Don’t Fight The Fed… But Is China Worth A Shot?

By Daniel Moss, Bloomberg Markets Live reporter

The idea of taking out insurance against worst-case scenarios, mostly by cutting interest rates, became a popular choice among the world’s big central banks over the past quarter century. Beijing has shunned this doctrine lately. It may come with a price.

The People’s Bank of China recently downplayed concerns that the world’s second-largest economy is in trouble. The PBOC’s latest quarterly statement emphasized long-term prospects and discouraged investors from focusing on what it sees as merely short-term hurdles. Translation: Rein in those bets on rate cuts. Goldman Sachs was among those that got the message, pushing back its forecast for the next reduction to the first quarter of 2026. Other large institutions, including Citigroup Inc., had already thrown in the towel.

It’s natural that firms adjust projections to reflect what central banks are saying, as opposed to relying entirely on data for guidance. It has long been an article of faith in finance that you don’t fight the Federal Reserve. It has too much firepower and, if officials want markets to see things their way, they can jolt traders through words and deeds.

And while the PBOC can’t shake the global economy in quite the same way, and doesn’t have the same independence as the Fed, its sway is significant. If Beijing is hinting that it’s not inclined to crank up the expansion, it would be brave to dismiss that signal.

Would it be entirely wrong, though? Central banks do make mistakes, sometimes big ones. The Fed’s famous dot-plot projected four hikes in both 2015 and 2016. It delivered one in each of those years. The European Central Bank lifted borrowing costs shortly before Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. collapsed, and the PBOC itself botched an effort to revalue the yuan in 2015. And during the pandemic, the Reserve Bank of Australia vowed to control bond yields, until markets forced a capitulation.

China’s economy hasn’t fallen apart, but nor is it buoyant. After a solid start, progress has been disappointing. Industrial production has slowed, and investment has declined. Retail sales could be better. Exports unexpectedly shrank in October, and credit growth was the least in more than a year. Deflationary pressure persists. Bonds are sending a dour signal: The yield on China’s 10-year treasury is hovering near the lowest in two months.

Thanks to a decent first quarter, China will likely achieve the 5% annual growth target set by President Xi Jinping. That might discourage the need to act quickly to crank up the expansion, as might the desire to keep some ammunition in case the trade war with the US intensifies and takes a greater toll on the economy. Faced with a similarly tepid picture and anemic inflation, however, the Fed has a record of staying ahead of the curve.

Risk management — the practice of making policy a bit easier than might be justified by conditions — was pioneered by Alan Greenspan and deployed by each of his three successors. It was revolutionary when the Fed first began this approach in the late 1990s, and was used more forcefully in 2003 when officials were starting to get really worried about the prospect of deflation in the US. When the Fed cut rates in September, Chair Jerome Powell framed the step in a similar way. “The projections for growth this year and next actually ticked up just a little bit,” he told reporters. “What’s different is now you are see a very different picture of risks … it’s time to take that into account in our policy.”

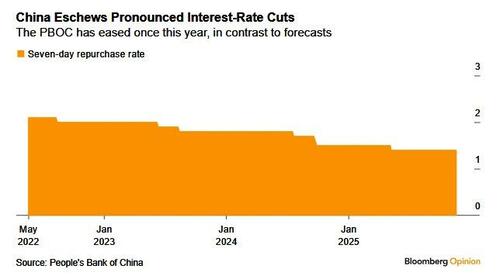

It has been a tough year for PBOC watchers. Twelve months ago, China’s leaders signaled active support for the economy. The decision-making Politburo, to which the People’s Bank ultimately answers, vowed to implement “moderately loose” policy in 2025. That was trumpeted as a marked shift from the “prudent” approach that dominated for more than a decade. Wall Street forecast a wave of rate cuts and a notable relaxation of reserve requirements at big lenders. That confidence proved wide of the mark. Instead of a pronounced easing, the PBOC delivered only a single 10-basis point trim to the main rate. That was in May; there’s been nothing since.

It’s true that monetary policy won’t solve all China’s ills. If PBOC chief Pan Gongsheng wants to go all out in a bid to banish deflation, it will likely require more than taking the price of money down a few notches. The seven-day repurchase rate, the main policy rate, stands at 1.4%. Once it gets below 1%, what happens next? The PBOC’s peers have found it difficult to extricate themselves from quantitative easing, and other unconventional measures. If Pan reckons the economy will muddle through, then hunkering down is understandable. It can also look indecisive.

The PBOC fancies itself as playing a long game. Let’s hope it’s right and the world economy, let alone China’s, doesn’t pay for an abundance of caution. Looking beyond the horizon has merit, but possesses its own dangers. Insurance shouldn’t be frowned upon.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 11/21/2025 – 10:05ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1