Panics, Politics, & Power: America’s 3 Experiments With Central Banks

Authored by Andrew Moran via The Epoch Times,

The Federal Reserve, established more than a century ago, is the United States’ third experiment with central banking.

For much of its existence, the institution maintained a low public profile.

Only after the 2008 global financial crisis did the Fed begin communicating more openly, introducing post-meeting press conferences and allowing monetary policymakers to engage more frequently with the media.

Greater transparency, however, has brought greater scrutiny.

Public sentiment toward the Fed and its leadership has fluctuated over the years. Today, YouGov polling suggests the central bank is viewed favorably by 44 percent of Americans and unfavorably by 18 percent.

If the Fed pursues a series of reforms, it will have “another great 100 years,” said Kevin Warsh, who was nominated by President Donald Trump to serve as the institution’s next chair.

Comparable to past central banks, Warsh said, the current Federal Reserve System is beginning to lose the consent of the governed.

“You can think about the Jacksonians of prior times say that the central bank seems like they’re trying to focus and they’re all preoccupied with those special interests on the East Coast, and they’ve lost track of what’s happening to us in the center of the country,” Warsh said in a July 2025 interview with the Hoover Institution’s Peter Robinson.

“It’s a version of what worries me today.”

What happened in the past, and why is it relevant to today’s central bank?

The First Bank of the United States

In the aftermath of the American Revolution, the United States faced a series of immense economic disruptions, forcing the nation’s architects to rebuild the economy.

The objective was to lower inflation, restore the value of the nation’s currency, repay war debt, and revive the economy.

Alexander Hamilton, the first secretary of the Treasury under the new Constitution, proposed establishing a national bank modeled on the Bank of England. Hamilton stated that a U.S. version would perform various duties, including issuing paper money, serving as the government’s fiscal agent, and protecting public funds.

Not everyone shared Hamilton’s ebullience over a central bank.

Thomas Jefferson, for example, feared that such an institution would not serve the nation’s best interests. Additionally, Jefferson and other critics argued that the Constitution did not grant the government the authority to create these entities.

Nevertheless, Congress enacted legislation to establish the Bank of the United States. President George Washington then signed the bill in February 1791.

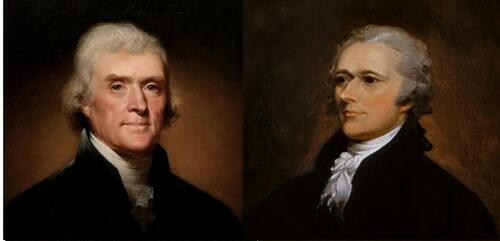

Two of America’s founding fathers: Thomas Jefferson (L) and Alexander Hamilton. The White House

While bank officials did not conduct monetary policy as modern central banks do, they did influence the supply of money and credit, as well as interest rates.

The entity managed the money supply by controlling when to redeem or retain state‑bank notes. If it sought to tighten credit, it would require payment in gold or silver, thereby draining state banks’ reserves and limiting their ability to issue new notes. If it wanted to expand credit, it simply held on to those notes, boosting state‑bank reserves and enabling them to lend more.

By 1811, the national bank’s charter expired.

While there had been discussions of allowing it to continue maintaining operations, Congress—both chambers—voted against renewing its mandate by a single vote.

Its closure came shortly before the War of 1812, which fueled inflation and weakened the currency.

Second Bank of the United States

Lawmakers believed another central bank was critical at a time of fiscal, inflationary, and trade pressures.

Congress used a similar 20-year model to produce the Second Bank of the United States, headed by Nicholas Biddle. The second incarnation had a federal charter, was privately owned, and was tasked with regulating state banks (with gold and silver for note redemption).

President James Madison, who opposed the first central bank on constitutional grounds, supported the new institution out of financial necessity.

Its creation stabilized credit and brought down inflation. However, by the 1830s, the bank faced strong opposition, particularly from President Andrew Jackson.

Labeled the Bank War, Jackson engaged in a years-long initiative to dissolve the central bank.

Jackson claimed the national bank was a tool for the wealthy eastern elite and a threat to self-government.

“The Jacksonians described themselves as conscious hard-money men who supported the rigid discipline of the gold standard, yet they opposed the newly powerful national Bank because it restrained the expansion of credit and, thus, thwarted robust economic expansion,” author William Greider wrote in “Secrets of the Temple.”

In 1832, Jackson vetoed legislation to recharter the bank four years early, delivering a fiery message that historians say was one of the most important vetoes in the nation’s history.

“It is to be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes. Distinctions in society will always exist under every just government,” Jackson wrote.

“There are no necessary evils in government. Its evils exist only in its abuses. If it would confine itself to equal protection, and, as Heaven does its rains, shower its favors alike on the high and the low, the rich and the poor, it would be an unqualified blessing. In the act before me, there seems to be a wide and unnecessary departure from these just principles.”

The charter expired in 1836, leading to the panic of 1837.

An economic crisis unfolded, leading to bank failures, business bankruptcies, rising unemployment, and contracting credit. While the collapse of the central bank is often considered a leading cause, the British also urged London banks to reduce credit to American merchants, causing a sharp drop in global trade.

As the smoke cleared and dust settled, it was not until the 1840s that the United States embarked on a historic economic recovery, now known as the Free Banking Era.

Banking was decentralized, and finance was largely unregulated. Despite an erratic financial system, the U.S. economy grew rapidly: agricultural production accelerated, railroads were built, and the country expanded westward. Additionally, deflation was paramount throughout most of the economic expansion.

The Federal Reserve System

The panic of 1907 led to the creation of the Federal Reserve System.

Following years of heavy borrowing, speculative commodities investments (mainly copper), and enormous stock market gains, a financial crisis was brewing. The event nearly brought down the U.S. banking system.

J.P. Morgan, a financier, intervened and emulated the actions of modern central banks. He met with the nation’s top bankers, facilitated emergency loans to financial institutions, and backed stockbrokers. The damage had been done as the United States fell into a year-long recession, marked by high unemployment and widespread bank failures.

The Federal Reserve Board of Governors seal in Washington on Oct. 29, 2025. Madalina Kilroy/The Epoch Times

Washington realized that it could not rely on private bailouts to prevent sharp downturns.

Sen. Nelson Aldrich (R-R.I.) is widely regarded as one of the chief architects of the modern Federal Reserve System.

In 1910, Aldrich hosted the famous Jekyll Island meetings, a gathering of U.S. officials and bankers, to discuss the blueprint of a new central bank.

While the initial draft laid the foundation for the institution, the official Federal Reserve Act was drafted by President Woodrow Wilson, Rep. Carter Glass (D-Va.), and H. Parker Willis, an economist on the House Banking Committee.

The new system was a public-private hybrid, with the federal government firmly in charge, and bankers running the regional reserve banks.

“It was Wilson’s great compromise,” wrote Greider, “creating a hybrid institution that mixed private and public control, an approach without precedent at the time.”

The legislation triggered a contentious political debate over the extent of its independence from the Treasury and the degree of authority delegated to policymakers over currency issuance.

Days before Christmas, the bill cleared both chambers and was signed into law by Wilson on Dec. 23.

“Wilson’s conviction that he had struck the right moderate balance seemed confirmed, however, by the reactions to his legislation,” Greider noted.

“It was attacked by both extremes—the ‘radicals’ from the Populist states and the bankers in Wall Street and elsewhere.”

Since its inception in 1913, the modern Federal Reserve has undergone numerous changes and has gained greater power.

The New Deal, for instance, allowed the Fed to become the lender of last resort as Washington learned the central bank could not prevent bank failures.

In 1951, the Treasury-Fed Accord restored central bank independence after the Federal Reserve had been forced to keep interest rates artificially low throughout the Second World War.

Congress then enacted the Federal Reserve Reform Act in 1977, establishing the dual mandate of promoting maximum employment and maintaining price stability.

2026 and Beyond

Over the past 50 years, the Fed has undergone modest changes, including the issuance of forward guidance and the disclosure of emergency lending facilities.

But while each new regime has nibbled around the edges, Warsh has suggested he could effect substantial reforms at the central bank.

“Until there’s regime change at the Fed and new people running the Fed, a new operating framework, they’re stuck with their old mistakes,” Warsh told Fox Business Network in October 2025.

“Bygones aren’t just bygones.”

Tyler Durden

Wed, 02/18/2026 – 16:20ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1