How Germ Theory Sparked The Sanitary Revolution… And Life Expectancy Skyrocketed

Before germ theory gained acceptance in the late 1800s, doctors had little understanding of how diseases spread. Epidemics of cholera, typhus, and other communicable diseases were common—especially in overcrowded, unsanitary industrial cities, according to a fascinating new piece from History.

From 1850 to 1880, U.S. life expectancy at birth hovered around 40 years, dipping during the Civil War. But this figure was heavily skewed by high child mortality, says S. Jay Olshansky, professor of public health at the University of Illinois Chicago. Roughly 30 to 40 percent of American children died before age five.

“In the mid-19th century, human mortality was basically in the grip of natural forces,” says Samuel Preston, emeritus sociology professor at the University of Pennsylvania. Medicine offered “little gain,” apart from the smallpox vaccine, which became widespread by the 1840s and 1850s. Child mortality was far higher in cities and among the Black population than among white people, he notes.

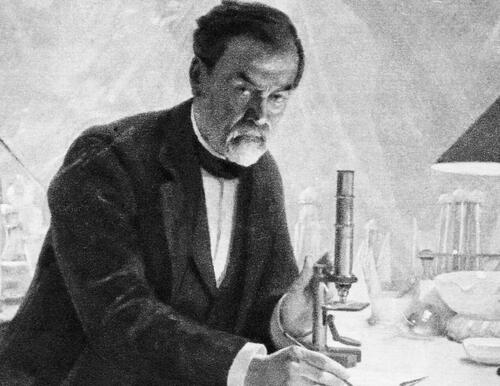

The History article details that diseases like tuberculosis and pneumonia were rampant. The prevailing miasma theory blamed foul odors and polluted air—until Louis Pasteur’s 1861 germ theory findings revealed that microorganisms caused disease. Acceptance of this idea by the late 1800s marked the dawn of the Sanitary Revolution.

With new insight into bacterial contamination, cities began transforming water and waste systems, says Michael Haines, economics professor at Colgate University. Water filtration, sewage regulation, and indoor plumbing spread rapidly. By 1902, most New York City neighborhoods had sewer service, and innovations like refrigeration and gas stoves improved food safety.

“Boiling of water and milk was a practice that was unknown until the 1890s,” Preston says. “Handwashing was promoted. Isolating sick patients in households was promoted. There was tremendous enthusiasm.”

Medicine advanced alongside sanitation. The 1890s diphtheria antitoxin became the first effective treatment for a deadly childhood disease, and vaccines for others soon followed. Early 20th-century reforms standardized U.S. medical education, closing low-quality proprietary schools.

“It was [addressing] some of these basic public health issues, combined with medicine, that had a pretty dramatic effect,” says Olshansky.

As parents learned to protect children from infection, deaths among the young plummeted—from about 347 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1880 to 180 per 1,000 by 1915, according to UN data. “Once we gained control over those early deaths … you start to see a dramatic increase in life expectancy,” Olshansky says.

By 1900, U.S. life expectancy had risen to 47 years; by 1950, it reached 68. The 1918 flu pandemic caused a brief dip, but gains continued as infectious diseases declined across all ages.

Haines calls this rise in longevity “one of the great achievements of the modern era.” Life expectancy approached 77 years by 2000 and reached 78.4 years in 2023, according to the CDC.

“Humans 140 to 150 years ago experienced this—subsequent generations, of course, benefitted from it,” Olshansky says. “But a quantum leap in life expectancy like that can only happen once.”

Read History’s full writeup here.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 10/23/2025 – 05:45ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1