In 1963 Rhodesia found herself alone, again.

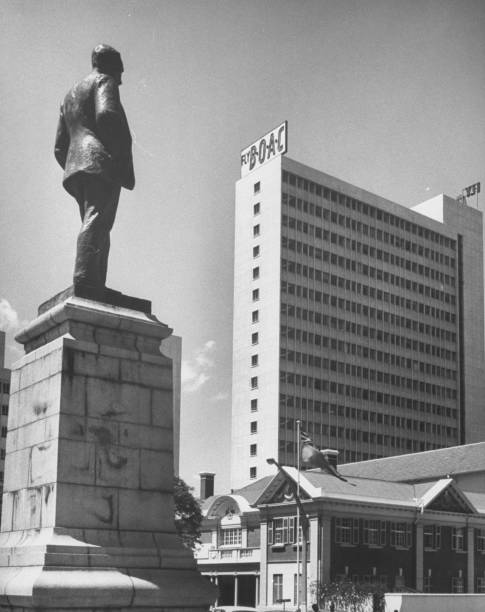

This was not a particularly unfamiliar situation for the Rhodesians, her future had always been somewhat up in the air and the little self-governing colony had always had options. Previously Jan Smuts had wanted to snap Rhodesia up, offering her people generous terms to unite with his thriving South Africa in the early 1920s. The Rhodesians, instead, opted to shake off Company (British South Africa Company, founded by Cecil Rhodes to colonise the region) rule and became a self-governing Colony.

Once more, this time after the Second World War, the Rhodesians had another decision to make about their future. There were three routes the Rhodesians could go down. First, the most unlikely, was the age-old idea of union with South Africa. The British were completely opposed to this, considering the South African racial policy to be abhorrent and beyond the pale. Secondly there was the idea of amalgamation with Northern Rhodesia, an idea both Roy Welensky and Godfrey Huggins (Northern and Southern Rhodesian Prime Ministers, respectively) favoured. Thirdly there was the option of independence.

The Rhodesian contribution to the Second World War had been immense and the Rhodesians had a proven track record of competent ruling by this point. The British had openly told the Rhodesians that they could have their independence if they wanted it in the form of Dominion status. Huggins had said: ‘We have proved ourselves, and our record is such that the British government has told me that Rhodesia can have its independence whenever they wish – it is there for the asking.’1

The Federal Experiment

Instead of taking independence then and there the Rhodesians suffered from delusions of grandeur. Amalgamation, which the British considered unworkable, quickly became Federation, instead. The British insisted that Nyasaland, a backwards little protectorate, or ‘Imperial slum’2 as Welensky (and future British PM Home) put it, to the east of the Rhodesias, be thrown in as part of the deal.3 Few could resist Federation fever. Ian Smith was one of the few exceptions that came out against the whole idea but eventually, he, too, converted. Of his conversion he recalls:

‘Huggins had come to the conclusion that an even better idea was Federation with Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. The Federation would be workable, big enough to be economically viable. At afternoon tea once, he said in my presence that the British had told him how impressed they were with the Rhodesian’s overall performance, their efficiency, their economic success, their honesty and loyalty, their racial harmony – no one could fault us. Whereas, by contrast, the colonial policy was a failure, Huggins said, and the British were hoping that we could transpose our successful system to Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

This sounded sensible and right, and the important thing was that we were working with people we could trust, the British. We had always worked together for our mutual benefit, and stood by one another when the need arose. We were in the fortunate position of dealing with proven friends, in fact with our own blood relatives. There were some who believed that in a crunch they would drop us, but I found that difficult to believe. Nevertheless, my instinct and training told me to be prepared for every contingency – after all, the British people had rejected Churchill after the war, and those socialists certainly had some strange principles and philosophies, so clearly there was a need to be on guard.

The plan for Federation was formulated, the legislation prepared, a referendum of all voters was held, and a clear majority supported the Federal concept. Generally my nature is to support positive, as opposed to negative thinking. Although I had reservations, I decided on balance to support the campaign.’4

Smith, like many others, lost his head in the clouds. He began to believe that after the formation of the Federation, ‘we should go north to try to take in the other British territories there… that is Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika, and then we should go south to Bechuanaland… I then feel that we should have to pause and consolidate ourselves before taking another step, and probably the final step. It will be best taken when it can be taken on a basis of equality in strength and numbers and therefore it would give equality in representation. This final step… is a Federation with the Union of South Africa.

I cannot help feeling that we are so tied up with the Union of South Africa, that we have so much in common with her, that this is the most important step of all… It is my feeling that going north is a necessary preliminary for going south.’5

Within a decade it was all ending in tears. The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was inaugurated on the 3rd of September 1953 and a secession clause had been specifically ruled out by the British. After all, ‘it would be right to describe a claim to secede as a precursor to liquidation’6, so naturally nobody in the City of London would ever think about investing in the Federation if such a clause were to be included.

The Rhodesians had been very wrong indeed to trust the British. Times were changing, and fast. Within a few years the British were already capitulating to African Nationalist demands left, right and centre. In a few more years the British were clearly moving towards reinterpreting the Constitution. Oliver Lyttelton, Secretary of State for the Colonies, had specifically said ‘I emphasise that this conference is not to decide whether federation has succeeded or failed, or whether it should be abolished or continued. Nothing of the sort; it is a conference to make such alterations as experience of its work has shown to be necessary during this decade, the first decade of its life.’7 and yet when the Federal review conference actually came around in 1960 it consisted of the Africans screeching about being allowed to secede whilst the British just sat in silence.

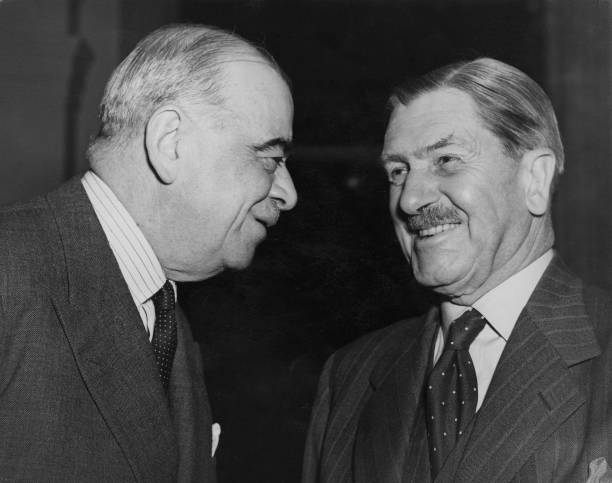

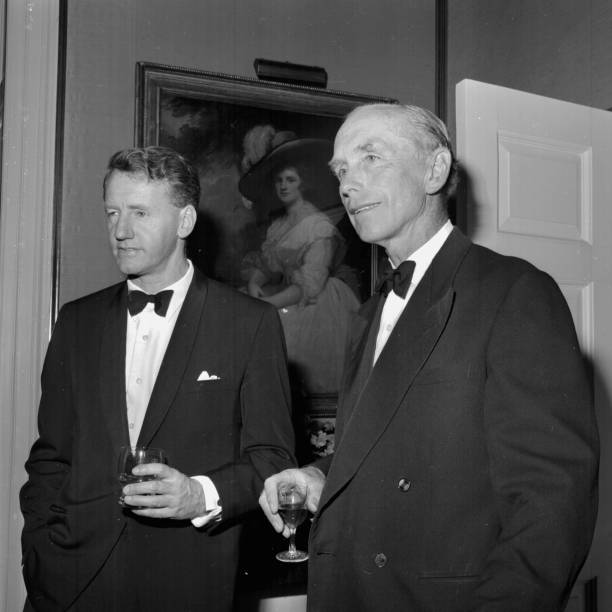

It was now just a matter of time. The death blow came in London in 1963. Welensky was invited for talks and whilst waiting for lunch with the Prime Minister, Harold MacMillan, the Deputy Prime Minister, Rab Butler, turned to Welensky and blankly read from a pre-prepared statement:

‘The lines of my statement, subject to interchanges today, will be: we start from the principle that any constructive policy in Central Africa must be aimed at working out a relationship between the Territories that is acceptable to them. We realise that the present situation cannot continue unchanged, and we have been trying to discuss with the Federal and Rhodesian Governments the basis of a conference at which a new relationship can be worked out. In the light of these discussions we have now decided that no Territory can be kept in the Federation against its will, and it follows from this that any Territory must be allowed to secede if it so wishes. Before any changes are made in the present association there must be further discussions, preferably at a conference, preferably in Africa, on the broad lines of a new relationship.

I realise the importance to you, Sir Roy, of what I have just said. I assure you it has cost me and my colleagues a great effort to arrive at this decision.’8

After years of betrayal in which the British had repetitively tied the Rhodesian’s hands behind their backs, the final nail had now been put in the coffin. Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland were to be allowed to break from the Federation, both were rife with African Nationalist violence, the former specifically anti-White violence, the most famous case being the Lillian Burton case, covered excellently in the article below.

Welensky could only turn to Butler and respond: ‘First Secretary, will you ask one of your officials to tell Mr. Macmillan that neither I nor any member of my delegation will be able to go to his luncheon today. I don’t want to be discourteous, but I cannot accept the hospitality of a man who has betrayed me and my country.’9

Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland were soon to break free. Both handed over on a platter to the Africans by the British. This just left Southern Rhodesia, once more alone, once more with a decision to make.

The Whitehead Years

The African Nationalists of Southern Rhodesia had gotten the message loud and clear, Britain would always capitulate and the wider-world would take their side. It didn’t matter how much violence they inflicted upon their own people or the White man, nothing could make the new liberal-order change their minds about racial equality. This was their new God now, the God of fairness, racial fairness. It did not matter if such ‘fairness’ destroyed nations, as it quickly destroyed Northern Rhodesia. All that mattered was the good feeling inside that came with caving in to African demands like a good liberal.

The Africans of Southern Rhodesia, like the Africans of Northern Rhodesia, quickly began a terror campaign. Firstly against their own people, the violence was ‘directed almost entirely to forcing Africans to join and to subscribe to the so-called nationalist parties.’10 Those without a paid up membership of the latest Nationalist organisation could find themselves having a hard time getting home unmolested after a long day at work. To not attend a Nationalist rally could spell serious trouble. One African named Muchenje was beaten to death for choosing to attend a boxing match instead in 1962.11 Those Africans who chose to fight back by joining the police reserve quickly found a petrol bomb flying through their window or a knife in their backs. Elspeth Huxley summed up the violence in The Sunday Times: ‘Intimidation by Congress members has been widespread and ugly and it has not been eliminated. ‘’Join us or we will come tonight and burn your house’’ is the usual form.’12

Whites were facing a very uncertain future indeed. The Africans were being allowed to run riot and it seemed that Southern Rhodesia was bound to follow in the footsteps of her northern neighbour. JRT Wood writes of the feeling amongst Rhodesians in 1960:

‘Despite the national income being at its highest level since joining the federation, with exports at record levels, mining output increasing and the best tobacco crop ever grown, the lack of confidence was driving people to sell their stocks, shares and property in preparation for emigration to Australia and New Zealand. Passages were booked up for two years ahead, and the increasing emigration had left 15 per cent of flats in Salisbury empty. The many cancellations of orders for new houses had caused a building slump. Unemployment levels were high and would worsen as many small businesses were ruined by the lack of orders. The result had been demands for a national government, a referendum on immediate secession, and the taking of a mass oath to defend Southern Rhodesia by force if necessary. Public opinion in Southern Rhodesia, always hitherto so loyal, was becoming frankly anti-British.’13

In December 1960 a Constitutional Conference took place, the National Democratic Party, the leading African Nationalist party at this time, were reluctantly invited. This new constitution, later known as the 1961 Constitution, strode a sensible middle course and set Africans on course for greater involvement in Government over time. Nkomo accepted the draft Constitution but soon came under pressure from his more extreme colleagues to renege. He rejected the terms out of hand ‘and then, by launching a savage reign of terror in the townships and tribal areas, virtually declared war on white government.’14

As the Constitution was making its way through the various parliamentary vetting processes the United Federal Party met to discuss it. The Chief Whip of the Party, forty-one year old Ian Smith, was the only one to raise his hand and query the absence of an independence clause. This, being 1961, was whilst the Federation was still in the process of collapsing. Smith’s point made complete sense. Rhodesia had been offered independence before the Federation, why would they not be entitled to it in the event of the Federation collapsing, which it seemed like it was about to? His concerns were waved away. To add in such a clause would imply acceptance that the Federation was doomed (sound familiar?). The referendum on the new Constitution went ahead as planned and passed without any trouble.

Only later was it noticed that the British had actually snuck in ‘an amendment so slight, and so cunning that no one noticed it until it was too late. Section 111 reserved on behalf of Her Majesty ‘the right to intervene by Order in Council notwithstanding anything to the contrary drafted elsewhere in the Constitution.’15 The Constitutional referendum had been sold to the Rhodesian public as a vote on eventual independence. Instead the British now had more powers, not less.

This was just the start. Kenneth Young writes:

‘Another Section made it clear that no Bill could become law until it had the assent of the Governor in the Queen’s name. It was clearly stated that the executive authority of Southern Rhodesia was vested in the Queen and might be exercised on her behalf by the Governor or such other person as may be authorized by the Governor. The Governor also in the Queen’s name could grant any person concerned in or convicted of any offence a pardon either free or subject to lawful conditions or could grant to any person a respite of sentence. He could also substitute a less severe form of punishment; he could remit the whole or part of any sentence and the offences to which this Section of the Constitution applied were ‘offences against the law in force in Southern Rhodesia other than a law of the Federal Legislature.’’16

Nkomo responded by running off to London to complain, whereupon he was told to just make the new Constitution work. Baxter writes:

‘Once recovered from his shock, Nkomo was given the hard-sell. Rhodesia, Cavendish explained, was a well ordered, functioning and viable country with an economy second in the region only to South Africa. Its industrial base was growing apace under the momentum of British capital, and frankly, it was difficult to imagine any circumstance whereby Britain would sacrifice all of this only to go the way of the Belgian Congo. He did not, of course, choose quite those words, but the message was clear enough. Do not anticipate majority rule anytime soon.’17

Once again Nkomo promised to behave himself and, just like last time, he was worn down by his extremists and resorted to the usual violence. It was uncovered that he was attempting to stir the country up into a frenzy so that the UN could be called in to ‘restore order’. Regardless, the British response really goes to show just how quickly politics could move in just a few years, especially in the 1960s. ‘Do not anticipate majority rule anytime soon’ very quickly became ‘majority rule now’.

Whitehead, meanwhile, had been darting all over the country on his ‘build a nation’ campaign in which he sought to bring blacks into the nation’s political life. At that moment in time the vast majority of blacks who were eligible for the franchise weren’t even bothering to register themselves. Politics just didn’t interest them. The few blacks who did actually take any interest in Whitehead’s campaign, again, quickly found a petrol bomb flying through their window or worse. An ‘orgy of beating, arson, intimidation and assault.’18 was unleashed upon the African population that didn’t completely bend to the wishes of the Nationalist terrorists.

There was also peaceful protests, one of which consisted of a crowd of Africans coming and interrupting the most sacred day on the Rhodesian calendar, Pioneer Day. A sit-in was staged in an attempt to mess with the proceedings. In response to this one Pioneer widow, joined by a young man, began to march around the Africans with a placard reading ‘Join the Zimbaboon club’.19 Another well-dressed White man appeared and began tossing peanuts at the Africans whilst turning to his fellow-Whites and shouting: ‘Look at the monkeys. They’re not really hungry. You can see they’re well fed. They don’t want the peanuts.’20 Tensions were rising.

Other protests aimed at the Whites weren’t as peaceful. One consisted of gangs of Africans storming into the White-only bars of Salisbury trying to stir up trouble. The Africans found themselves surprised at the ‘generally cordial welcome they received. In one or two bars they were actually served a drink and on a few occasions even stood a round.’21 The Nationalist thugs proceeded to charge through every single Whites-only bar in Salisbury smashing them up anyway.

On the 9th of December 1961 the National Democratic Party was proscribed and it’s assets were seized but the violence proceeded unabated. The terrorists simply founded new organisations and continued on as if nothing had happened.

Peter Joyce, an early biographer of Ian Smith, writes in Anatomy of a Rebel:

‘National Unity – the goal which Whitehead had striven for – crumbled, and the blame could be laid fairly and squarely on the doorstep of African extremism. The nationalists had deliberately torpedoed the white man’s sincere efforts to build a nation, and Whitehead drained the acid cup of disillusion.’22

Whitehead, clearly, was not doing enough. African terrorism was running rampant and he just wasn’t willing to go all the way to put a stop to it. Ian Smith amongst others began to circle the weak Prime Minister like sharks. Something would have to give.

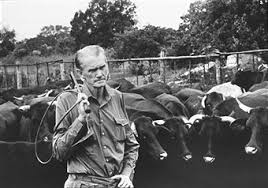

Smith had been to meet with Douglas ‘Boss’ Lilford, one of the richest men in the country and a Rhodesian patriot through and through. Smith, who had resigned from the UFP in December, pitched a new party to him and a life-long political partnership was sealed over a cup of tea at Lilford’s ranch. Many of Smith’s fellow ex-servicemen amongst others wanted him to be the leader of this new movement, but Ian insisted on Winston Field, a man with more experience in leadership than himself, a much more acceptable ‘establishment’ figure. Smith’s associates quickly fell in line. The Rhodesian Front was born in 1962 and Winston Field became it’s leader.

The Rhodesian Front’s policies differed in degree rather than in kind to those of the UFP, but, as Smith said, the point of the Rhodesian Front was for it to be a ‘rallying ground for people of different political parties who realised that if (the UFP Government) were not checked, we were going to lose our country. We marshalled our forces in order to prevent the implementation of this mad idea of a hand-over, of a sell-out of the European and his civilization, indeed of everything he had put into his country.’23

Meritocracy was a term frequently used by Smith, and this would be the cover for much of the Rhodesian Front’s plans. They would admit that sure, one day, the African may make up a majority in Parliament, but for that to happen it must be part of a long, gradual process in which the African was properly prepared for that kind of responsibility. If that were a dozen generations away then so be it. The party shied away from explicit racialism, the type of language that would appall the British, and instead opted for ‘merit’ which, they knew, and their supporters knew, meant White people for as many generations into the future as they could imagine.

From the get-go the party ran like a well-oiled machine. The UFP seemed tired and stuck in permanent drift by comparison. This was a serious force to be reckoned with and the nation began to rally around them.

In December 1962 the nation went to the polls and the Rhodesian Front won 35 seats against the UFP’s 29. Of these 29 there were 14 Whites, 14 Africans and one coloured MP. The Front’s MP’s, meanwhile, were all White. The following months saw a wave of mass-resignations in the UFP and Whitehead was replaced as leader. The Rhodesian Front were completely in the ascendent and showed no signs of stopping.

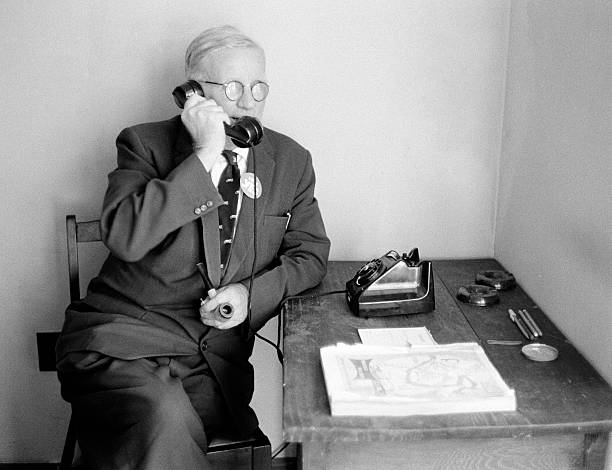

The Field Years

Field took the reins right as the Federation was winding up and, naturally, the Southern Rhodesians were needed at the disillusion conference, as JRT Wood explains: ‘If she did not attend, therefore, Butler could not act legally unilaterally to dissolve the Federation whatever the demands of the African nationalists.’24 This presented the perfect opportunity for the Rhodesians to secure their independence. Field, getting off to a strong start, stated in a strongly worded letter to Rab Butler that the Rhodesians would indeed be boycotting the conference unless their independence was discussed.25

Field, however, did not have the stomach that his successor would have. He was worn down over time with vague promises from the British and on the 7th of June Field dramatically declared to Welensky in the Federal Parliament: ‘I have played this non-attendance hand till the spots have worn off the cards. I’m going to the Falls conference.’26

And, so, the Rhodesians decided to attend that fateful conference later that month, completely putting the future of their country in the hands of Britain. Here, it seemed, their decision had been the right one. Rab Butler proudly declared to Winston Field:

‘I am in the pleasant position to be able to tell you that Her Majesty’s Government has given the deepest consideration to your request that Southern Rhodesia will get independence no later than the other two territories. In view of your country’s wonderful record of ‘responsible government’ over the past forty years, during which time you have conducted yourself without blemish, managed your financial affairs in an exemplary fashion and above all the great loyalty you have always given to Britain in time of war, not only in the two world wars but subsequently in Africa and with your air force in Aden, I have been asked to convey to you our government’s long-standing gratitude for your exemplary record, and to confirm that in these circumstances we are able and willing to meet your request.’27

Field went to fetch Ian Smith, his Deputy, so he could also hear this all-important promise.28 Smith, far more of a skeptic than Field, then asked if an agreement was about to be signed along these lines, to which Butler replied that in these matters between the British family there had to be trust:

‘In all these matters dealing with inter-family affairs, between the mother country and her colonies, there must be trust, because without that it simply would not work. Our record with you substantiates that, would you not agree? The thought of signing documents which could be subjected to legal wrangling is completely out of character with the spirit of trust which we believe in and which has characterised our Commonwealth. We will now work together in producing your new constitution, and that will be the document which we will both honour.’29

Smith could only laugh whilst Field naively remarked: ‘If you give your word to all of us here, as you have done, I accept that we must take it on trust.’30 Smith, however, turned to Butler as the meeting broke up and said softly whilst wagging his finger: ‘Let’s remember the trust you emphasised. If you break that you will live to regret it.’31

A few weeks later the Field followed up with Butler regarding the independence promise. Butler responded by feigning complete ignorance of such a promise ever being given.

In October 1963 Prime Minister MacMillan retired and was replaced by Alec Douglas Home. Smith, regarded as the ‘tough man’32 of the Rhodesian Front, was sent off to go and test the waters. Home and Smith got along well, the former going over the problems that came with giving the Rhodesians independence. First and foremost there was the Afro-Asian nations of the Commonwealth who were always baying for blood, demanding the most drastic measures against Rhodesia else they would withdraw from the Commonwealth and, ultimately, bring about its collapse. This the British refused to allow. Secondly, Home explained, there was a changing mood at home. The public were developing a curious anti-European mood when it came to Europeans in Africa, all of the black propaganda used against Nazi Germany had finally come home to roost, Nationalism or anything that benefitted the White race at the (perceived) expense of the other races was now deemed the worst crime in the world.

Smith countered by saying that he simply wanted an honouring of past commitments. Home said it was no good. The consequences of appeasement to the non-White nations of the Commonwealth, Smith went on, would bring about the end of Rhodesia. Again, Home wasn’t moved.

Smith’s meeting with Duncan Sandys, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, went much the same way. The future Prime Minister recalled:

‘He repeated and elaborated on the message which I had been given by Alec Home, stressed the danger of disrupting the Commonwealth, and told me that there would even be opposition from some left-wing Conservative MPs to the agreement for which we were asking. It would assist if we showed some flexibility and, for example, gave blacks greater representation in our Parliament. I told him forcibly that I was surprised at his suggestion, in view of the fact, as I was sure he was aware, that our blacks had the same access to the vote as did our whites. In addition, the 1961 constitution, the brainchild of Sandys and Whitehead, had introduced a ‘B’ roll to cater especially for our Black people, and the lack of greater representation of blacks in our Parliament could be traced to the fact that they had accepted the advice of their Nationalist leaders and boycotted the elections. I asked: what was the British government doing to put over this kind of message?

I was fed the typical evasive tactics which are the hallmark of British politicians.’33

The issue drifted until January, whereupon Field went to London himself for another round of independence talks. Once more the Prime Minister started off tough, implying heavily that Rhodesia could take matters into her own hands and declare independence. Saying it was one thing though, meaning it was quite another.

For now it worked. Sandys was taken aback and suddenly offered the status quo as an alternative to independence. This was not something the Rhodesians could accept, though, as Field explained. White emigration could skyrocket due to the uncertainty, the White population was, after all, the life blood of the country. The African Nationalists, too, knew that they could just call on Britain to interfere whenever they wished. This would be completely unsatisfactory to the Rhodesians. Something had to change.

Field fired off a letter back to Smith after his meeting with Sandys, stating that, ‘it soon became obvious that their attitude had changed a little and that what was wanted was a face-saver in regard to the Commonwealth.’34

It was the age old issue all over again. The British felt completely paralysed, unable to do anything at all lest they upset the non-Whites of the Commonwealth. Neither could the Rhodesians just directly be stabbed in the back. The only option was playing for time.

Field’s meeting with the Prime Minister went much the same way. The talks with Home were much more constructive but boiled down to the exact same problem, the Commonwealth. Field later recalled: ‘That so long as Sir Alec felt that he could help without upsetting the Commonwealth he would be prepared to do what was asked.’35 This, in reality, meant doing nothing at all.

Field’s trip came to nothing and soon enough a letter arrived from Sandys, completely dismissing all of the Rhodesian’s suggestions. Once more it was the same old song: ‘What we are concerned with is the likely reactions of other Commonwealth Governments to a decision by the British Government to grant independence to Southern Rhodesia, at a point of time when the franchise is incomparably more restricted than that of any territory which has acquired independence in the last fifty years.’36

Many, already, were beginning to feel that Field was too soft. The Rhodesians were being pushed around and offered no wiggle room in the slightest. In December 1963 alone 5,000 Whites had emigrated, obviously a completely intolerable situation given that there were only 221,000 Whites in the country as of the 1962 census. If this were to continue then investment would dry up, White resistance would cease, and the country would inevitably be handed over, making life for the remaining Whites intolerable. Even Field was losing confidence in himself in this situation. Something, once again, had to give.

A group of six MPs had approached Ian Smith before Field’s trip to London and, as Smith recalls: ‘expressed themselves most forcibly in their condemnation of the British government’s devious behaviour. Unless Field was prepared to confront them, he would have to go.’37

He would resist, for a time, but the pressure was mounting. At the next RF caucus meeting there had been fierce criticism of Field which only calmed down when Smith ‘backed him up and pleaded for patience for one more attempt’.38 Smith absolutely insisted on that one final trip to London.

The visit had clearly come to nothing. Smith could no longer hold back those demanding change and Field was voted out of office, Smith himself, naturally, became Prime Minister.

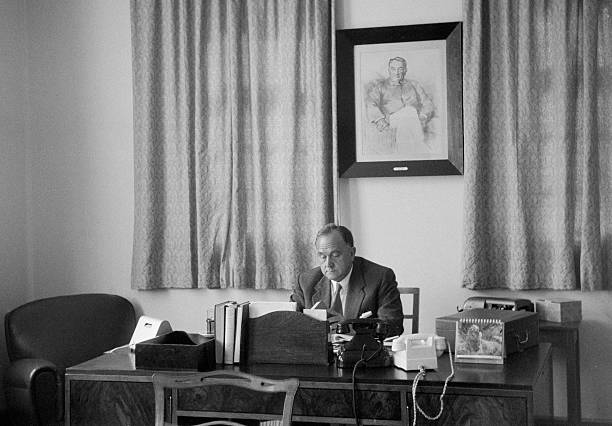

Smith takes the reins

UDI (Unilateral Declaration of Independence) fever had by now swept the country. The Rhodesians just wanted to get on with their lives, no matter what challenges that brought. The people required a sacrifice for the Government’s previous failures, this was found in the form of Field. Equally, a fresh start was needed to restore confidence, and this was found in Smith.

Smith, in his first press conference, promised to restore morale, get the economy moving and, most importantly, he said that he would halt the White exodus. Smith was the first Rhodesian-born Prime Minister the nation had had and, naturally, the people were able to connect with him on a different level. Smith had only ever visited Britain four times in his life, and even then only briefly. All he knew was Rhodesia. His roots were in Rhodesia, he had a Rhodesian accent, he spoke the same way as normal Rhodesians, rather than like a typical British politician of Eton or Oxford, the class which had consistently let them down. This was a man of the lower-middle classes, a man like them. Smith represented the reluctant hero and he painted himself in this same way:

‘I think I really am only in this because I think we have got to try to save our country. There is not much point in going on living here if we are not going to save our way of life and our country. This is basic. If I were satisfied that the future of Rhodesia was assured and that we were going the right way, I think I would then be very happy to withdraw gracefully and let someone else have a go.’39

The British, meanwhile, regarded this man as somewhat of a cowboy colonial, a half-foreigner, a man with whom they ‘could not talk on equal or mutually intelligible terms’40 with, an extremist (or a right-winger beholden to extremists), a ‘man of convictions so outdated, of tastes so naïve, as to make mutual understanding almost impossible’41. He was openly disliked by the British whom he was forced to negotiate with and the feeling was mutual.

Upon taking control Smith immediately took a harder line with Britain and got straight to the point. He wasn’t willing to give them the benefit of the doubt. He knew he was dealing with traitors. A message was fired off to the British Prime Minister reiterating Rhodesia’s claim for independence based on the 1961 constitution which had been signed by the British government. Home replied, as usual, asking if the blacks could be given greater representation in Parliament. Smith recalled in bewilderment:

‘But that was exactly what we had done only two years ago, with our new constitution. The British government had concurred. Why were they now going back on this?’42

The two countries began to drift even further apart and the rift grew even wider when, under non-White pressure, the British disinvited the Rhodesians from the yearly Commonwealth Prime Ministers conference, an insult of the worst kind which ‘cut the ground from the feet of such men as Whitehead who were pleading for restraint and no UDI, and united the Rhodesians behind Smith’s Government’43

Smith responded publicly on the 7th of June:

‘We are not excluded because we are no longer loyal to the Crown or to the ideals on which the Commonwealth was founded. We are excluded because the Commonwealth has outgrown itself and there is no longer room for us among the motley of small countries which have recently been granted independence and admitted to the Commonwealth without regard to their adherence to the ideals and concept on which it was founded. I wonder if we are really wanted in the Commonwealth any longer, and if we can serve any purpose by remaining.

I have tremendous respect, admiration and loyalty to the Queen, but she is no longer the Queen we used to know. She can no longer speak her own words. She is now the mouthpiece of party politicians in Britain and can’t speak her own mind and heart. Even if the Government were to become Communist, she would have to speak their words.’44

Rumours began to swirl back in Britain that a UDI was imminent, Home, however, was less affected by propaganda and reached out to Smith, inviting him to London, an invitation which was accepted.

On the 2nd of September Smith left Rhodesia, making a quick stop in Lisbon on the way where he met with Salazar, the Portuguese dictator. The two had ‘much in common’45 and got on fabulously. Most importantly, in regards to UDI Smith was told that ‘the leadership in Mozambique did not always follow metropolitan policy’46, exactly what Smith wanted to hear.

Smith arrived in London on the 6th where he was well received by the hero-starved British public who ‘took him easily to their hearts’47. The talks with the British came down to a few of the usual fundamental problems. The British demanded greater African representation, but refused on elaborate on what they actually had in mind for this. Any changes to Rhodesia’s status would require the full support of the Majority, Home insisted, but the question was how to test this support. Smith insisted that the Chiefs and Headmen of Rhodesia were ‘the best means of testing African opinion’48. This was how the Africans had always lived and three-quarters of the nations Africans fell under this Chiefly authority. This was rejected out of hand but ‘nobody around the conference table was able to suggest what additional methods would be most suitable’.49

The British also insisted on the release of Rhodesia’s detainees, all of whom were detained for terrorism and the like, not for their political beliefs. The first day’s talks came to very little and the following day brought the same old question of how to test African opinion.

The main problem, though, was that the British didn’t want to come to any decisions yet. An election was coming up soon and giving Rhodesia independence, the Conservatives felt, would negatively impact their odds.

Smith recalled:

‘Alec Home assured me that if the Conservatives won the election we would reach agreement within months. Sadly, political analysts believed Labour would win. And when the British electorate cast their votes, no one would be thinking of Rhodesia. They would be influenced by their own lives, and rightly so: the cost of their bread and beer, health and education services, availability of jobs and accommodation. Little would they know that the fate of a great though small country, Rhodesia, some 10,000 kilometres distant, could be prejudiced by their vote.’50

Evan Campbell, Rhodesia’s High Commissioner in London, had been holding private talks with Home previously and had been given the same message. Joyce writes:

‘The message was that, if the Conservatives retained office at the impending general election, the United Kingdom would grand Southern Rhodesia her independence within two years provided only that African education and African economic advancement were accelerated to provide more Africans for the two Rolls. No constitutional amendments were envisaged. Heartening news indeed.’51

Smith took the initiative and hosted a Great Indaba, a great meeting of the Chiefs and Headmen in which 620 were present. There was precedent for this such as Rhodes’ famous Indaba during the Second Matabele War or when Responsible Government and Federation were proposed. To go about this in any other way would have actually been seen as offensive and a challenge to the authority of the Chiefs52. Besides, it would be impossible anyway, as Smith explains:

‘The fact that the majority of indigenous people were illiterate, and did not possess birth certificates, compounded the difficulties. It would be virtually impossible to guard against a number of malpractices associated with voting, such as identifying people and avoiding multiple votes. One also had to overcome the people’s natural resistance to a system which was foreign to them. And probably most important of all, there was limitless potential for organised intimidation.’53

On the 22nd of October the Indaba took place with observers turning up from various European countries as well as South Africa. Britain, importantly, did not send observers even though just a few years earlier, in 1960, the Monckton Report had concluded:

‘It is important that nothing should be done to diminish the traditional respect of the Chiefs. In Southern Rhodesia it is part of the Government’s policy to increase the prestige, influence and authority of the chiefs in their tribal areas. We endorse this policy.’54

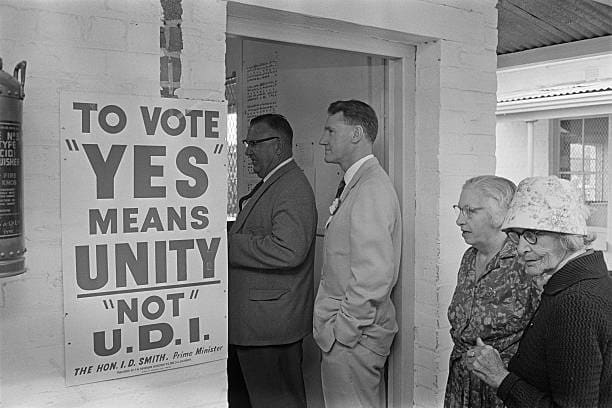

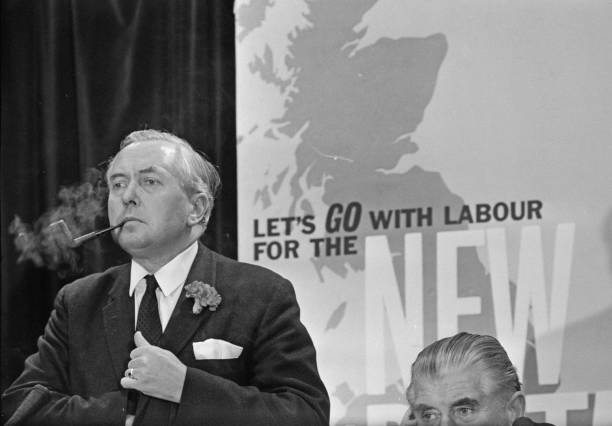

The natives returned a verdict entirely in Smith’s favour and a general referendum was then held in the country at large over the independence question which returned an equally as supportive verdict. Back in Britain, meanwhile, Harold Smith and the Labour Party had just come to power. The Indaba results were rejected as a fair means of testing opinion.

In October 1964 Secretary of State for Commonwealth Affairs, Arthur Bottomley, openly endorsed African violence during an interview at London Airport, remarking: ‘Like all people who are struggling to get their rights, if you are not allowed to do it by lawful means, sometimes other methods have to be employed.’55 Wilson was equally as distasteful, beginning his premiership with threats and bluster, there were even open attempts to meddle in Rhodesian affairs and an attempt to blackmail the Rhodesians by withholding funds from them which they were owed. All of this, naturally, drew the Rhodesian people closer to Smith, who they were closing ranks around.

Alec Home, now Leader of the Opposition, was aghast, remarking that: ‘Anything more inept, it is impossible to imagine, or anything better calculated to thwart the objective which I know that the Prime Minister has in mind. If that is not interfering in the internal affairs of another country, I do not know what is. That is something which so far all parties have been able to avoid.’56

It was hard to fix the rift. Right before the election Wilson had written to a keading African Nationalist stating that: ‘The Labour Party is totally opposed to granting independence to Southern Rhodesia so long as the government of that country remains under the control of the white minority.’57 Whenever Wilson would deploy some form of delaying tactic in the form of a vague offer to Smith, the Rhodesian PM would simply remind his British counterpart of the letter. The reply was always evasive.

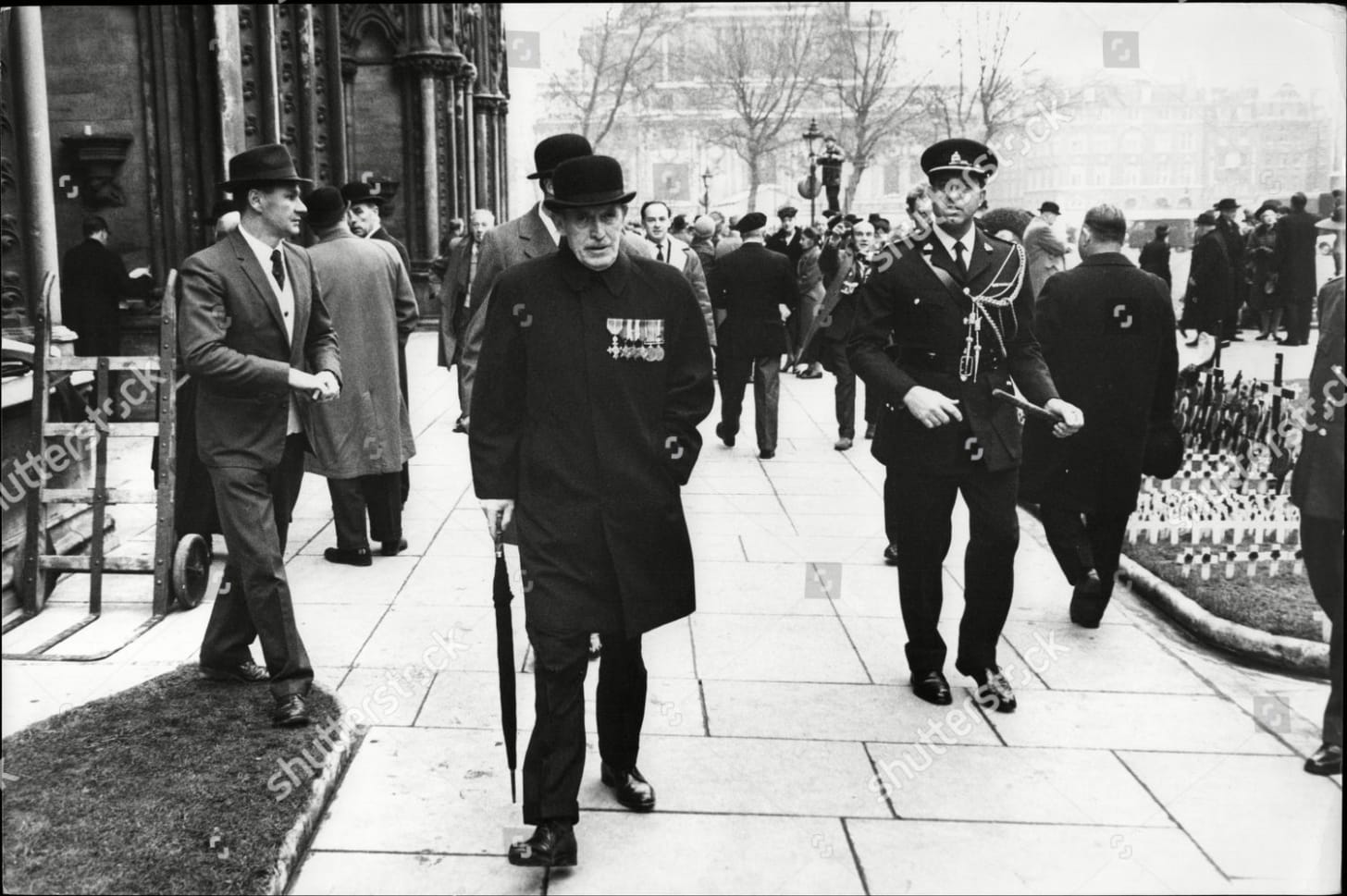

The two were forced together by the death of Winston Churchill as the former wartime Prime Minister’s will had contained an explicit demand that Ian Smith be invited to the funeral. Wilson did, however, make sure that Smith didn’t receive his invitation to lunch with the Queen. Her Majesty herself had to point out the Rhodesian’s absence and called for him, the Queen’s Equerry finding Smith in a Mayfair restaurant and handing him an the invitation. Wilson could only sit a short distance away, seething, whilst Smith, in regards to both the Queen and Prince Philip, was ‘impressed, too, by the amount of time they devoted to talking with me, and by their sincere hope that our problem would be solved amicably. It was a happy and worthwhile occasion, which gave me the opportunity to meet and chat with a number of people, including some Asians who were most friendly and considerate over the problems we were facing. A few of the black delegates also spoke encouragingly.’58

Regardless, the two were in the same place and agreed to have a talk, which they did later at Number 10. It was suggested that Smith use the side entrance to avoid publicity, which he did, but Wilson would later lie in his memoirs and make this seem like Smith’s idea, even though Smith was, after all, extremely keen for the press to hear his side of the Rhodesian story.

The talks only further exposed the reality that the two sides had irreconcilable differences, but, regardless, a British mission to Rhodesia was agreed upon which saw the British delegation (the PM did not come) travel across the country meeting various groups. The Chiefs, for example, made it clear in the strongest of terms that they would stand by the Government. One of them remarked:

‘It is obvious to us, sir, that however much truth we can speak today, it is not the intention of you, our honoured guest, to be satisfied with what we know to be the truth. If we take you to the graves of these people who have been killed you will not be satisfied that they have been killed by these nationalists. If we show you the graves of the children of our people who have been killed by these people, you will not be satisfied. If we show you the churches, the dip tanks and our schools that have been damages by these people, you will not be satisfied. Sir, if it is your wish to hand over to the nationalists, well, we cannot stop you. But all we can say is that if you do, the time will come when the person who is about to die will point a finger at you.’59

The British also met with the African Nationalists, who, much to their frustration, refused to disavow violence and, worse, refused to even work with each other. Meetings also took place with farmers, industrialists, professional bodies and trade unionists. All of them seemed to be completely united behind Smith and just wanted the British Government to let them get on with their lives.

The trip came to nothing. The British demands remained the same, that is, vague nonsense. Smith’s mind was as made up as ever and he chose to seek a fresh mandate to solidify his rule. The voting took place on the 7th of May and the Rhodesian Front swept all fifty ‘A’ roll seats (higher voting qualifications, purely economic and literary), an absolutely unheard of success. Thirteen of the fifteen ‘B’ roll seats (lower voting qualifications, essentially a concession to Africans) went to Africans, one went to an Asian and another to a Jew.

Talks continued from a distance, but no progress was being made even though Smith remarked in June that: ‘We are nearer now than we have ever been towards getting something concrete from the British Government.’60 Smith was under the impression that just some kind of African blocking mechanism would do the trick, but he was quickly dispelled of these illusions.

Smith, too, had matters which he wished to make the British aware of. On the 11th of June Smith wrote to Wilson, saying he wanted to inform Wilson of moves against Rhodesia by other members of the Commonwealth. All of the information which the Rhodesians had acquired was passed along to British intelligence. A memorandum was enclosed entitled Activities and Training of Rhodesian Subversives based upon the information gathered from 30 captured Nationalist terrorists which had crossed the Zambezi for paramilitary training. Ghana was funding the training and the training was taking place in Tanzania by Chinese instructors. Evidence was also provided of Nigerian dissidents being trained in Ghana, too. Smith wrote of his hopes that Wilson would express his open disapproval of these activities which very clearly went against the spirit of the Commonwealth.61

That June also saw the Commonwealth Prime Ministers Conference where, once again, ‘Rhodesia was the main theme’62. Once more the non-White nations of the Commonwealth (whilst the old, White, Dominions were sympathetic but refused to die on the Rhodesian hill so towed the line) demanded nothing less than the complete destruction of Rhodesia. Smith, whilst enraged, given that discussion of internal affairs of nations without representatives was forbidden, wrote to Wilson and let him know that he was ‘willing at all times to receive suggestions from you and to listen to what the British Government has to say on Rhodesia, but, frankly, I am not interested in what the other members of the Commonwealth say about our affairs, and what they do say will not turn us from what we consider to be the right thing to do in the interests of our country.’63

July saw a visit to Rhodesia from Minister of State for Commonwealth Relations Cledwyn Hughes and Smith offered a concession in the form of a senate in which blacks might wield the all important constitutional blocking mechanism. Alternatively, Smith offered, the ‘Africans in the Legislative Assembly should have a blocking quarter of the seats.’64 If this didn’t work, then what would, Smith asked. No reply was forthcoming and ‘this silence of the British Government encouraged Smith’s suspicion that there was no real intention to grant Rhodesia independence’.65 Another waste of time, the British simply could not announce what it was that they actually wanted besides the following five vague principles:

‘The Principle and intention of unimpeded progress to majority rule, already enshrined in the 1961 Constitution, would have to be guaranteed and maintained.

There would have to be guarantees against retrogressive amendment of the Constitution.

There would have to be immediate improvement in the political status of the African population.

There would have to be progress towards ending racial discrimination.

The British Government would need to be satisfied that any basis proposed for independence was acceptable to the people of Rhodesia as a whole.’66

When asked to suggest ways to actually implement these points the Rhodesian High Commissioner in London, Andrew Skeen, was simply told no.67 The British didn’t care, either, when they were told that all of these points were already enshrined in the 1961 Constitution which they, themselves, had helped to create. The times had changed, they said, by which they meant they wanted something even more anti-White to hand back to the non-White Commonwealth nations. Further concessions were needed, the British said, yet they never specified which kind.

The severity of the situation and the Rhodesian’s determination seemed to be completely lost on the British. When Andrew Skeen arrived in London to take up his post as High Commissioner he noticed that ‘the British politicians and officials, even those sympathetic to our cause, had not realised the depth of disillusionment that existed at that moment in Rhodesia regarding British intentions. Nor had they realised that the Rhodesian Front had ceased to be a political party and had become a national movement, of which Mr. Smith was not only the leader but its incarnation.’68 The British were under the bizarre impression that Smith was ‘manipulated by a junta of wealthy tobacco farmers’69 or some kind of extremists. Skeen took ‘great pleasure in informing them that there was no extremists or moderates in the party or the country, but that all were Rhodesians and all had the utmost confidence in their Prime Minister whose thinking and theirs were in complete accord’.70

Of the Rhodesian’s determination Skeen continued:

‘We had witnessed the process of handing over power rapidly to immature and often vicious demagogues in the African countries to the north of us – a process by which constitution after constitution was agreed upon and then discarded to the fetish of majority rule, regardless of whether such majority rule was in the interests of the majority itself. The time had come to make a stand against this, and this stand was what I was intended to demonstrate in London.’71

The eleventh hour was fast approaching. Smith would remark to the Rhodesian Front congress that the British would not possibly find any concession that would please the Afro-Asian bloc before stating his intention to leave the Commonwealth if the organisation was going to ‘continue embracing countries which are openly Communist and prepared to train saboteurs to come back here and sabotage a fellow Commonwealth country.’72

By now even those who would be most hit by the sanctions that would inevitably follow UDI were getting behind the cause. Tobacco farmers who would be worst hit by the trade embargoes and businessmen who would lose all their trade with Zambia were willing to put their short term personal interests aside for the greater good. Anything was better than the status quo. Repeatedly Smith would raise the ‘damaging impact of uncertainty’73 in his talks with Wilson and urge that a decision must be reached. Meanwhile Arthur Bottomley put his foot in it in Ghana by declaring that Britain would never grant independence to Rhodesia unless majority rule was granted.

A meeting was offered, but, clearly, Smith was at the end of his tether, replaying that:

‘I cannot go on much longer leaving the people of Rhodesia and the future of Rhodesia hanging in suspense.’74

The Eleventh Hour

Smith arrived in London on the 5th of October with his team. First up there was the meeting between the Rhodesian and British delegations minus Wilson. Here, once again, the five principles were restated but the British had no ideas regarding how to implement any of them. The Rhodesians offered a blocking third or quarter in Parliament as well as an Upper House of Chiefs and notabilities nominated by the Chiefs’ Council and other organisations. This was denied because ‘these hereditary noblemen were, to a man, paid by the Rhodesian Government.’75 After a break for lunch the Rhodesians offered to open up the B roll to universal suffrage, whereupon the British quickly moved onto the matter of racial discrimination, this amounted to a jumble of words which sounded nice to them but ultimately they were speaking ‘behind a smoke screen of ideology which has not proved practical anywhere on earth’.76 The day’s discussion came to nothing.

Zoomer HistorianRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1