How Long Does US Depositors’ Nerve Hold?

Authored by Tuomas Malinen via GnS Economics Newsletter,

I am returning to work slowly and will start with an update to the Bank Run Warning we issued on Friday.

Not a single financial institution sought funding through the SRF today (Wednesday), but this does not lead me to conclude that the risk of a banking crisis in the U.S. has passed. It just did not start right now.

While the borrowing from the Standing Repo Facility of the Fed has eased, for now, it does not indicate that the cash-drought some financial institutions are experiencing will be over.

The banks could have sought funding from other counterparties of the repo, or the beginning of the month could have brought more cash in.

The problem the banks currently face, relating to the government shutdown, is two-fold:

-

Money is accumulating in the U.S. Treasury General Account, and

-

Loan delinquencies are likely to be mounting.

The former implies that money is not moving from the government to the accounts of some 1.4 million government employees. The latter implies that, as government employees are not getting paid, some of them are not paying back their loans (principal and/or interest) either. Both of these diminish cash flow to banks. Like we noted in the warning on Friday:

What makes the situation precarious is the fragility of banks, which we documented in the Black Swan Outlook.

There has been a massive increase in bank lending during the past few quarters.

It is possible (likely) that some banks have been overly optimistic in the credit boom and are suddenly cash-starved because interest payments and loan repayments have ceased (from their excessive lending).

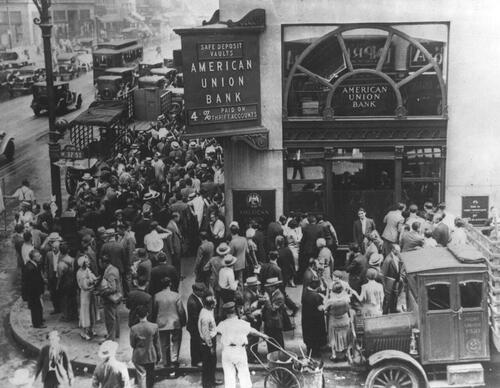

This may start rumors about the survivability of a bank or a group of banks, which could trigger a bank run in the current uncertain environment.

If there’s no shock, we can assume that the banking system keeps on functioning normally, ensured, for example, by the SRF, from which banks can obtain short-term liquidity to cover for deposit withdrawals.

However, banks are always at risk of failing due to the business model we want them to have. That is, we want to deposit our money in the bank and have it provide loans at the lowest possible interest rate for us. We also want instant access to our funds (demand deposits) or, alternatively, a higher yield (interest rate) to compensate for the lack of immediate access, like in savings accounts.

A standard commercial bank is a business that receives deposits and covers them with assets to balance its balance sheet (most U.S. regional banks operate like this). These assets can be in the form of loans to households and businesses, corporate or government bonds, or central bank reserves. Therefore, if all or a very high share of deposits are withdrawn, there simply is no bank anymore. Its business model fails. This directly implies that if we lose trust in a bank, no amount of reserves can save it from failing.

For example, a slew of bad news broke the trust of depositors in the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in mid-March 2023, resulting in a cataclysmic run on 87% of its deposit base in just a few days. No amount of reserves (which the bank had plenty of) could have saved SVB from the devastating outflow of deposits impairing its balance sheet. Thus, the bank failed and was taken over by authorities.

When I understood the role the gargantuan increase of easily-withdrawable demand deposits played behind the runs on SVB and Signature Bank, I thought that a nationwide bank run would almost surely follow the failures of SVB and Signature Bank. However, authorities managed to return the trust to the regional banking system better than I thought (by throwing a proverbial kitchen sink at it). It reminded me of how difficult it is to anticipate the timing and length of bank runs, even though I had warned about the fragility of the U.S. banking system just three weeks before the runs started. But, while the runs were halted, the problems remained.

The fact is that the U.S. banking system has been “run-prone” since 2022 (after the gargantuan increase in demand deposits), and the cash-drought created by the government shutdown is making it worse every passing day.

Hence, the likelihood of a negative shock breaking the trust of U.S. depositors in one or more banks currently grows by the day.

I worry.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 11/05/2025 – 15:20ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1