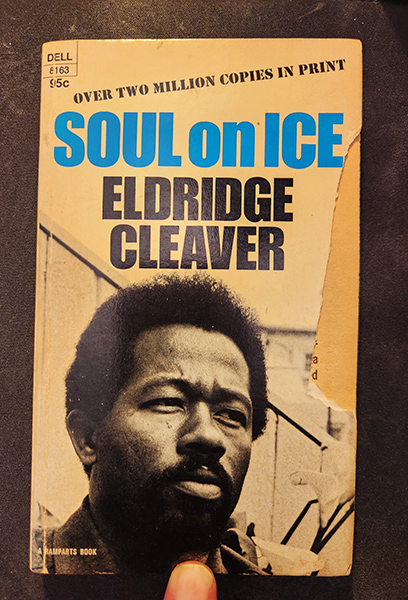

In the late 1960s, just about every young American knew about or had read Soul on Ice. It was touted as the authentic voice of righteous black fury, written by a man who had all the credentials a hippie could ask for. Eldridge Cleaver was a high-school-dropout convict who educated himself in prison, poured out his tortured soul behind bars, and burst onto the scene with a best-seller that quickly sold millions of copies. Many years ago, I picked up an old, damaged copy but never read it. Until now.

I wanted to see what was “radical” back when we still talked about “Negroes.” White critics raved about Soul on Ice, just as they rave about today’s black stars, such as Ta-Nehisi Coates or Ibram Kendi. Have blacks learned anything? Have whites?

First, though, Soul on Ice is not the work of Eldridge Cleaver alone. His lawyer, Beverly Axelrod (1924–2002), is said to have heavily edited it, so you can never be sure whether you are reading Cleaver or Axelrod. There are, however, ideas that I can imagine coming only from the mind of a black man.

Cleaver was born in 1935 and his family moved to Watts, California, in 1946. He had barely started junior high when he was arrested for stealing a bicycle. There were also arrests for vandalism and selling marijuana — lots of marijuana — and he was sentenced to 2-1/2 years in Soledad State prison. That was in 1954; Cleaver was just 19. He got out in 1957 but was back in prison the same year, and he stayed until he was paroled in 1966 at age 31. He wrote most of Soul on Ice during nine years in Folsom State Prison.

Eldridge Cleaver in Soledad State Prison

The Ogre

There is an aspect of the book that reviewers touch on lightly, but I will give it more serious treatment because Cleaver took it very seriously. Just three pages into the book, he introduces The Ogre, which I warn you is not racism or the white man or even capitalism:

The Ogre possessed a tremendous and dreadful power over me, and I didn’t understand this power or why I was at its mercy. I tried to repudiate The Ogre, root it out of my heart as I had done God, Constitution, principles, morals, and values — but The Ogre had its claws buried in the core of my being and refused to let go. I fought frantically to be free but The Ogre only mocked me and sank its claws deeper into my soul. . . . I also knew that it was a race against time and that if I did not win, I would certainly be broken and destroyed. I, a black man, confronted The Ogre — the white woman.

Cleaver was desperately, hideously obsessed with the sexual power of white women. He discovered this during his first prison sentence, age 19 to 21. He put a pinup of a white woman on his cell wall. The warden took it down because pinups were against the rules. Cleaver said plenty of men had them. The warden said yes, that was so, and it would be OK if he put up a picture of a black woman.

Cleaver was thunderstruck. Did he really prefer white women? He asked fellow convicts and they freely agreed: “I don’t want nothing black but a Cadillac.” “If money was black I wouldn’t want none of it.”

Emmett Till, who had flirted with a white woman, was killed in 1955 while Cleaver was in prison, and he saw a newspaper photo of the woman, Carolyn Bryant:

I felt that little tension in the center of my chest I experienced when a woman appeals to me. . . . It was all unacceptable to me. I looked at the picture again and again, and in spite of everything and against my will and the hate I felt for the woman and all that she represented, she appealed to me. I flew into a rage at myself, at America, at white women, at the history that had placed those tensions of lust and desire in my chest.

Carolyn and Roy Bryant.

Cleaver even wrote a poem called “To a White Girl.” Here are some lines:

I hate you

Because you’re white.

Your white meat

Is nightmare food.

White is the skin of evil.

You’re my Moby Dick,

White Witch,

Symbol of the rope and hanging tree,

Of the burning cross.

Loving you thus

And hating you so,

My heart is torn in two . . .

Cleaver puts the following words into the mouth of an older black prisoner:

I love white women and hate black women. It’s just in me, so deep that I don’t even try to get it out of me anymore. I’d jump over ten nigger bitches just to get to one white woman. Ain’t no such thing as an ugly white woman. A white woman is beautiful even if she’s bald headed and only has one tooth. . . .

The white woman is more than a woman to me. . . She is like a goddess, a symbol. My love for her is religious and beyond fulfillment. I worship her. . . .

Sometimes I think that the way I feel about white women, I must have inherited from my father and his father and his father’s father — as far back as you can go into slavery. I must have inherited from all those black men part of my desire for the white woman, because I have more love for her than one man should have. Yes, I want all the white women that they wanted but were never able to get. . . .

When I off a nigger bitch, I close my eyes and concentrate real hard, and pretty soon I get to believing that I’m riding one of them bucking blondes. I tell you the truth, that’s the only way that I can bust my nuts with a black bitch.

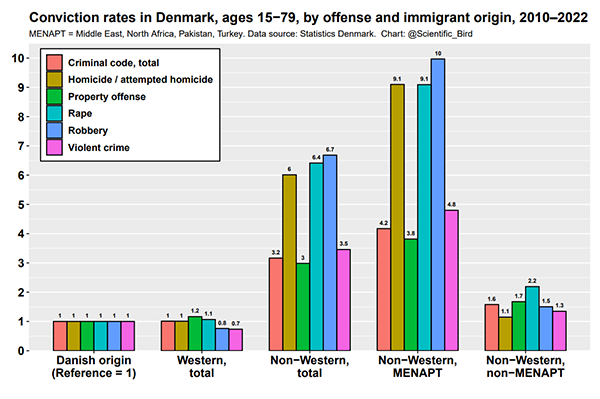

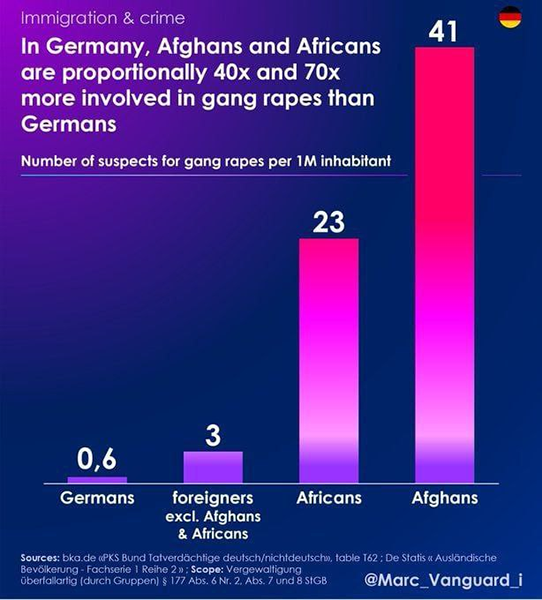

I don’t know how many non-whites are as tortured by their desire for the white goddess. If they are, they may be too ashamed to admit it. But what about the Africans and Muslims flooding into Europe? There is no end to stories about them raping and even murdering white women, and much as governments try to hide them, the statistics on racial assault (and other crimes) are staggering.

Cleaver decided to slake his desire and hatred by raping white women. First, he practiced on black women and then moved up to whites: “Rape was an insurrectionary act. It delighted me that I was defying and trampling upon the white man’s law, upon his system of values, and that I was defiling his women . . . .”

Cleaver quoted a poem called “The Dead Lecturer” by Leroy Jones:

Come up, black Dada nihilismus.

Rape the white girls.

Rape their fathers.

Cut the mother’s throats.

“I have lived those lines and I know that if I had not been apprehended I would have slit some white throats,” he wrote. “There are, of course, many young blacks out there right now who are slitting white throats and raping white girls.” These, he wrote, are “the funky facts of life.”

In a later chapter, Cleaver went into an extended fantasy about the effeminate white man and the white woman who has to make herself super-feminine so as to appear more feminine than the weak, pasty white man. The white woman gets no sexual satisfaction — only exhaustion — from the white man.

Cleaver imagined the black man as super-masculine and the object of the white woman’s fatal, secret desire. She longs for:

the thrust of his hips and the fiery steel of his rod. She is allured and tortured by the secret, intuitive knowledge that he, her psychic bridegroom, can blaze through the wall of her ice, plumb her psychic depths, melt the iceberg in her brain, detonate the bomb of her orgasm, and bring her sweet release.

Cleaver even wrote that the white woman/black man problem is something society must solve. “I think all of us, the entire nation, will be better off if we bring it all out front. A lot of people’s feelings will be hurt, but that is the price that must be paid.” I have no doubt what his idea of the “solution” would have been, and I’m sure he would be delighted by the images of black/white couples that flood advertising today.

But what about more respectable forms of black resentment? When Cleaver first went to jail in 1954, he had no politics, only instinctive hatred: “I turned away from America with horror, disgust and outrage.” “We [black convicts] cursed everything American — including baseball and hot dogs.” For him, the 1950s were a “Hot-Dog-and-Malted-Milk norm of the bloodless, square, superficial, faceless Sunday-Morning atmosphere that was suffocating the nation’s soul.”

Cleaver had a remarkable appetite for learning, and he spent countless hours in the prison library. He wrote that after his conviction for rape sent him to Folsom Prison for nine years, he spent every stint in solitary reading: Marx, Lenin, Russian anarchists, Machiavelli, Voltaire, Rousseau, Thomas Paine, W. E. B. Du Bois, Richard Wright, and Thomas Merton. The Communists convinced him that capitalism sucked the blood of whites and blacks alike, and this gave an intellectual sheen to his hatred for America. But its greatest crime was racism.

Cleaver was so impressed by a passage from Thomas Merton about Harlem that he copied it out and carried it with him like a talisman:

Here in this huge, dark, teeming slum, hundreds of thousands of Negroes are herded together like cattle, most of them with nothing to eat and nothing to do. . . . Inestimable natural gifts, wisdom, love, music, science, poetry are stamped down . . . , thousands upon thousands of souls are destroyed by vice and misery and degradation . . . .

What glories await the liberated black man! He wrote that “whenever I felt myself softening, relaxing, I had only to read that passage to become once more a rigid flame of indignation.”

What Cleaver wrote about “Negro convicts” is probably true today:

[R]ather than see themselves as criminals and perpetrators of misdeeds, [they] look upon themselves as prisoners of war, . . . [I]mprisonment is simply another form of the oppression which they’ve known all their lives. Negro inmates feel that they are being robbed, that it is “society” that owes them, that should be paying them a debt.

Cleaver sketched out alternatives for blacks, wondering “whether it is ultimately possible to live in the same territory with people who seem so disagreeable to live with; . . . others want to get as far away from ofays as possible. What we share in common is the desire to break the ofay’s power over us.” (“Ofay” has gone even farther out of style than “honky,” but it was a common slur for whites from the 1930s to the ’60s.)

Hatred and world revolution

“America has never truly been outraged by the murder of a black man, woman, or child,” he wrote, so black hatred is natural and inevitable. He quoted a fellow convict:

I’m thirsty for blood — white man’s blood. And when I drink I want to drink deeply, because I have a deep thirst to quench. I want to drink for every black man, woman, and child dragged to the slaughter from the shores of Africa, for every one of my brothers and sisters who suffered under the lash and the brand and the noose and the rape and the murder and the degradation and the humiliation and the insult and the injury inflicted upon us by the white man. Only the white man’s blood can wash away the pain I feel.

It’s no surprise that the only white man from American history Cleaver respected was John Brown, and that rebellious slaves were his heroes: “The embryonic spirit of kamikaze, real and alive, grows each day in the black man’s heart and there are dreams of Nat Turners legacy.”

And how’s this for an early version of “No justice, no peace”? “We shall have our manhood. We shall have it or the earth will be levelled by our attempts to gain it.”

Some of what Cleaver said is outmoded. He thought racism grew out of capitalism and that the two had to be destroyed together. A few silly people still say that, but one 1960s idea has just about disappeared: that black revolution is part of a world-wide, Third-World revolt against colonialism. Lefties still talk about “decolonizing” math and physics, but no one seems to think that the remaining scraps of empire — French territories of Mayotte or Guadeloupe, for example — have to free for American blacks to be free.

Here is Cleaver:

America’s support of colonialism must be shattered before the resources and administrative machinery of the nation can be freed to the task of creating a truly free and humanistic society here at home. It is at this point, at the juncture of foreign policy and domestic policy, that the Negro revolution becomes one with the world revolution.

American blacks were the revolutionary vanguard, fighting to undermine the most powerful capitalist nation: “The Negro revolution is the real bedrock,” and “it is not an overstatement to say that the destiny of the entire human race depends on the outcome of what is going on in America today.”

Cleaver predicted the end of history long before Francis Fukuyama: “This is the last act of the show. We are living in a time when the people of the world are making their final bid for full and complete freedom.” All who resist are “fascists,” and for them to prevail, they “must be prepared to unleash worldwide genocide, including the extermination of America’s Negroes.” Whew!

Hope

But Cleaver had hope. It started when he went back to prison for raping white women. Rape was wrong. It was taking the easy way out and running away from the problem: “The price of hating other human beings is loving oneself less.”

And there was hope even for white people, at least for the young ones who were on the right side of world revolution — the commies and draft-dodgers chanting, “Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh. The NLF [the Communist National Liberation Front] is going to win.”

“I am proud of them,” Cleaver wrote, “because they have reaffirmed my faith in humanity.” Young whites were as different from old whites as black radicals were from Uncle Toms: “The future rests with those whites and blacks who have liberated themselves from the master/slave syndrome. And those are to be found mainly among the youth.”

It is among the white youth of the world that the greatest change is taking place. It is they who are experiencing the great psychic pain of waking into consciousness to find their inherited heroes turned by events into villains. . . . Slave-catchers, slaveowners, murderers, butchers, invaders, oppressors.

Young whites understood that “the foundations of authority have been blasted to bits in America because the whole society has been indicted, tried, and convicted of injustice.” They have “discovered that America, far from helping the underdog, was up to its ears in the mud trying to hold the dog down.”

Here is more silly world-revolution stuff, but it echoes the white self-betrayal common today:

In the world revolution now underway, the initiative rests with people of color. That growing numbers of white youth are repudiating their heritage of blood and taking people of color as their heroes and models is a tribute not only to their insight but to the resilience of the human spirit.

The truth was devastating to whites but liberating for blacks:

When whites are forced to look honestly upon the objective proof of their deeds, the cement of mendacity holding white society together swiftly disintegrates. On the other hand, the core of the black world’s vision remains intact and in fact begins to expand and spread into the psychological territory vacated by the non-viable white lies.

Beverly Axelrod

There was an important figure in his life that gave him some respect for whites, and that was Beverly Axelrod, whom we saw earlier. She was a hard-left Jewish lawyer, 10 years older than he, who had represented radicals of every stripe. He wrote to her, asking for help on an appeal for parole. They met many times, and he wrote: “My lawyer is a rebel, a revolutionary who is alienated fundamentally from the status quo, probably with as great an intensity, conviction, and irretrievability as I am.” He wrote her love letters about how she made him feel:

My step, the tread of my stride, which was becoming tentative and uncertain, has begun to recover and take on a new definiteness, a confidence a boldness which makes me want to kick over a few tables. I may even swagger a little, and, as I read in a book somewhere, “push myself forward like a train.”

She wrote back:

I know you little and I know you much, but whichever way it goes, I accept you. Your manhood comes through in a thousand ways, rare and wonderful. . . . What an enormous amount of exploring we have to do! I feel as though I’m on the edge of a new world.

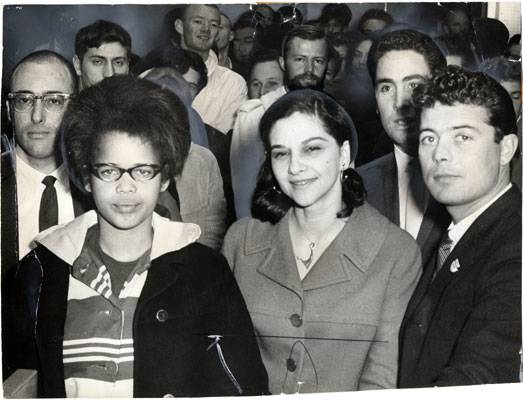

Beverly Axelrod, center.

Axelrod thought she had found true love: “If I had to pose naked on the middle of Broadway” for Cleaver, she wrote, “I would have done it.” She smuggled the manuscript out of prison, and some of his work appeared in Ramparts magazine while he was still in prison. When Cleaver next went before the parole board, he was already a published author with endorsements from writers such as Norman Mailer. He walked free in December 1966, with an agreement that he would pay Axelrod a quarter of the royalties.

They had plans to marry, and moved into an apartment together in San Francisco, but romance soured. When he introduced her to his mother, she asked why he wanted to marry an old white woman. He had decided to join the Black Panthers, and it wouldn’t do to have a white wife. He stiffed her on the royalties, which were considerable. She took him to court and got a judgement against him in 1971.

I think you now have a picture of the man on whom white critics lavished praise. The prominent critic and author Maxwell Geismar wrote in the book’s introduction that Cleaver was “simply one of the best cultural critics now writing . . . . He rakes our favorite prejudices with the savage claws of his prose until our wounds are bare, our psyche is exposed.”

After a review full of praise, the New York Times later decided Soul on Ice was one of the 10 best books of 1968, adding that it “indicates how the Negro revolution is already changing American values, white as well as black.”

Commentary called Cleaver “an immensely talented essayist, one of the best in America,” but struck a note of caution. Anyone who called him “ ‘a lousy writer’ would place himself in danger of being thought less than sympathetic to the militant struggle — than which, God knows, there are few worse things to be thought today in liberal circles.”

The New York Review of Books wrote: “Minds like Cleaver’s are sorely needed, minds that can fashion a literature which does not flaunt its culture but creates it.” What may be the most fawning praise came from Richard Gilman in The New Republic (March 9, 1968): Cleaver’s writing “remains in some profound sense not subject to correction or emendation or, most centrally, approval or rejection by those of us who are not blacks.”

Has anyone learned anything?

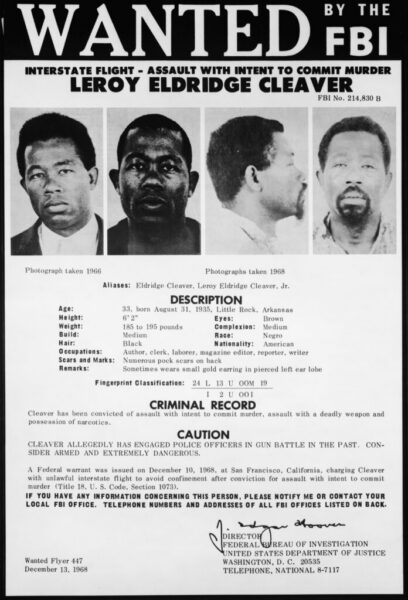

A little over a year after leaving prison on parole, Cleaver got into a shootout, which killed a 17-year-old Black Panther, Bobby Hutton, and left Cleaver and two policemen wounded. Years later, he admitted it was an unsuccessful ambush on police officers. Faced with revocation of parole, he fled the country and triumphantly toured nations then heralded as leaders of the world revolution — Cuba and North Korea — and then settled in revolutionary Algeria.

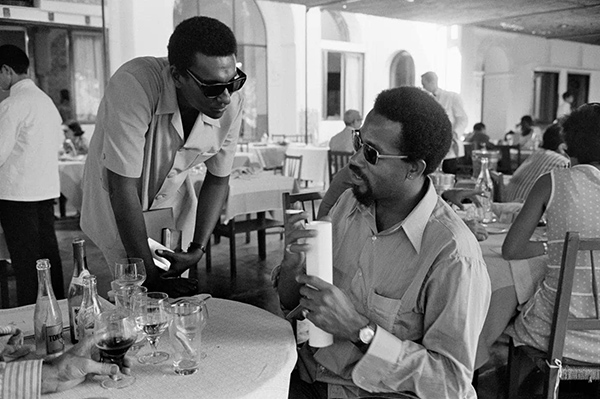

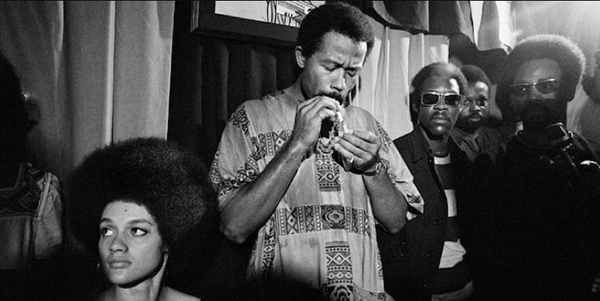

Stokely Carmichael, left, with Cleaver in Algeria.

The scales fell from his eyes: “I had heard so much rhetoric about their glorious leaders and their incredible revolutionary spirit that even to this very angry and disgruntled American, it was absurd and unreal.” After nine years in exile, he came home and surrendered to the FBI.

He got a spectacular plea deal: charges of attempted murder dropped in exchange for 1,200 hours of community service.

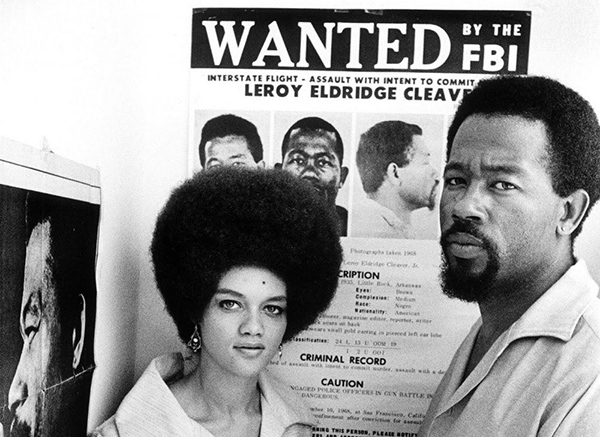

Eldridge Cleaver and his wife.

He became a born-again Christian, then briefly a Moonie, and was baptized as a Mormon in 1983 and attended LDS services until the end of his life. He declared himself a conservative and a Reagan supporter. In 1984, he demanded that the Berkeley City Council start its meetings with the Pledge of Allegiance, which it had abandoned years before. Mayor Gus Newport told him, “Shut up, Eldridge.” He died in 1998, age 62, living in obscurity, and was given a funeral at a Mormon chapel.

Cleaver had married a fellow Black Panther in 1967. She followed him into exile but divorced him in 1987 after he returned to the United States. In a 1994 interview, she said, “He came back a very unhealthy person, unhealthy mentally, and I don’t think he’s ever quite recovered. He became a profoundly disappointed and ultimately disoriented person.”

Cleaver and his wife in Algeria.

Unlike so many people, black or white, Cleaver learned that he had been wrong. Sadly, he never learned what to make of himself after that. He tried to write, but prison was the only place where he could shut out distractions, and once he lost his radicalism, he lost his writer’s voice. Maybe he needed a radical Jewish lawyer as his muse — or maybe nothing a sadder, wiser, former black radical could have written would have pleased anyone, black or white.

I wonder if the latest black messiahs will ever discover they were wrong. Ta-Nehisi Coates teaches at Howard University, no doubt thrilling black students with tales of black “bodies.” Ibram Kendi is also at Howard and has a new book coming out next month called Chain of Ideas: The Origins of Our Authoritarian Age. Believe it or not, it’s about how “the great replacement theory” has “brought humanity into this authoritarian age — and how we can free ourselves from it.”

As for whites, there will always be plenty of them thirsting to be told how awful they are, but they face a great replacement of their own.

The post Have Blacks Learned Anything? Have Whites? appeared first on American Renaissance.

American RenaissanceRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1