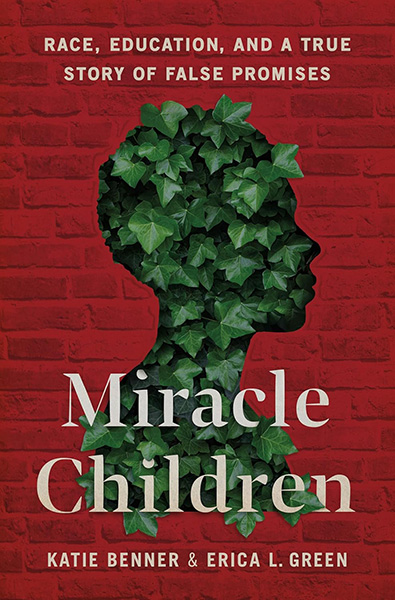

Katie Benner & Erica Green, Miracle Children: Race, Education, and a True Story of False Promises, Metropolitan Books, 2026, 272 pages, $27.95 hardcover

The T. M. Landry College Preparatory School in Breaux Bridge, Louisiana, started as a homeschool for just five children in 2005 but grew to serve over 100 mostly black students. It came to national attention in 2015 and 2016 by posting videos of its students learning of their acceptance at big-name universities. A video of Ayrton Little getting into Harvard and celebrating with his friends got 8,000,000 views on YouTube and was widely shared on Facebook and Twitter. Michelle Obama shared Ayrton’s post with the comment: “I am so proud of students all across the country who are getting accepted by their dream schools. These kids won’t let anything stand in their way!”

Ayrton and his Stanford-bound brother were featured on The Ellen DeGeneres Show. The hostess marveled: “So, this is incredible. You were raised by a single mom. You were on the verge of being homeless most of your lives. You spent years in a home with no heat and no food a lot of the time. And you’d leave the burners on to keep you warm at night. And through all of this you maintained the highest GPAs in your class.” The camera panned to the boys’ mother, seated in the audience, who smiled as the audience applauded.

Profiles of other Landry students were broadcast on The Today Show and CBS Morning News, and glowing reports appeared in print media. Landry was in one of the poorest counties in America, but it boasted a 100 percent graduation and college acceptance rate, with students getting into Yale, Princeton, Columbia, Dartmouth, and Brown.

In November 2018, journalists Katie Benner and Erica L. Green published an exposé in the New York Times. The school had falsified transcripts and invented student accomplishments. Some were said to have started nonexistent clubs for “survivors of abuse and addiction,” or to have excelled in imaginary classes in Mandarin Chinese.

Michael and Tracey Landry, the husband-and-wife founders, dictated application essays to students with perfect “up from hardship” stories guaranteed to appeal to white admissions officers. Ayrton Little and his brother, for example, had not spent most of their lives on the edge of starvation and homelessness. They had a hard time after their mother left their father, but by high school she was a chef and caterer, and drove an SUV. The brothers had transferred to Landry just one year before, from a well-known and expensive academy in Opelousas.

Miss Benner and Miss Green also wrote about the school’s disciplinary practices. In 2013 Michael Landry was sentenced to probation and an “anger management” program after pleading guilty to battering a student. According to interviews, “Students were forced to kneel on rice, rocks and hot pavement, and were choked, yelled at and berated.”

The school was mainly a boot camp for the ACT, and most classes were nothing but ACT practice drills. ACT scores were the one thing in college applications the school could not fake.

After the Times exposé, Louisiana State Police investigated the abuse allegations, and the FBI looked into the fake college admissions essays. The school shut down after 2021.

* * *

The authors of that original New York Times exposé now tell the full story of T. M. Landry College Preparatory School in their book Miracle Children.

Michael Landry was born in Breaux Bridge, Louisiana, in 1969. His father was a plumber with a reputation for “juggling multiple girlfriends” and fathering many children. Young Mike did not see much of him.

His was born to Barbara Landry, a teenager who lived in a corner of Breaux Bridge called “the back of the tracks.” It was poor, and the last whites moved out by the 1970s. Neighbors and relatives remember her as a heavy drinker who lived on food stamps and welfare. Mike spent a lot of time with his maternal grandparents in a nearby public housing project.

Michael Landry stayed out of trouble. “I loved school — going to school was this safe haven for me.” He did well enough to get into the University of Southwestern Louisiana in nearby Lafayette. He joined a black fraternity and had a reputation as a charismatic classmate, if only a mediocre student: As an adult, his notes and email were filled with grammatical and spelling mistakes. He had a lot of bluster, however, and convinced skeptical friends that he had graduated magna cum laude.

He fathered a child as a student, but failed to marry. After graduating with a business degree, he enlisted and served in the first Gulf War. After he got back, he met and married a girl named Mae from Atlanta.

People who knew Mr. Landry in this period recall that he dressed to impress, with suits in bright colors. He also liked to sport the ultimate black status symbol: the latest high-end sneakers. He talked of getting rich even though he was mired in credit card debt.

Mae recalls him going to take the brokerage exam at Dean Witter and returning the same evening with the implausible news that he had already been asked to start managing clients’ money: “Even if he had aced the exam, she found it odd that he would have no training period. ‘You don’t just get handed a lot of other people’s money’.” Some of Michael’s relatives warned Mae not to believe everything he said. Going through his papers, she found nothing from Dean Witter. She decided to pack her belongings and leave. They divorced in 1999.

Michael returned to Breaux Bridge, telling everyone of the riches he had supposedly made at Dean Witter. He soon reconnected with Tracey Johnson, a childhood neighbor, then working as a nurse. The couple married and adopted two children. Michael learned in 2005 that his son Marcus could barely read, even though he passed all his tests. School officials said that was all that mattered: “if your son is doing well on his tests, there is no problem.” The couple decided to withdraw Marcus and his younger sister from public school and teach them themselves.

Soon they were boasting to their neighbors that Marcus had completed two grade-levels of math in a single summer. Other families began asking the Landrys to take on their own children. They started “telling audiences that education was their calling. They knew there was greatness in the children whom society saw as nothing special.” By 2012, they had a dozen pupils, and taught school in a disused furniture store. Michael had students dress in sweater vests adorned with a school crest he had designed.

He did not encourage parental involvement. When parents asked him how he achieved all the results of which he boasted, he told them not to worry and not to talk to their children about education at all. He claimed he used “mastery learning techniques,” an expression that was common in the 1960s, but the Landrys were vague about what that was. Former students report that the school made heavy use of online classes provided by Khan Academy, an American non-profit organization that produces free learning resources. As the authors write: “T. M. Landry students paid between four and six hundred dollars a month in tuition . . . yet spent their days taking online classes they could have logged into at home” for free.

Most students had long periods of unsupervised and unstructured time. There was no set curriculum. A student’s grade level or course of study could change by the day, sometimes by the hour. How students spent their long school days depended mostly on Michael Landry’s mood. He called this “organized chaos,” and said it was a source of motivation, and a way of preparing graduates to outthink and outmaneuver their peers.

Serious effort and discipline were largely devoted to preparing students for the ACT, and the repetitive drilling could be brutal. One student recalled: “I was losing sleep because I was so worried about this test.” If Mike decided a student had underperformed, he would make him kneel as other children insulted him. Friends would turn against friends and even against family members. Some of the bullies may have feared they would be the next victim, and wanted to show loyalty to Mike.

In June 2012, a man noticed bruises on his 12-year-old grandson who attended Landry. The family contacted the Breaux Bridge Police Department. According to the Sheriff’s Office report, the boy complained that he thought there were rat feces on a fork at school. As his peers looked on, Mike pushed him to the floor, bruising him, and forced him to eat whatever was on the fork.

Once, when Mike suspected a pupil of playing video games during class time, he choked and slapped him, and stepped on his head as he lay on the floor. He whipped some students with his belt.

Louisiana had no authority to investigate the Landry School due to a legal relic left over from the fight against racial integration two generations earlier. State legislators had made it possible for segregated academies to operate without oversight as long as they did not seek state recognition or government funding. Some of the resulting “schools” turned out to be scams that existed only on paper. Landry’s largely black school avoided accountability by using this legal loophole. Most parents had no idea the school was unaccredited and not subject to oversight.

Michael Landry was convicted of simple battery and sentenced to one year’s probation, a $100 fine, and an “anger management” class, but he was free to keep running the school. A few students dropped out, but Mr. Landry was able to convince most parents that he had had permission from parents to administer punishment. Some later regretted ignoring what should have been a red flag, but explained to the authors that their doubts were overridden by an intense desire to see their children do well.

The Landrys were half a million dollars in debt despite a combined income of $135,000, mainly from tuition. They filed for bankruptcy, and were rescued in part by a generous donation from a retired NFL player who provided new premises where the school could operate rent-free.

2013 saw the first class graduate from T. M. Landry Prep. The Landrys bragged on Facebook and Twitter that one senior had been awarded $691,000 in scholarships to attend New York University. This ought to have roused suspicions, since annual tuition at NYU that year was less than $60,000.

During the 2013–2014 school year, Michael Landry began taking students to “college fairs” in New Orleans and developed contacts with admissions officers. That year. a Landry student was accepted at Brown University, and the school posted a crude celebratory video accompanied with the boast: “T. M. Landry College Prep makes it to the IVY LEAGUE!” More professionally produced videos would come later. A Brown admissions officer soon visited Breaux Bridge to see the Landry School for himself. He liked what he saw, and told his colleagues.

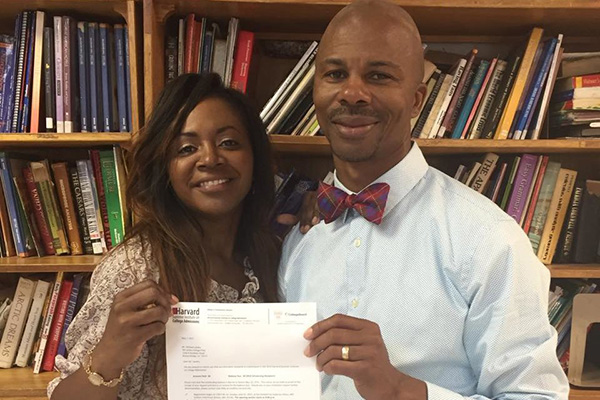

The following summer (2015), the Landrys were invited to attend the Harvard Summer Institute on College Admissions, where they made a splash: “The crowd loved listening to the Landrys talk about the lack of opportunity for poor black students in Louisiana. . . . At T. M. Landry, [they explained,] average students were transformed into math and computer science prodigies.” Michael and Tracey met with admissions officials from top schools.

Posting on Facebook after the event, they wrote: “This conference has earned T. M. Landry College Prep a prominent place in the minds of the movers and shakers of the best universities in the nation. . . . Michael and Tracey have formed relationships that will benefit their students for years to come.” This was impressive to folks back in Breaux Bridge, who came to believe their children’s future depended crucially on Michael Landry, who seemed to have important people in his back pocket.

In December 2015, T. M. Landry made its first viral video about a student being accepted at Harvard. However, this student transferred to Landry only in his senior year. This was part of a pattern: as word of the school’s success spread, students who were already succeeding elsewhere switched to Landry and continued to do well.

Tracey and Michael Landry holding a letter from Harvard.

Mike and Tracey told students not to socialize with children at other schools. Students who broke that rule got intensive interrogations about where they had been. Local Breaux Bridge teens started noticing that they stopped hearing from friends at Landry, and people began to suspect that something was wrong.

The authors interviewed a girl named Madison who visited the T. M. Landry School as a prospective student. She told Michael Landry she hoped to get into Columbia, and that her ACT score was (a very respectable) 33. He told her it needed to be 36 — a perfect score — and that the only way to get it there was to come to T. M. Landry.

What stunned her was his claim that he could produce the ACT score and transcript she would need to pass muster with the admission office. Madison knew that standardized tests were essentially impossible to game. Seeming to sense her skepticism, Mike pulled out a copy of the ACT. “I’ll make that into a thirty-six,” he said, as if he could just write it on the test. Even more troubling was his assertion that he would put whatever she needed on her transcript. [ . . . ] He said she would never get into Columbia without his help. “I have a direct in with these schools,” he insisted. “Only way you’ll get in is you come here.”

Madison noticed that Michael asked her very little about herself. She also noted the chaotic atmosphere of the school, with children running around unsupervised. She did not take the bait.

The Landrys sometimes invited parents to teach at the school, giving a few of them a very good look at what was going on. Kina Williams was a certified science instructor at a nearby public school. When she enrolled her own children at the Landry’s school, they loved it.

In the fall of 2016, when Mike recruited her to teach at the school, she could see why: “They [the children] didn’t have to do anything.” Within months, Kina noticed red flags. Students who posted high marks on the ACT couldn’t string sentences together. There were teenagers knocking the ACT math sections out of the park but adding and subtracting on their fingers. “It seemed like the longer they were at TML, the less they could perform.”

Outwardly, the school continued to thrive. In January 2017, it moved into an old factory building 10 times the size of its previous school. Within a few months, the student body grew from a few dozen to over 100, including a number of white students. These changes appear to have occurred with the advice and possibly the help of the Landrys’ friends “up north,” whom they had impressed at the Harvard Summer Institute. As the school’s reputation grew, journalists and other visitors became a regular sight. The Landrys now regularly posted professional-quality videos of students boasting of their ACT scores, college acceptance letters, and ambitious plans for the future.

Michael Landry assured his teachers that

they would soon be flying across the country, even oversees, consulting with families looking to get their children into Ivy League schools. They’d even open their own schools, following in his footsteps. “You’re going to make millions,” he said. “Y’all each going to run your own T. M. Landry.”

A school with over one hundred students cannot operate like the homeschool for five that the Landrys started in 2005. Well-wishers encouraged better financial record-keeping, rules and procedures, and a written syllabus, but with little success. In 2017, the school hired the mother of a student as an “administrative assistant and operations manager.” When the Landrys tried to pay her in cash, she set up accounting software, and started a regular payroll.

Michael Landry’s conviction did not cure him of excessive punishments. One day in 2017, he caught a boy named Nyjal Mitchell playing around with his friends when they were supposed to be studying:

No sooner had Nyjal scurried to sit down than Mike was at his back. Mike placed him in a chokehold and pulled him to the floor. Nyjal went limp, due partly to shock and partly in submission. Mike grabbed the hood of Nyjal’s sweatshirt and was dragging him across the concrete floor with it. When they came to a stop, Mike put his foot on Nyjal’s throat. He then made the boy kneel.

Nyjal did not tell his mother, but word eventually reached her that “something is not right with Nyjal.” When he admitted what had happened, she rushed to the school to confront Michael Landry. In the ensuing argument, the Landrys locked her out of the building. They then called an emergency meeting with about two dozen parents to present their version of events:

A parent was going to lodge a false accusation against him. The Mitchell family were out to extort him for money. He went around the room asking various students if anything had happened. Every one of them said no.

They were too worried about protecting their college prospects to admit the truth, and most of the parents were convinced. Michael Landry had ridden out another storm.

He was also pushing students to tell wild lies in their college application essays: tales filled with “drugs, death, hunger, poverty, abandonment, and violence — the kind of stories he said admissions officers loved.” He spun out examples for them to follow: “a black girl hiding under her bed while bullets flew outside her window; a black boy angry at his father for leaving him and his family homeless.” “If you don’t make me cry, it’s not good enough,” he told seniors. One aspiring musician claimed to have practiced the viola until her fingers bled and blistered. If students could not concoct acceptably pitiful tales, the Landrys would dictate them.

The resulting essays often slandered devoted parents for whom Landry tuition was a real sacrifice. Some students told the authors they felt little guilt about these fabrications because they were convinced the system was rigged against blacks: “It’s kind of like an eye-for-an-eye mentality,” acknowledged one.

With ever-increasing numbers of Landry students applying to elite colleges, Mike and Tracey began to lose track of the transcripts and credentials. They sometimes produced multiple transcripts for individual students, tailored for different colleges. One application was submitted to St. John’s in the names of two different students. A short essay answer sent to Princeton in 2017 was recycled and sent again in 2019.

Admissions officers at elite schools must process application essays at a rate of seven per hour, and many couldn’t imagine an entire school gaming the system.

At the graduation ceremony of 2017, Michael Landry claimed the senior class had been awarded over $20 million in scholarships. As the authors point out, that would amount to over $1.5 million per student, “a preposterous figure.” A student later told them: “In all honesty, I think we all knew he was fabricating a lot of things, but kind of chalked it up to his showmanship. He would use hyperbole so often that I think at a certain point everybody was numb to it.”

Adam Broussard had been an especially loyal supporter of the Landry School since his elder son Elijah was part of the first graduating class in 2013 and went to Brown. In the fall of 2017, he looked through a batch of assignments his younger son Collin had completed for Landry. He shook his head in disbelief: “The sentences were grammatically incorrect, their structure incoherent.” When confronted, Michael Landry assured him that all was well. The father had his son tested by Sylvan Learning Center. Collin, in his second month of third grade, was at a second-grade level in math and a first-grade level in English. In June 2018, Adam began telling other parents to get independent testing for their children. Word got out that one of Landry’s most loyal parents was on his way out. When Michael got wind of this, he expelled Collin.

Millions of people were now watching the school’s videos of students winning acceptance at top universities, and journalists poured in to cover T. M. Landry’s success. Before film crews arrived, Michael ordered that certain pupils be kept home for the day:

students with disabilities, the ones who could not perform on cue or whose families could not afford to keep them in bright white sneakers. The very children whom Mike said T. M. Landry had been created to serve were increasingly being sidelined and shunned.

Following the appearance of brothers Ayron and Alex Little on The Ellen Degeneres Show, contributions began pouring in from wealthy philanthropists and ordinary viewers. According to the school’s own records, it received a total of about a quarter of a million dollars, mostly earmarked for tuition. But people noticed that Michael and Tracey were starting to dress in designer clothes. Tracey got a new diamond ring.

Amid all this outward success, parents began following Adam Broussard’s advice to get their children tested by Sylvan. One learned that his seventh-grade daughter was performing at a fourth-grade level — the grade she had been in when she first enrolled at T. M. Landry. Some parents withdrew their children, while others decided to confront Michael Landry. At a tense meeting at the school, they asked him: “When are you going to start testing students?” “Why, every time I ask my son what he did at school, does he tell me ‘Nothing?’” “Are the diplomas even real?” After his usual bluster about nontraditional methods, he told them if they didn’t like the way he did things, they could leave.

Then he also added something that enraged the black parents: With white donors pouring thousands of dollars into the school and white children coming from across Louisiana to enroll, he was going to turn T. M. Landry into a white school! “This shocked the parents into silence — they had always felt bonded to the school by their loyalty to a black man helping their black children. They left, humiliated and ready for revenge.”

In the summer of 2018, students from the class of 2017 began returning from their first year of college. Many had done well, especially those who had only transferred to Landry toward the end of their school careers. But others had found that the rigorous math and science majors Mike had made them declare required much more than they had learned through ACT prep. They couldn’t keep up with their classmates. Some had fallen into depression. One dropped out after only two months. Some of these students also began to open up about the forced kneeling and other abuse at the Landry School.

The parents’ group got wind of these stories, and in October 2018, they got a lawyer:

When Ashlee McFarlane got the call in October 2018, she couldn’t believe what she was hearing. Like the rest of the world, she had enjoyed T. M. Landry’s viral videos. But she was a former prosecutor, and as she heard more from the parents, she smelled a scam. She decided to make the trip from Texas to meet with the parents and found herself surrounded by more than a dozen desperate families looking for recourse. The media had ignored them, and Mike had been trashing them all around town. McFarlane said she would help them gather information and share it with the FBI. But if they wanted immediate awareness and attention to their stories, the fastest way would be to engage the press. With the families’ approval, she picked up the phone and called a reporter at the New York Times.

This led directly to the authors’ exposé of the school published in the Times on November 30, 2018.

By January 2019, T. M. Landry was in free fall. The sheriff’s office decided to give Nyjal Mitchell’s case a fresh look, and more than a dozen people reported additional allegations of child abuse. Enrollment sank from a high of 110 students to about 60. National pressure ramped up, too, with the FBI scrutinizing the school for violations of federal law.

The worst was postponed when a local businessman was appointed to head the school’s board, with Michael and Tracey Landry staying on as teachers. But after graduation celebrations in 2021, the school appears to have closed down. The authors were unable to track down Michael and Tracey Landry.

* * *

For a brief season, the T. M. Landry College Preparatory School elicited widespread euphoria from a nation desperate to believe stories of blacks coming from nothing to scale the heights of American society, but it will survive only as a cautionary tale. Its seeming ability to discover or manufacture black prodigies was nothing but a con man’s talent for telling people what they want to hear. Things that sound too good to be true usually are.

The post The School That Minted Black Prodigies appeared first on American Renaissance.

American RenaissanceRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1