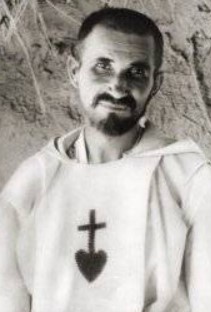

Saint Charles de Foucauld was only made a saint of the Roman Catholic Church twenty years ago in 2005 by Pope Benedict XVI and he is an interesting character to say the least having been a soldier and explorer as well as then giving it all up to become a Trappist monk only to then leave the order in 1897 and then left to live in Morocco among the Tuareg people – a large Berger ethnic group – there ‘to spread the gospel’.

The conventional picture of de Foucauld is provided ably enough by ‘Franciscan Media’ as follows:

‘When he declined to give her up, he was dismissed from the army. Still in Algeria when he left Mimi, Charles de Foucauld reenlisted in the army. Refused permission to make a scientific exploration of nearby Morocco, he resigned from the service. With the help of a Jewish rabbi, Charles disguised himself as a Jew and in 1883, began a one-year exploration that he recorded in a book that was well received.

Inspired by the Jews and Muslims whom he met, Charles de Foucauld resumed the practice of his Catholic faith when he returned to France in 1886. He joined a Trappist monastery in Ardeche, France, and later transferred to one in Akbes, Syria. Leaving the monastery in 1897, Charles worked as gardener and sacristan for the Poor Clare nuns in Nazareth and later in Jerusalem. In 1901, he returned to France and was ordained a priest.

Later that year Charles de Foucauld journeyed to Beni-Abbes, Morocco, intending to found a monastic religious community in North Africa that offered hospitality to Christians, Muslims, Jews, or people with no religion. He lived a peaceful, hidden life but attracted no companions.’ (1)

The problem with this picture is that it portrays de Foucauld as being implicitly philo-Semitic when in fact his choice of disguise as a jew was in order to explore Morocco was entirely driven by pragmatism and the reality on the ground in Morocco in 1883 as Fleming explains:

‘Foucauld was therefore to travel light. But in what guise was he to do so? He could not enter Morocco as a Christian: that would have meant death, for every Christian was considered a potential spy. Nor was the role of an apostate without risk: in 1880 an explorer named Oscar Lenz had travelled from Tangier to Timbuctoo posing as a convert to Islam, and on entering the Atlas had narrowly escaped being lynched. MacCarthy’s solution was that Foucauld should travel as a Jew. Jewish communities were scattered throughout North Africa, including Morocco, and their members visited each other regularly. They tended, too, to be paler-skinned than the Arabs and their religion was tolerated in Muslim communities. If Foucauld could find a holy man, a rabbi, to accompany him, and if he dressed appropriately, did not create a fuss and took notes in a surreptitious fashion, it was very possible that he might return from his mission alive.’ (2)

As it happens de Foucauld posed as one ‘Rabbi Joseph Aleman’ who was allegedly a ‘jewish doctor from Russia’ who had ‘recently fled the pogroms in his native land’ in order to explain both de Foucauld’s European appearance and why he was in Morocco in the first place. (3) Despite this de Foucauld still got stoned by the local Arabs because he was a jew (4) and even later as a Christian missionary in Morocco he was basically exploited to death by the local Arabs whom he regarded as ‘soup Christians.’ (5)

The point being that ‘Franciscan Media’ try to make de Foucauld out to be a kind of benevolent and clueless philo-Semite when de Foucauld was in truth anything but and while he did have deluded beliefs about how jews would be somehow ‘open to converting to the truth of Christianity’ early on these illusions quickly evaporated upon contact with reality. (6)

We only get glimpses of this in de Foucauld’s letters where while he writes in typically orthodox Catholic fashion in his essay ‘Meditations on the Gospel’ that:

‘Second, Our Lord uses two words of Holy Scriptures in speaking to his Father. We should use words of Scripture too since they come from the Holy Spirit, use them in our longer prayers, as the ancient Jews used to do and as the Church does, the spouse of Christ. We can use them too as ejaculatory prayers as Our Lord does here.’ (7)

This perspective is entirely orthodox and expected from a nineteenth century Catholic – and a general Christian – perspective as it represents normal Christian supersessionist theology, but we can see a tantalizing glimpse of de Foucauld’s violent anti-jewish and anti-Freemasonic views – common in France (especially in Catholic circles and particularly among the Catholic clergy) at the time – (8) in his letter to the Abbe Caron of 30th June 1909 where he wrote:

‘The early Christians would not let themselves be discouraged. And to us who have the life of the Church for eighteen centuries back to encourage us, efforts of Hell which Jesus said ‘should not prevail’ should seem very small and negligible. Neither the Jews nor the Freemasons can prevent the disciples of Jesus from working as the apostles did.’ (9)

This might seem mild at first but in truth the mildness is caused by de Foucauld’s point to Caron: the jews and the Freemasons cannot stop the apostles of Jesus working to ‘win souls for Christ’.

However, note that he also implies that jews and Freemasons are the forces/earthly foot soldiers of hell (and thus the devil) and we can quickly see that what de Foucauld is actually saying is that while Christian priests, missionaries and laity should not be stopped from spreading the ‘truth of the gospel’ by the activities and threats of jews and Freemasons; it doesn’t stop jews and Freemasons as the willing foot soldiers seeking to stop – i.e., slander, attack and even murder – them doing so.

Thus, we can see that what might seem a trivial or even neutral point is in fact not and suggests that de Foucauld was stridently anti-jewish and even potentially anti-Semitic.

References

(1) https://www.franciscanmedia.org/saint-of-the-day/saint-charles-de-foucauld/

(2) Fergus Fleming, 2003, ‘The Sword and the Cross: Two Men and an Empire of Sand’, 1st Edition, Grove Press: New York, p. 47

(3) Ibid., p. 49

(4) Ibid., p. 51

(5) Ibid., pp. 146-147

(6) Idem.

(7) Charlotte Balfour, 1930, ‘Meditations of a Hermit: The Spiritual Writings of Charles de Foucauld’, 1st Edition, Burns, Oates & Washbourne: London, p. 3

(8) Cf. Pierre Birnbaum, 1998, ‘The Anti-Semitic Moment: A Tour of France in 1898’, 1st Edition, University of Chicago Press also Paula Hyman, 1998, ‘The Jews of Modern France’, 1st Edition, University of California Press: Los Angeles, esp. 91-136

(9) Balfour, Op. Cit., p. 181

Karl’s SubstackRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1