See here a report on the first day of the trial, here for day two, and here for day three.

Most of day four was spent on the testimony of the defense’s expert witness, Dr. Amy Klinger.

Dr. Amy Klinger, expert witness for the defense

Dr. Klinger is a professor of educational administration at Ashland University in Ashland, Ohio, as well as a former principal and elementary school teacher. She is the author of Keeping Students Safe Every Day and is the co-founder of the non-profit Educator School Safety Network. She is a certified Department of Homeland Security instructor and has developed trainings for FEMA. She was paid $350 per hour to review records for this case, and her fee to appear in court is $500 per hour.

Dr. Amy Klinger, defense expert witness

When questioned by Dr. Ebony Parker’s defense attorney, Sandra Douglas, Dr. Klinger said that after reviewing the case, she did not believe that Dr. Parker had breached educational standards or showed indifference on the day of the shooting.

She said the responsibilities of an assistant principal include student discipline, but also staff relations, daily operations and management, and working with parents. She emphasized the “assist” part of the “assistant principal” title and said that it is “very much a collaborative role.” She also said, “No one is the sole person responsible for school safety. . . . Every person who is in that organization has roles and responsibilities related to safety.”

When dealing with a specific threat to school safety, Dr. Klinger said that the first thing an administrator needs to do is to establish the credibility of the threat, and this is a collaborative effort. “An administrator cannot be everywhere,” she said.

The defense’s strategy appeared to be to spread the blame around: blame the victim, blame the other teachers, and blame the guidance counselor, while minimizing Dr. Parker’s leadership role.

Dr. Klinger stated that administrators will rely on information from the people “closest to the event.” She said teachers are considered “first line responders” who “provide really important intelligence for an administration to evaluate the credibility.”

She explained Dr. Parker’s ineffectiveness on the day of the shooting by saying that school administrators should avoid overreacting so as not to get into a “boy who cried wolf” situation. She said that when analyzing a potential threat, plausibility is important to consider. This shooting by a first grader was unprecedented, so it wasn’t considered plausible until it happened.

Dr. Klinger discussed the role of Mrs. Kovac, the experienced teacher who notified Dr. Parker that six-year-old JT might be hiding a gun in his bookbag. She said, “When the student did not allow for the bookbag to be looked at, Mrs. Kovac did not call a lockdown. She did not remove the bookbag. She did not remove the student. She did not remove the other students.”

She said there had been past examples at Richneck Elementary when student behavior problems were managed by calling in the guidance counselor, Rolonzo Rawles, or by calling security. Dr. Klinger believed Miss Zwerner missed opportunities to ask for help.

On the day of the shooting, Mr. Rawles became involved when Mrs. West, a first-grade teacher, told him that JT had badly frightened another little boy by showing him a gun and threatening to shoot him. Mr. Rawles asked Dr. Parker if he could search JT’s pockets, but Dr. Parker told him not to; she wanted to wait until JT’s mother came to pick him up.

Dr. Klinger said Dr. Parker’s “cautious approach” was appropriate. She said that searching a child “is not something that any school administrator should enter into lightly. . . This is a six-year-old. A little kid. And we are going to just, at-will start doing body searches on kids? That’s not any kind of endeavor that anyone should do. Especially when they don’t have a good amount of intelligence or information that would support that.”

Dr. Klinger stated that neither Dr. Parker nor anyone else could have foreseen that JT would shoot Miss Zwerner that day.

Cross-examination of Dr. Klinger

Following is the give-and-take of the questioning by the plaintiff’s attorney, Kevin Biniazan. I have noted my own reactions on hearing the live testimony and displayed them in italics.

I have covered a number of trials for American Renaissance, including the trial of Kyle Rittenhouse, and I would say that Mr. Biniazan brought the same level of skill to civil litigation that Mark Richards, a Rittenhouse attorney, brought to criminal defense. He revealed that Dr. Klinger had to stretch logic to defend Dr. Parker’s inaction after she was informed that a first-grader might have a gun.

Kevin Biniazan, attorney for the plaintiff

First, Mr. Biniazan reminded Dr. Klinger that she had testified that teachers were the “first line responders.” He said that there was a second line, which was Dr. Ebony Parker.

Dr. Klinger agreed.

Dr. Klinger had talked about the need to get good information. Mr. Biniazan said, “Getting good information is a two-way street. You don’t think an assistant principal should just sit in her armchair and wait for people to tell her information, and then just decide what to do based on what they tell her, right?”

Dr. Klinger: “I don’t know that that’s what happened in this case.” She mentioned that Dr. Parker had broken up a fight between two students in the hallway that day. “I wouldn’t say that she never got out of her chair, because clearly, she provided assistance when it was asked for.”

Dr. Klinger maintained that it was a “reasonable expectation” that other staff would bring information to an assistant principal, and that she shouldn’t have to “go door-to-door” checking on everyone.

Mr. Biniazan: “Mrs. Kovac told Dr. Parker explicitly about a gun and about a specific student. True?”

Dr. Klinger did not answer yes or no and seemed to want to avoid calling the gun a “gun,” instead referring to it as a “weapon.”

Mr. Biniazan read from Dr. Parker’s written statement, which said, “Mrs. Kovac came to my office and reported that the students were saying the student, JT, had a gun in his bookbag.”

Later, Mr. Biniazan asked about the two girls from Miss Zwerner’s class who told Mrs. Kovac that JT had a gun. “At what point in the day did Dr. Parker leave her desk to go talk to Girl Number One?”

Dr. Klinger replied that Dr. Parker didn’t know the identity of these girls, because Mrs. Kovac hadn’t told her.

Mr. Biniazan: “You’ve never spoken to Dr. Parker, have you? When you’re trying to say what Dr. Parker knew or didn’t know, it’s conjecture. She’s never told you.”

Dr. Klinger admitted she had never spoken to Dr. Parker.

Mr. Biniazan: “So, Dr. Parker’s obligation there stops? Because she didn’t get good information, she can sit back? To address the possibility of a firearm, did Dr. Parker request any specific information from anybody? . . . Did she say, ‘Will you go and search the person?’ or ‘Will you go and talk to JT?’ Or ‘Why don’t I go and talk to JT?’ Did she request any specific information in order to make the decision of what to do about a possible firearm on campus?”

Dr. Klinger: “It would appear that that was a discussion that was had with Mrs. Kovac and also with Mr. Rawles.”

From the testimony, it seems that the result of those discussions was that Dr. Parker’s only decision was not to search JT.

Mr. Biniazan next reviewed the timeline of events on the day of the shooting. Dr. Parker first heard JT might have a gun in his bookbag at 12:20 p.m. Mr. Rawles asked if he could search JT’s pockets for a gun at 1:40 p.m. “That would mean that for about an hour, Dr. Parker was aware that there was a possibility that there was a firearm on campus at Richneck Elementary, true?”

Dr. Klinger: “Typically, students would not say ‘firearm.’ They would say ‘gun,’ meaning a squirt gun. A ‘gun’ meaning a Nerf gun.”

Mr. Biniazan noted that Dr. Parker’s own statement said “gun” — not “toy gun.”

The “foreseeability scale”

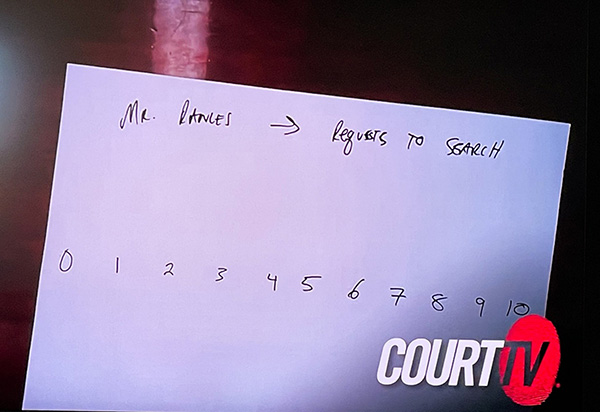

Next, in an almost theatrical moment, Mr. Biniazan showed Judge Matthew Hoffman a sheet of paper on which were written the numerals zero through tent, and asked if he could use it for “demonstrative purposes.”

The “foreseeability scale”

Judge Hoffman: “I’m not exactly clear where you’re going with that.” He nevertheless allowed it over the defense’s objection, to “see where he’s going.”

Mr. Biniazan: “January 6th, in the morning, before JT comes to school. . . What was the foreseeability of a gun on campus at Richneck Elementary School, on a scale of zero to ten?”

Dr. Klinger: “Probably a one.”

Mr. Biniazan: “It’s not like it’s off the radar, true?”

Dr. Klinger agreed but explained that the younger the age of the students, the lower the foreseeability would be.

Mr. Biniazan: “A firearm on campus isn’t just a risk of an active shooter, correct? There’s a risk of an accidental shooting.”

Dr. Klinger agreed.

Mr. Biniazan continued reviewing the events on the January 6 timeline each time someone brought information to Dr. Parker about JT’s gun, asking what the foreseeability would be at each point. “After Mrs. Kovac tells Dr. Parker that the two girls mentioned there was a gun, what is the scale of foreseeability?”

Dr. Klinger: “It’s higher than a one because you have that word that’s being used. But there also is the plausibility factor. . . . Unfortunately, there were no statements taken specifically from the students.”

Mr. Biniazan: “Dr. Parker didn’t take any statements from the students.” He asked about the moment that Mrs. Kovac said there was no gun in JT’s backpack, but that the boy had put something in this pocket.

Dr. Klinger raised the foreseeability at that point to “two or three” but maintained that age was a major factor in foreseeability. “A high school student most likely would have greater access to a gun, would have capabilities to use it. . . . [H]ow many six-year-olds have you seen walking around with a gun versus how many 17-year-olds have you heard of having a firearm?”

Mr. Biniazan: “We can talk about the CDC’s investigation into accidental shootings among elementary school students in 2023. Did you review that finding of the CDC?”

Dr. Klinger, evidently flustered: “For this case? No.”

Mr. Biniazan: “But you are aware, because you work with the Department of Homeland Security, that the CDC did perform an investigation into the prevalence of accidental shootings among minors, specifically children of the age of JT, correct?”

Dr. Klinger: “Aware of the study? I did not review it for this case. You were asking me questions not about an accidental shooting. You were asking me about foreseeability.”

Mr. Biniazan: “Foreseeability of a shooting on campus if there is a gun.” He then asked what would have been the foreseeability at the point when Mr. Rawles asked Dr. Parker if he could search JT’s pockets.

Dr. Klinger rated the foreseeability as “three” at that point but argued that the plausibility was still very low and that school administrators need to be cautious about conducting “a body search of a six-year-old.” She thought it was a good decision to search the child with “parent involvement.”

I had to wonder, why couldn’t someone, perhaps Mr. Rawles, have just ordered JT to remove his jacket? If he complied, they would not be searching his “person.” They would be searching a jacket.

Mr. Biniazan next asked Dr. Klinger to describe what would be an overreaction or an underreaction to a gun on campus.

After quibbling over the term “gun,” Dr. Klinger finally described what would have been an overreaction. “When a student says, ‘Student X has a gun.’ That we call a lockdown; we have an active shooter response. We search the kid. We put him down. We put him in cuffs. We drag him off until we can figure out that he had a Nerf gun or a squirt gun or a firearm.”

In this response, Dr. Klinger inadvertently made a list of actions that would have saved Abby Zwerner from being shot had Dr. Parker implemented any of them.

Mr. Biniazan: “So you agree that Miss Zwerner wasn’t expected to just drag the kid out of class, call a lockdown and do all this stuff? That would be an overreaction.”

Dr. Klinger, disagreeing: “It would be an overreaction to tackle the student. Get the police.”

Had someone called the police, perhaps Miss Zwerner would not have been shot.

Mr. Biniazan switched to the topic of underreaction. “An underreaction is an assistant principal not calling 911. True?”

Dr. Klinger: “Can I finish answering your previous question? A student can be removed from a classroom without being dragged, kicking and screaming. A student can be isolated; a bookbag can be moved, without it becoming an altercation or violent incident.”

Mr. Biniazan: “All things that Dr. Parker did not do. True?”

Dr. Klinger: “All things that Miss Zwerner did not do either. Or Mrs. Kovac didn’t do either. Or Mr. Rawles didn’t do either, because in their judgment, it was not an appropriate measure at that point.”

Mr. Biniazan: “Let’s answer my question. All things that Dr. Parker did not do. True?”

Dr. Klinger: “Yes.”

Sandra Douglas, attorney for the defense

On redirect, Dr. Parker’s defense attorney, Sandra Douglas, asked Dr. Klinger if her review of the case with Mr. Biniazan changed her opinions that she shared with the jury earlier.

Dr. Klinger: “No.”

Miss Douglas asked if any of the discussion where they circled numbers changed her opinions.

Dr. Klinger: “No.”

Miss Douglas made a good effort at damage control, but Mr. Biniazan’s line of questioning inspired me to think of all the actions that Dr. Parker could have taken to prevent the shooting but failed to take.

The next and final installment will cover the closing arguments and the verdict.

The post Zwerner vs. Parker, Day Four appeared first on American Renaissance.

American Renaissance

R1

R1

T1

T1