‘Where Do We Get Such Men?’

Authored by Jeff Minick via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

In the 1954 film “The Bridges at Toko-Ri,” based on James Michener’s novel and set during the Korean War, Adm. George Tarrant ponders the bravery of the Navy carrier pilots he commands, and then wonders aloud, “Where do we get such men?”

That same question occurs when we consider the life and death of Lt. Lance Sijan.

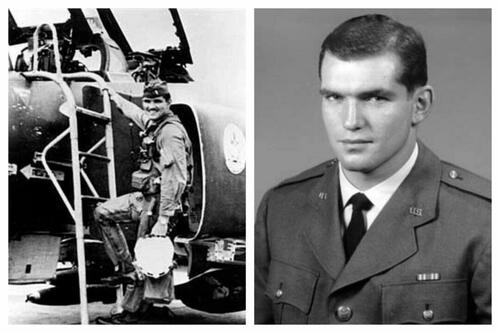

On Nov. 9, 1967, Sijan was flying as the backseat pilot of an F-4C fighter on a mission over North Vietnam when a malfunction in the timing fuse of a bomb enveloped the aircraft in flames. Sijan ejected into the night sky and fell into the triple-canopy jungle below, but the other pilot, Col. John Armstrong, went missing and was later presumed dead.

With no food and only a little water, and suffering from a broken leg, a fractured skull, and a damaged right hand, Sijan nonetheless evaded the North Vietnamese troops hunting him for the next 46 days. Even after his capture, he remained defiant, escaping at one point for a few hours, undergoing brutal torture, and finally dying of pneumonia.

The Man in the Making

When we look at Sijan’s background, we find only hints rather than firm reasons for his valiant attempt to escape his pursuers and the bravery he demonstrated during his torture, which was regarded with awe by his fellow prisoners.

Born and raised in Milwaukee, where his family owned and operated a restaurant, he and his younger sister, along with their immigrant parents, were active in the Serbian Orthodox Church. An outstanding high school athlete and student—he was an all-city football player and president of his school’s student government—he then entered the U.S. Air Force Academy, where he played varsity football for two years, and graduated in 1965.

Football would have offered Sijan lessons in endurance and courage, as did the rigid training at the Academy, which might have contributed to Sijan’s determination to resist capture despite his broken body. The military’s Code of Conduct for prisoners of war doubtless inspired him as well. Instituted in 1955 in response to the sometimes poor performances of POWs in the Korean War, the Code mandated that POWs resist the enemy as much as possible and make every effort to escape.

An Ordeal That Beggars Belief

Add all these factors together, however, and they don’t come close to explaining the source of his dauntless willpower in the jungle and in prison.

During those 46 days when he successfully hid from North Vietnamese troops, Sijan endured the vicissitudes of the weather and the terrain, all while suffering pain from his wounds. He was able to move by crawling or by lying on his back and pushing himself along. He ate plants, grubs, and insects, and drank by licking dew from grass when there was no rain and he couldn’t find a stream. When the enemy finally found him on Christmas Day, he was lying unconscious in a jungle road, rail-thin and wearing tattered clothing. He was three miles from his touchdown site.

That he had made this odyssey without a friend at his side or a word of encouragement from anyone only makes Sijan’s nightmarish trek even more extraordinary.

Unbroken

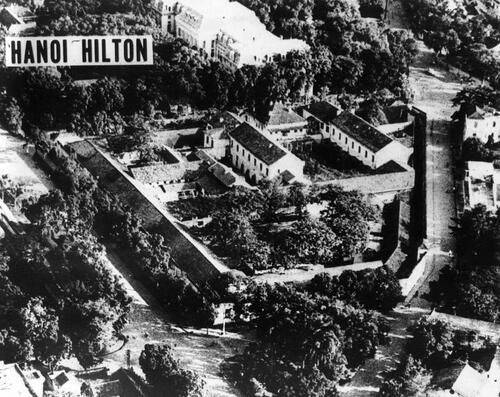

Two eyewitnesses later testified to Sijan’s heroism once captured. Capt. Guy Gruters, who had known Sijan at the Academy, and Maj. Robert Craner were also captives at the holding area known as “The Bamboo Prison.” He told them of his time in the jungle, and they observed firsthand the brutal torture of their wounded and sick comrade-at-arms in the enemy’s attempts to gain information. When the three men were transferred to Hoa Lo Prison, known to American captives as the Hanoi Hilton, Gruters and Craner bore witness to the continuance of Sijan’s vicious torture.

During these sessions, Sijan strictly adhered to the Code of Conduct and refused to give the enemy any information. Back in his cell, fed and assisted by his fellow prisoners, he continued to dream of escape.

On Jan. 22, 1968, Sijan died of pneumonia, abuse, and his jungle ordeal. Later, when U.S. authorities confirmed his death, he was posthumously promoted to captain and, in 1976, received the Medal of Honor. Part of the citation in that award reads: “During his intermittent periods of consciousness until his death, he never complained of his physical condition and, on several occasions, spoke of future escape attempts. Capt. Sijan’s extraordinary heroism and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty at the cost of his life are in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Air Force and reflect great credit upon himself and the U.S. Armed Forces.”

The Air Force Academy marked Sijan’s heroism—he was the first Academy graduate to receive the nation’s highest military honor—by naming a building after him, Sijan Hall. More importantly, fourth-classmen (freshmen) are required to know his story in detail. Established in 1981, the Lance P. Sijan USAF Leadership Award recognizes Air Force personnel who have exhibited the highest standards of leadership and character in their duties and in their personal lives.

If we return to Adm. Tarrant’s “Where do we get such men?” the answer remains elusive. Courage of this magnitude struck even his fellow prisoners as superhuman, a mystery beyond human explanation. What we must hope for, however, is that men and women possessed of such tremendous character continue to appear in our country’s time of need.

What arts and culture topics would you like us to cover? Please email ideas or feedback to features@epochtimes.nyc.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 10/16/2025 – 20:05ZeroHedge NewsRead More

T1

T1