenarios, and that also includes that all instruments are on the table.”

Politico also writes that what governments request of the Commission meeting on Thursday would be decided largely by what the U.S. president says in his Davos address on Wednesday; and as reported earlier Trump maintained maximum pressure to force Europe to yield control of the territory to the US. Trump’s speech came as several European leaders had been trying to arrange meetings with the president on the Davos sidelines to talk him down from imposing the tariffs.

Aside from the anti-coercion tool, or “trade bazooka,” leaders have also discussed using an earlier retaliation package that would impose tariffs on €93 billion worth of U.S. exports. Two of the EU diplomats indicated that it is possible to impose the tariffs first, while the Commission goes through the more cumbersome process of launching the powerful trade weapon.

So what exactly is the ACI?

Europe’s “trade bazooka” has a 10-point list of possible measures on goods and services. They include:

-

Curbs on imports or exports of goods such as through quotas or licenses.

-

Restrictions to public tenders in the bloc, worth some 2 trillion euros ($2.3 trillion) per year. Here the EU has two options: Bids, such as for construction or defence procurement, could be excluded if U.S. goods or services make up more than 50% of the potential contract. Alternatively, a penalty score adjustment could be attached to U.S. bids.

-

Measures impacting services in which the US has a trade surplus with the EU, including from digital service providers Amazon, Microsoft, Netflix or Uber.

-

Curbs on foreign direct investment from the United States, which is the world’s biggest investor in the EU.

-

Restrictions on protection of intellectual property rights, on access to financial services markets and on the ability to sell chemicals or food in the EU.

The EU is supposed to select measures that are likely to be most effective to stop the coercive behavior of a third country and potentially to repair injury.

What does the ACI allow?

The ACI offers a broad and flexible array of countermeasures: its aim is not merely to reciprocate, but to provide the EU with calibrated responses depending on the nature and impact of the coercion:

- Trade measures are the first type of possible responses. These could consist of the imposition or increase of customs duties, import/export quotas or licenses and limitations on the free movement of certain products.

- Services and non-tariff measures can also be introduced. The instrument also provides responses in the services sector, for example restrictions on the provision of cross-border services, limitation of access to certain service markets, changes in access criteria or licensing for third-country providers.

- Controls on FDIs and public procurement are probably the most powerful aspects of the ACI. They allow the EU to impose restrictions on access to EU public procurement markets for entities of a coercive third country; they may limit foreign direct investment (FDI), particularly in sensitive sectors, or impose conditions on investors from third countries in strategic areas.

- The ACI also allows action on intellectual property rights, financial market access or certain export controls & licensing, reflecting the need to cover broader economic areas where coercion may manifest. That said, the ACI does not allow everything. In particular, restrictions must be targeted at specific entities of the coercive country and proportionate to the harm caused. Broad investment bans in the third country would exceed this framework. In addition, measures must comply with WTO rules and relevant bilateral investment treaties; broad restrictions on a major partner like the US could raise serious legal challenges.

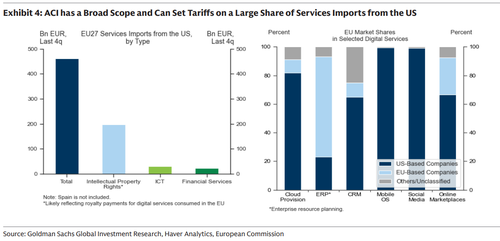

Specifically, the ACI could allow the EU to impose tariffs on services imports from the US. For reference, a flat 10% tariff on all EU imports of US services could mechanically raise about EUR 50bn in revenues.

That said, the US firms selling services into the EU have substantial market power, especially in digital services. This implies that European consumers would find it difficult to substitute away from services imports from the US and would likely need to shoulder a significant share of the services tariff. However, the ACI would also allow the EU to take broader retaliatory steps against US services companies, including an increase in the digital services tax (DST), investment restrictions or “buy Europe” clauses in procurement (such as defence).

Original purpose of the Anti-Coercion Instrument

According to Credit Agricole (full note available to pro subs), the EU’s decision to introduce the Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI) arose from a combination of geopolitical developments, trade conflicts and the perceived limitations of existing mechanisms.

In recent years, several third countries have increasingly used economic measures as leverage to influence EU or Member State policies. Notable precedents include China’s economic measures against Lithuania following its recognition of Taiwan’s representation, as well as repeated instances where countries applied unilateral tariffs, trade restrictions or investment barriers to press political demands. These cases highlighted that traditional WTO dispute settlement procedures were insufficient, since they typically address breaches of trade rules rather than coercive political pressure.

Against this backdrop, the European Commission proposed the ACI at the end of 2021. After a long EU legislative process, it was finally adopted by the European Parliament in plenary on 3 October 2023. The regulation was subsequently signed and entered into force on 27 December 2023

What it is, legally speaking?

The ACI falls within the broader scope of EU trade law. It is a directly applicable regulation (not a directive), meaning it bindingly applies uniformly in all Member States, without need to be devised in national law.

Its structure combines a clear procedural framework with an indicative list of possible countermeasures, while strictly regulating their use to ensure compliance with international law.

It defines economic coercion as a situation “where a third country seeks to exert pressure on the European Union or a Member State to influence a strategic choice or political decision by applying or threatening to apply measures affecting trade or investment”. This definition encompasses a wide range of practices, from punitive tariffs to restrictions on market access, services or investments.

The instrument applies regardless of the identity of the third country and whether the coercion is formal or informal, allowing the EU to respond to behaviours that might not be illegal under WTO rules but are used as political leverage.

How does the EU invoke the ACI

The ACI was proposed in 2021 as a response to criticism within the bloc that the first Trump administration and China had used trade as a political tool. European law gives the European Commission up to four months to examine possible cases of coercion. If it finds a foreign country’s measures constitute coercion, it puts this to EU members, which have another eight to 10 weeks to confirm the finding.

Confirmation requires a qualified majority of EU members, the support of 55% of member states representing at least 65% of the EU population, within 10 weeks. This is a higher hurdle to clear than that for applying retaliatory tariffs.

The Commission would normally then negotiate with the foreign country in a bid to stop the coercion. If that fails, it can implement ACI measures, again subject to a vote by EU members. These should enter into force within three months.

Since the ACI is European, the whole process takes an eternity to implement, and could take anywhere from a few months to a year to complete. By then, whatever plans Trump has vis-a-vis Greenland would be largely consummated.

According to Goldman, the EU will activate the ACI if the US escalates tensions further, but without implementing any measures immediately to leave additional time for negotiation. In other words, it is unlikely that any actual implementation of the ACI will take place in 2026 even assuming full-blown trade war returns.

More in the Credit Agricole and Goldman notes explaining the EU’s Retaliation Options available to pro subs.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 01/21/2026 – 12:40ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1