“Regulatory Theater”: Meta Created ‘Playbook’ To Obscure Scam Ads From Regulators, Avoid Forced Verification

Last month Reuters revealed that roughly 10% of Meta’s annual revenue, or $16 billion, comes from advertising scams and banned goods – as the company only bans advertisers when its systems detect a 95% probability of fraud, while charging higher ad fees to suspicious buyers – a system critics describe as “pay to play.”

Data from fraud-reporting firm SafelyHQ shows Facebook is cited in 85% of scam reports that identify a platform, with more than 50,000 verified complaints collected so far, which CEO Patrick Quade suggests an implied victim count in the “tens of millions.”

Now, internal documents reviewed by Reuters indicate that Meta developed tools to both reduce scam advertising, and to limit regulators’ visibility into said ads after governments threatened measures that could severely cripple advertising revenue by forcing the company to reveal the identity of advertisers.

The efforts began last year after Japanese regulators highlighted a surge of scam advertising on Facebook and Instagram. The fraudulent ads included fake investment opportunities and artificial-intelligence-generated celebrity endorsements. Fearing that Japanese authorities might impose strict verification and transparency requirements that would materially affect its advertising business, the company launched an enforcement push aimed at reducing the number of fraudulent ads. At the same time, the documents show, the company focused on how those ads appeared to regulators.

The Ad Library and “Prevalence Perception”

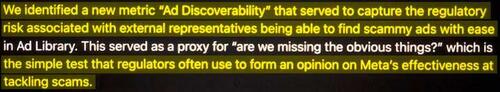

Meta’s remedy centered on its ‘Ad Library,’ a public database designed to allow users to search for ads running on Facebook and Instagram. Meta employees realized Japanese regulators were using keyword searches in the library as a simple measure of the company’s effectiveness at tackling scams.

To improve performance on that measure, Meta staff identified the keywords and celebrity names most frequently used by Japanese Ad Library users. They then repeatedly ran those searches themselves, deleting ads that appeared fraudulent from both the Ad Library and Meta’s platforms.

Internally, the documents describe this work as managing the “prevalence perception” of scams. The stated objective was to make problematic content “not findable” for “regulators, investigators and journalists.”

The tactic produced rapid results. Within weeks, Meta staff reported finding fewer than 100 scam ads in a week, followed by several consecutive days in which searches returned none. A Japanese legislator publicly praised the apparent improvement, and Japan ultimately did not impose the advertiser-verification rules Meta had feared.

From Local Response to Global Strategy

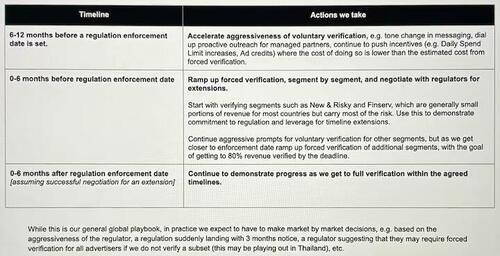

Given their success in dealing with Japan, Meta incorporated the approach into what internal documents describe as a “general global playbook” for responding to regulatory scrutiny worldwide. The same techniques – scrubbing Ad Library search results and reducing the discoverability of scams – were later deployed in markets including the United States, Europe, India, Australia, Brazil and Thailand.

This was all part of a broader strategy for delaying or weakening regulatory action, according to the report – with the playbook guiding Meta officials to offer voluntary measures, requesting time to assess their impact, and resisting universal advertiser verification unless laws leave no alternative.

Former Meta fraud investigator Sandeep Abraham, who left the company in 2023, said the approach distorts the transparency the Ad Library was meant to provide. Rather than offering an accurate view of advertising on Meta’s platforms, he said, it presents a curated picture optimized for regulatory review. Abraham described the tactic as “regulatory theater.”

Meta disputes that characterization. Company spokesman Andy Stone told Reuters that removing scam ads from the Ad Library is not misleading because the ads are removed from Meta’s systems overall. Fewer scams appearing in the library, he said, indicate fewer scams on the platform.

“To suggest otherwise is disingenuous,” Stone said.

Yet, the best solution would be costly – as Meta has long recognized that universal advertiser verification would significantly reduce scam activity. Internal analyses indicate the company could implement such a system globally in less than six weeks – yet the company has repeatedly balked at the cost. Executives estimated that universal verification would require roughly $2 billion to implement and could eliminate up to 4.8% of total revenue by blocking unverified advertisers. Despite generating $164.5 billion in revenue last year, nearly all from advertising, the company chose not to proceed.

Internal data show that unverified advertisers account for a disproportionate share of harm. One 2022 analysis found that 70% of newly active advertisers were promoting scams, illicit goods or low-quality products.

Instead of adopting verification, Meta chose what documents describe as a “reactive only” stance, accepting universal verification only where mandated by law.

Whack-a-Mole

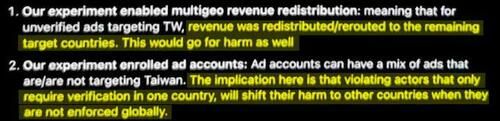

Despite Meta’s playbook, Taiwanese regulators dropped the hammer – threatening steep fines for unverified financial scam ads. Meta rushed to comply with new rules requiring advertiser verification, which authorities said coincided with dramatic reductions in investment and impersonation scams.

Meta’s own analyses, however, showed that much of the blocked fraudulent advertising was rerouted to users in other countries, displacing both revenue and consumer harm rather than eliminating it. Unless verification was enforced globally, staff warned, Meta would be relocating scams rather than eradicating them.

Even then, the documents show, the financial costs to Meta have remained small. Meta’s own tests showed verification immediately reduced scam ads in those countries by as much as 29%. But much of the lost revenue was recouped because the same blocked ads continued to run in other markets.

If an unverified advertiser is blocked from showing ads in Taiwan, for example, Meta will show those ads more frequently to users elsewhere, creating a whack-a-mole dynamic in which scam ads prohibited in one jurisdiction pop up in another. In the case of blocked ads in Taiwan, “revenue was redistributed/rerouted to the remaining target countries,” one March 2025 document said, adding that consumer injury gets displaced, too. “This would go for harm as well,” the document noted. -Reuters

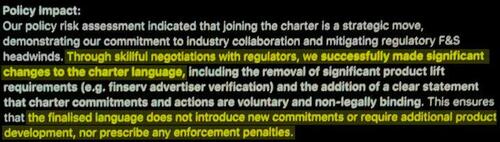

Hong Kong is another example – where Meta lobbyists moved quickly in 2024 to blunt a proposal by financial regulators that would have required verification of advertisers promoting investment products. To preempt stricter rules, Meta staff helped regulators draft a voluntary “anti-scam charter” and coordinated with Google to present what one lobbyist described internally as a “united front.” The final language, the documents note, imposed no new verification requirements or product changes. In an internal message celebrating the outcome, a Meta lobbyist wrote that regulators had relaxed measures that would have forced identity checks for financial advertisers, adding that officials expressed “huge appreciation” for Meta’s participation. Hong Kong regulators later said advertiser verification was only one of several tools available to platforms and emphasized that they lacked authority to mandate such requirements, while urging social media companies to do more to detect and remove fraudulent content.

In a statement, Hong Kong financial regulators said that “advertiser verification is one of many ways social media platforms can protect the investment public.”

In light of these findings, Meta has assigned scam handling its highest internal risk rating for 2025, citing regulatory, legal, reputational and financial exposure. One internal estimate warned that potential liability in Europe and Britain alone could cost as much as $9.3 billion.

Meanwhile, regulatory scrutiny has intensified – with European authorities having formally requested information about Meta’s handling of scam ads, and two U.S. senators urging federal agencies to investigate the company. The attorney general of the U.S. Virgin Islands has sued Meta, alleging it knowingly profited from fraud. Meta has said it strongly disagrees with the allegations.

For now, the documents suggest Meta believes its approach is working.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 12/31/2025 – 11:35ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1