The White race in Europe and the Anglosphere faces extinction. Year by year more third world immigrants pour into our lands by ‘legal’ or illegal means, year by year they commit more crimes, year by year they leech off of us more and more brazenly. Quite naturally the response to all of this has been a widespread ‘awakening’ amongst the native White population, especially since the post-Covid years in which the floodgates were opened on a scale like never before. This phenomenon will only continue on an even greater scale and it is a process which simply cannot be stopped. Nationalism and Remigration are ideas whose times have come, as inevitable in hindsight one day as the Reformation or Enlightenment are to us now. Compare how extreme the average right winger was a few years ago versus today, the two positions are simply worlds apart. Soon enough, most Whites will be on side. There is only so many racially motivated rapes and murders that even the most delusional of liberals can take.

There will, however, be holdouts. It’s a truly disturbing thought that there were even liberals in Rhodesia of all places whilst White women and children were being massacred, but this was indeed the case. There was, in fact, actually quite a few. World War 2 was only a few decades in the past, the barrage of anti-racist propaganda still fresh, the huge swing to the left which that conflict brought about still ongoing. For some, amazingly, this conditioning was enough to turn a blind eye to the White genocide in front of their very eyes. The very worst of this traitorous bunch, however, were the Todds, both father and former Rhodesian Prime Minister Garfield Todd, and his daughter, Judith Todd. Their story presents a stark warning to any who choose to side against their own in the racially explosive times in which we find ourselves.

Prime Minister Todd

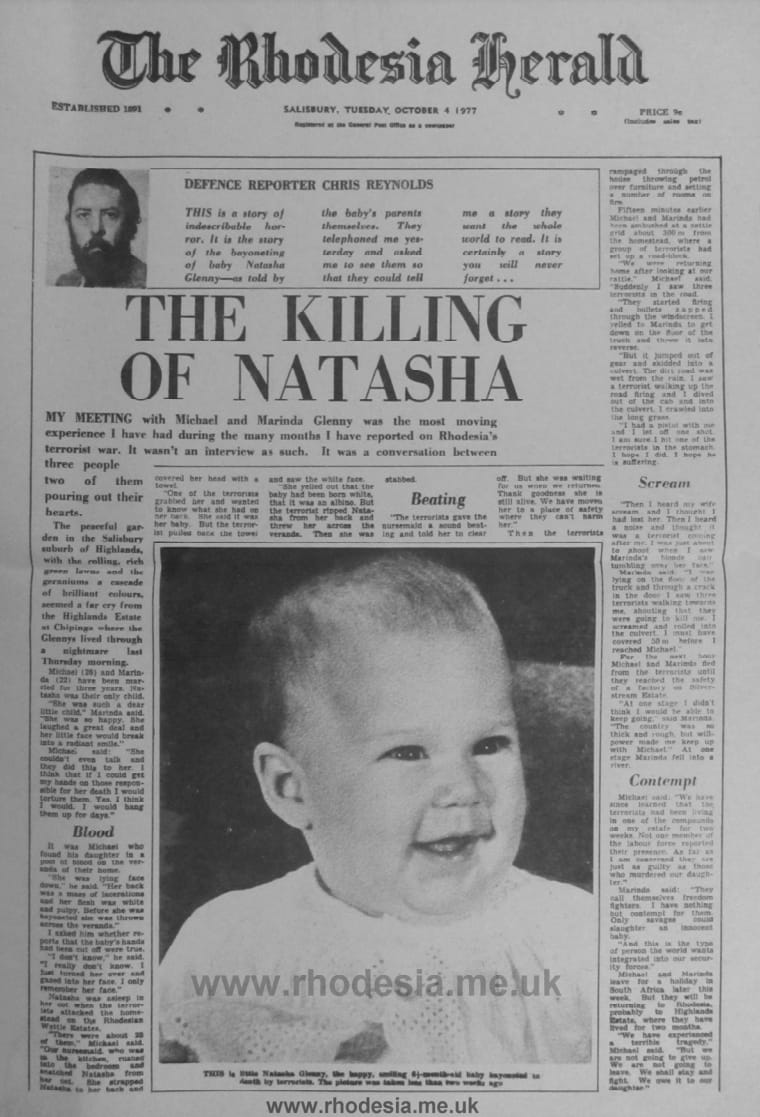

In 1953 the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was born, an attempt to carve out a functional Central African state right as decolonisation was ramping up. Upon the birth of the Federation Sir Godfrey Huggins became Federal Prime Minister, leaving his post of Prime Minister in Southern Rhodesia which he had held since 1933. In his place came Garfield Todd, a New Zealand born missionary who had ended up drifting into politics. He was a relatively unknown figure and in his own words a ‘political innocent’. From day one there was an air of uncertainty about this appointment but the Rhodesians were willing to give him a shot. It did not take long for Todd to let them down.

In Rhodesia the Land-Apportionment Act was sacred in the same way that the White Australia Policy was sacred to Australians. The Act essentially segregated Rhodesia along racial lines (no matter how nicely the Rhodesians would try and word it to distance themselves from apartheid in South Africa) and decided where the different races could purchase land. Imprudently, one of Todd’s first acts was to attempt to tamper with the Act in a way that would massively favour the Africans, damage the economy and flood White areas with Africans.

Todd had won himself no friends with this start. During a 1955 trip to the United States the Prime Minister admitted in an interview that at least 30% of the White population violently opposed his racial outlook for Rhodesia. This number would only have increased the following year when, despite Todd bending over backwards for the Africans, there was massive riots in the township of Harare, complete with Africans swarming through the streets smashing up shops and cars, burning down buildings and raping African women.

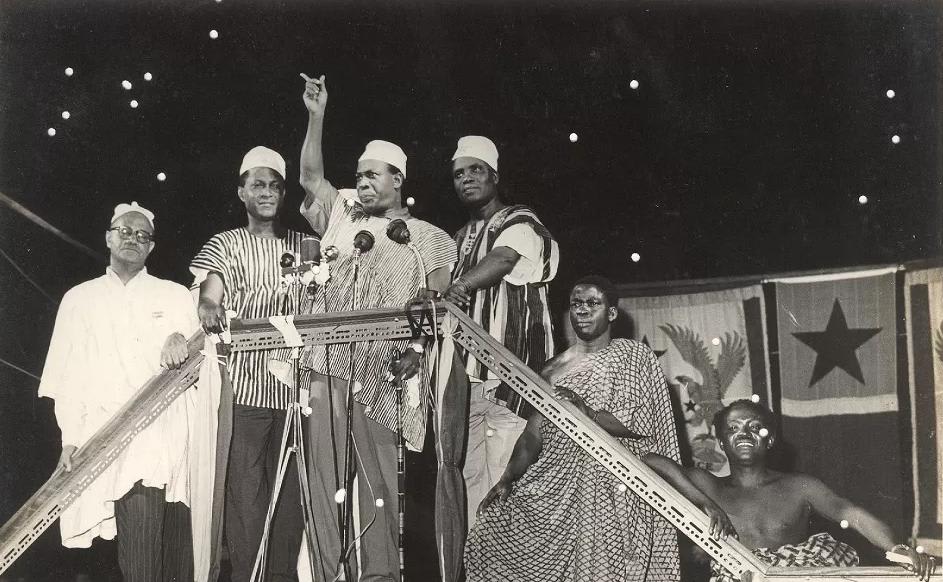

The next slap in the face for the Whites of Rhodesia came a year later. In 1957 Ghana achieved independence from the British Empire and, inexplicably, the Prime Minister jetted off with his Wife to attend the independence ceremony as the personal guests of the Ghanaian Prime Minister. As if celebrating the collapse of White rule in Africa wasn’t enough, the Prime Minister then returned home with a recording of the celebrations and began showing it to crowds of Africans as if to say ‘you, too, can have this!’.

1957 held another racial crisis for Todd. An African had returned home from his studies in the Netherlands but, the problem was, he was accompanied by his Dutch wife. Race-mixing was essentially unheard of in Rhodesia and this was actually quite a big deal, triggering a crisis. The biggest question of all was where this couple would live, the African or White areas of Rhodesia? Most Rhodesians were unanimous in wanting to strengthen the anti-miscegenation laws but Todd immediately came out saying that all such laws should be abolished. There was uproar and no action was taken either way.

The year brought a third crisis, a third strike for Todd’s standing with Rhodesians. The question of the franchise and African representation came up and Todd proposed measures which were so liberal that even the British Government and the American consul in Salisbury thought them a step too far. With a few modifications Todd got his way. During the Third Reading of the bill in Parliament MP Jack Keller gave his thoughts on the matter, the Rhodesian public would have much agreed:

‘This bill represents nothing more and nothing less than a base betrayal of the white people of this country… We are breeding, Sir, and nursing, thousands of lazy, good-for-nothing loafers in this country… This country is run by a negrophile Government… I oppose every word, every comma printed on the bill.’ 1

Todd may have got his way, but he was now all but finished. Todd had crossed the racial Rubicon and now stood on the far bank almost alone. In the wake of this latest crisis he scurried off to the Interracial Association of Southern Rhodesia and complained to them that Whites were becoming ‘a race of fear-ridden neurotics.’2

The worst problem of all with Todd’s antics was that he had given many of the Africans completely unrealistic hopes of progress. Over 3,000,000 of Rhodesia’s 4,000,000 Africans lived out in the Tribal Trust Lands, living very much as their ancestors had when the Rhodesians first arrived, just with modern amenities and without all the slavery and genocide. Taking these people from their current state to one-man one-vote democracy would be a process that would take centuries of White rule (if you even believed it was possible at all). Todd was trying to bring it about immediately, even to almost all liberals this would have be an impossible dream. Naturally, the Rhodesians rejected Todd’s attempted reforms and the Africans, perhaps also naturally, got the impression that progress was being barred to them even though in reality their lot was always steadily improving. If the Whites wouldn’t give them what Todd was offering via politics, they reasoned, then they would have to resort to violence.

The inevitable political revolt against Todd soon broke out. Todd, in response, tried to paint himself as some kind of great saviour that was holding back the black tide of violence. He and he alone was the African’s only hope of progress, he would remark in a speech. He then ran away from the crisis for a month-long holiday in the Cape. On the eve of his departure he secretly met with the leaders of the African National Congress who were currently engaged in a terror campaign against their own people. Ian Smith would write in bewilderment of this in his memoirs and it was, seemingly, the final straw.

When Todd returned home he was greeted by the news that the entire cabinet was about to resign. The next day’s cabinet meeting saw Todd come under attack from every angle. With his voice shaking he asked each member if they intended to withdraw their support. Every single one replied in the affirmative. Amazingly, Todd then accepted the resignations and attempted to just form a new cabinet.

On the 8th of February 1958 Todd was finally ousted for good at the United Rhodesia Party conference and Sir Edward Whitehead was elected in his place. Whitehead wasn’t anything special, but, as the Federal Minister of Education Benjamin Disraeli Goldberg remarked, “In the final analysis, if we have to choose between Todd and a donkey, then it’s the donkey!’’3

Rhodesia’s liberal experiment was over.

Pre-UDI

In the aftermath of his removal Todd kept at politics, consistently trying to play his preferred role of White saviour in which he and he alone could halt the ballooning African terrorist movement and instead run some form of happy multiracial liberal party that would bring about a multiracial Rhodesia in which the races could live happily ever after. Within a couple of years it quickly became clear that this just wasn’t going to happen and he began agitating against the Rhodesian government on long trips abroad instead, whether that be at liberal US Universities or in meetings with British politicians.

In 1960 a wave of African violence swept Rhodesia, the targets, especially when more serious violence was involved, tended to be other Africans. This violence was spearheaded by the National Democratic Party. Todd, incredibly, attempted to exploit this chaos by signing a letter along with key NDP figures such as Joshua Nkomo. The group ‘‘delivered a letter at the CRO [Commonwealth Relations Office] in London on 26 July 1960, calling on the British Government to suspend the Southern Rhodesian Constitution and to intervene with adequate armed forces to effect a peaceful transition to ‘democratic government based on the will of the people.’”4

Todd’s official biographer, Susan Woodhouse, writes of Garfield’s standing amongst Rhodesians by this point:

‘‘There was evidence of Garfield’s unpopularity among Europeans: driving home from Bannockburn, a carload of whites chased his car through the ranch. He did not dare stop and challenge them, as his young daughter Cynthia was with him. A threatening phone call from the Rhodesian Republic Army (later banned) was intercepted. And he never forgot the day he was quietly sitting in an airport lounge and ‘a fellow passing threw some silver coins at me: thirty pieces of silver.’ Ten years later would come assassination attempts, but for now he was more troubled by his decision to ‘quit politics’ than he was by his unpopularity.’’ 5

In March 1962 Todd addressed the United Nations about the situation in Rhodesia. In his speech he spoke of the need for the Rhodesian Government to meet with a representative of the people to create a new constitution. This was bizarre given that just a year earlier the Rhodesian Government, in collaboration with the British Government, had created the 1961 Constitution. Even Joshua Nkomo, the terrorist leader, had accepted the Constitution initially. The previous year’s Constitution, Todd said, was simply a ‘bad swindle’ 6 to keep power in White hands. If it was not repealed, he said, then bloodshed would follow in which the Whites would be routed. He would later regret this speech, calling it ‘horrible’.7 In that same year Todd once again spoke up, demanding that the British Government overrule the Whites of the Federation and force power into African hands using her legislative power.

That year saw even more violence in Southern Rhodesia, again, mostly resulting in dead Africans, burned African homes and burned African Churches at the hands of other Africans. Todd came out in the wake of this and said that the ‘Churches, trade unions, workers and professional people [of Rhodesia] should demand in writing that the Government respect the will of the people.’8, Todd, essentially, was asking the Rhodesian Government to capitulate to terrorism.

The final years before UDI, which saw Smith desperately try to make a deal with the British to avoid the inevitable, also saw Todd continue his work with the African Nationalists both within Rhodesia and around the world. Judith Todd, too, was following in her Father’s footsteps. The Daily News newspaper was banned in Rhodesia due to the publication being ‘contrary to the interests of public safety and security’9 and Judith arranged an illegal (seven days notice was required) protest outside Parliament. After being treated very leniently and repeatedly asked to disperse they continued to stubbornly refuse and were arrested.

In early October 1964 Judith was tried and found guilty, being made to pay a £25 fine, which Garfield covered along with her co-defendant’s. Meanwhile, as UDI approached, Todd continued to make regular visits to terrorists such as Joshua Nkomo who were in detention until he was forbidden to do so by law.

It was in these final months of 1965 that Todd accepted an invitation to participate in a Teach-In on Rhodesia at Edinburgh University. The Government had, by now, had quite enough of Todd galivanting about the world, besmirching the good name of Rhodesia and trying to whip up a storm against the Rhodesian Front Government. There was also the matter of all the working with terrorists, the trips to Zambia, and all the rest. Before heading to the airport the phone rang and Todd spoke but nobody answered. It was the police and they immediately got on their way as soon as it was confirmed Todd was in. Upon arrival Todd was informed that he was being restricted to his ranch for twelve months. Judith went to Edinburgh in her Father’s place instead and Ian Smith announced to the press that Todd had been locked up ‘because of his visits to Zambia to contact people who were aiding and abetting saboteurs.’10

Smith’s Rhodesia

On the 11th of November 1965 Rhodesia took the only chance at survival she had and declared her own independence. Todd, meanwhile, was rotting on his ranch and feeling very sorry for himself. His idleness, however, did not stop him assisting Rhodesia’s enemies. To a South African newsman he reported that he could see the trains going back and forth into Portuguese Mozambique from his ranch, breaching sanctions. The exact information regarding the number of petrol tankers and asbestos trucks was passed onto his friends for further distribution to the outside world.

As promised, in October 1966, Todd was let out of restriction. He rewarded Smith’s generosity by jetting off to New York and London before moving on to Australia and New Zealand. In the latter two countries especially the former Rhodesian Prime Minister was shocked by the amount of support for the Smith regime and he did all he could to persuade those he met to change their minds.

In 1968, again, Garfield ran cover for racially motivated terror. The Scottish Newspaper, the Daily Record, quotes him:

‘What Rhodesia needs is a solution more than a settlement. The whites there have to learn to understand the African and live with him. They won’t do it, you see. They depend on the Africans not to be people.’11

…

‘It wasn’t until the ‘fifties that the Africans started being really aware, and the whites to become terrified out of their minds… Nothing corrupts quite as much as privilege, and particularly privilege based on race… The Blacks will get their freedom eventually, of course. By blood if not by ballot box.’12

For the most part, though, in the late 1960s, Garfield had to be extremely careful. He remained politically active but the Rhodesian government was watching him like a hawk. His comments, generally, used religion as a kind of shield. Todd worked closely with the World Council of Churches, and, in September 1970, no doubt due to his influence, the organisation announced their first grants of $7,000 each to ZAPU and ZANU. The money, they said, was for ‘social welfare programmes such as childcare and help for mothers, and that is where the money will be used’. It goes without saying that two terrorist organisations which had already by now killed innumerous Whites and far more Africans was not going to be using that money on anything peaceful.

Garfield knew this full well and justified it, commenting to the Sunday Mail:

‘No Christian wishes to see force used but a growing number of members of world churches held that the violence being done to the spirit of the black man in South Africa and Rhodesia is intolerable and that it must be resisted… The aid is being given for social welfare programmes, not for armaments, and, in fact, if it were for arms, the total is so small it would hardly make a rifle’s difference.’13

The grants and Todd’s comments especially caused uproar from Rhodesia’s Whites, and, especially, her Churchgoing Whites.

The following year Todd once more ran cover for the terrorists in the British press, giving the Rhodesians two choices. They could either change their opinions or leave, as if Rhodesia did not belong to them. What would happen to those who did not change their opinions, of course, goes without saying. In a letter to The Times, ‘To avoid violence, Britain’s duty is to persuade the whites to change their opinions or leave the country… In a 1971 white Rhodesian context, no settlement, tragically, could be honourable.’14

The following year saw rioting as the Pearce Commission arrived to scout out the Rhodesian political landscape before the British accepted any proposals. The African Nationalists, with Todd heavily involved, kicked up a fuss deliberately to make sure the Commission rejected any proposals. Todd and his Africans demanded nothing less than complete white capitulation to African rule. This was quite enough for the Rhodesian authorities. Both Garfield and Judith were served with detention orders signed by the Minister of Law and Order. Garfield was taken to Gatooma Prison, Judith to Marandellas Prison and Todd’s houses and cars were searched.

Upon arrival at his new home Todd had to be segregated from the other prisoners given how low his reputation now was in the country. Judith, meanwhile, began an extremely over-dramatic hunger strike and had to be moved to Chikurubi High Security Prison. When Garfield heard about his daughter’s strike, he, too, began a hunger strike. His health rapidly deteriorated as a result.

Prime Minister Ian Smith was interviewed about his prisoners by the Guardian in early February 1972. ‘We are satisfied on the evidence before us at the moment that this is the most suitable way of dealing with the incredible state which existed in this country for a few weeks, when there was intimidation, violence, rioting, looting, burning and in fact some people even lost their lives.’ Smith was then asked if this meant that he linked the Todds to this state of affairs, to which the PM responded: ‘That is correct. I don’t say they are the only people responsible, but the action we took was because of the situation which existed.’15

Smith had both father and daughter released after six weeks, whereupon they were restricted to their ranch once again and banned from having contact with anyone outside the family without permission. Later in the year, though, thanks to the riots which Todd had helped whip up, the Pearce Commission determined that the latest Anglo-Rhodesian proposals were not acceptable to the African population. Intimidation and violence had won the day again.

In 1974 Rhodesia was in deep trouble. The Portuguese regime had been overthrown in a coup and her eastern flank was now wide open as the Europeans packed up and went home. Terrorists could now infiltrate the country far more easily via Mozambique’s huge land border. Worse, still, the South Africans forced Rhodesia to the negotiating table. A ceasefire was enforced and the Rhodesians were made to release their African detainees. Joshua Nkomo, whose terrorists had by now murdered untold numbers of Africans and Whites alike, asked for Garfield to be one of his advisors in his latest round of talks with Smith. The Rhodesian Prime Minister refused to release Todd, deeming him a top security risk.

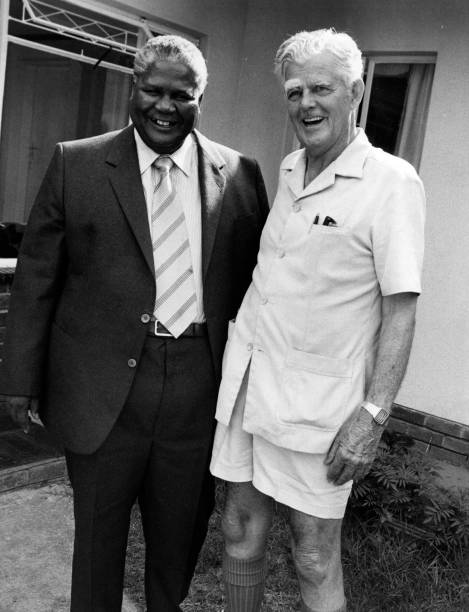

In early 1976 Garfield was given permission to go and visit his daughter in London and, in June, his restriction order was revoked. Ian Smith even accepted an interview which Garfield requested, but, ultimately, this was just a lecture in which Smith was told he was the only man who the Whites would follow and so he should just capitulate to African demands on their behalf.

The Rhodesia of 1976 was very different to the Rhodesia which Todd had initially been restricted from. No roads were really safe now and terrorists were everywhere. Garfield recalls that one day ‘coming from Bulawayo in the afternoon, I saw the guerrillas by the side of the road and they waved.’16 Todd was later asked about his support for the terrorists. Susan Woodhouse writes in her fawning biography of her former employer:

‘‘Garfield’s support for the guerrillas lay in food, cigarettes, toothpaste, aspirin, Coca Cola and, on one occasion, 180 pairs of boots. Garfield was once asked if he did not recognise that by not telling security forces of the presence of guerrillas, these men might then go on to kill white people. Yes, he admitted, there was guilt in that, but Garfield would never have helped anyone – guerrilla or soldier – to kill anyone. But, as Grace [Todd] said, ‘wherever your sympathies were… you were supporting people who were using violence.’’17

This was being very generous with the truth, it wasn’t as if Todd was restricted for no reason. As writer Graham Lord would recall in 2007 of his interaction with Todd ‘During the Civil War, Smith might well have had the liberal Todd hanged for treason, because Todd confessed to me secretly he had helped Mugabe’s guerrillas kill whites.’18

Todd himself would later admit in an interview with the Toronto Globe and Mail ‘Of course we were co-operating with the guerrillas. I’d have 20 of them sitting with their arms and their ammunition and their rocket-launchers on the front stoep in the middle of the night. Very dangerous.’19

Later he would say to Julie Frederikse:

‘Confined here as I was, under house arrest for four and a half years, I saw a lot of action. I was never actually involved in any violent act, but we felt there was no option but to support the Nationalist cause. And, you know, the violence came, first of all, from the Government. People don’t realise that violence generates violence, and that when you have your detention camps and your prison cells and your executions, naturally there is going to be a reaction on the part of the people. So that the Smith regime, they were the terrorists, in my estimation, who begat the guerilla war. Then of course when the people rose, naturally one’s sympathy was with them, although one hated violence.’20

…

‘There were a few occasions when the boys came to the house to see us, but usually they were very good; they kept away, largely because it was known that it was putting us into great danger should people actually come to me personally. So they came to our people, using people who were known intermediaries. They just gave the list of what they wanted, and it was drawn from the stores’21

1976 saw further talks between the the various terrorist groups and Smith’s Government in Geneva. This time Todd was allowed to come as an advisor to Nkomo, and, despite Todd repeatedly telling the British to directly intervene in Rhodesia militarily, the talks collapsed.

Todd grew bolder in 1977, jetting off for a trip around the United States where he pushed the terrorist cause and repeatedly slandered the Rhodesian regime in meetings and press conferences as well as TV and radio interviews. Then, back at home, Todd began to quietly meet with anti-Smith business and banking leaders, many of them Jewish liberals like Kipps Rosin.

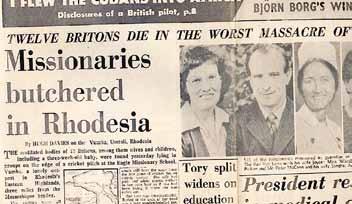

In 1977 Todd’s support for the terrorists reached it’s logical conclusion. His neighbour, Noel Webb, was brutally murdered by the terrorists which Todd had kept supporting on his ranch. Two days before this another farmer whose wedding Todd had officiated, Allan Ritson, was murdered on his farm nearby. In September there was a rocket attack on the white railway families’ village at Bannockburn, right beside the Todd ranch’s commercial centre. Many of Todd’s friends and neighbours, if they hadn’t already been murdered, began to flee, ‘taking the gap’ to South Africa across the Limpopo.

Todd, too, could’ve met his end in 1977. One of Rhodesia’s most prolific assassins, Ian ‘Taffy’ Brice was at the airport in Gaborone, Botswana, when he spotted Todd in the waiting lounge. After checking the tag on Todd’s bag to prove it really was him, Taffy then began keeping an eye on him. Both men were heading for Lusaka, the Zambian Capital, Todd, clearly, to go and meet with ZAPU officials. At the airport Todd was greeted by two well-dressed Africans and taken to the Continental Hotel which Taffy then also checked into, noting Todd’s room number on the register as he did so. For the next thirty hours Taffy sat in the hotel foyer bored out of his mind, waiting for Todd to leave. He recalled in See You In November:

‘I got so fed up with hanging around, that I seriously considered the idea of engaging in private enterprise and assassinating Todd anyway. It would have been contrary to instructions, for Salisbury’s authority was necessary to embark on such a course. Nevertheless, I was more than a little tempted.

I thought of using an old trick popular with the various government security services throughout the world. I would knock on his door. When he answered I would club him, sweep him bodily to the window and throw him out head first.

The inquest verdicts in such cases are invariably ‘accidental death’ or ‘suicide while of unsound mind’

Few Rhodesians would have mourned him.

At last my patience, or impatience as the case might have been, was rewarded and a car arrived to pick him up.

Ian and I followed the car straight to Joshua Nkomo’s home, a big house adjacent to President Kaunda’s official residence.

It was a house I’d get to know a lot more about later.’22

In 1978 Ian Smith was invited by 28 Republican senators to the United States and the Prime Minister did his best to make the most of a rare chance to push the Rhodesian cause to an influential audience. Todd was flown out at the exact same time and secured some interviews with men such as Cyrus Vance, the US Secretary of State. Here he did all he could to tarnish Smith and the regime, ideally ruining Smith’s visit.

On his way home Todd went via Brighton where he spoke to the Reform Group of Britain’s Conservative Party during their conference in Brighton. The Guardian reported that Todd ‘urged Conservatives yesterday not to support the internal settlement of Mr Smith and Bishop Muzorewa [An agreement had been reached for black majority rule between the African moderates and the Whites]. Mr Todd was heckled and jeered when he told the meeting that the guerrillas in Rhodesia were supported by the majority of the black population… Many of his audience were in an angry mood.’23

In 1979 the Todds moved to Bulawayo. The countryside was, by now, far too dangerous. They feared for their own lives from the very terrorists they were supporting, although this did not stop Garfield visiting a terrorist camp in June. At year’s end, Todd, despite not being a part of any official delegation, ran around the Lancaster House talks, interfering wherever possible to get his views across. Famously, an agreement was indeed signed at Lancaster House and the British arrived in Rhodesia to organise the transfer of power.

Here Todd once more found himself in hot water. He was approached by a ZANU-PF terrorist named Amin and asked for 300 dollars, which, like a good liberal, he readily provided. Shortly afterwards Garfield, supposedly to his utter surprise, found himself being arrested for ‘aiding a person in commission of acts of terrorism’24 He was remanded for three weeks and only after the intervention of Lord Soames, the new British Governor, was he released.

Later in an interview with the BBC Todd openly admitted that he was helping the terrorists.

‘Morris asked: ‘‘‘So, in actual fact, what you were doing was high treason?’’ ‘‘Oh, yes,’’ replied Garfield, ‘‘One knew that you had no defence… But there was no defence, because, everybody knew… so it was just nice that Lord Soames was in charge and I was freed within the twenty-four hours.’’’25

The election saw Mugabe intimidate his rival Africans out of the picture to such an extent that he swept to victory with ease. The British, too afraid to interfere despite that being their job, allowed this all to go on. Todd wrote on the 6th of March ‘Rejoice with us. On Tuesday, March 4th 1980, Zimbabwe emerged from persecution and war with a clarity of decision which has taken the world by surprise. This overwhelming expression of the people’s will is our recipe for peace. Our happiness is so great that it has almost banished the fear and anxiety under which we have lived for so many years; yet the joy and thankfulness which we share with almost the whole of the black people of Zimbabwe cannot eradicate the memories of what has happened.’26

Todd then went to meet Mugabe. Here he meekly asked firstly that he, as a former Prime Minister, be given easy access to the new Prime Minister, secondly he asked for an assurance that he wouldn’t be arrested. Mugabe put his hand on Todd’s arm and said that he wanted Todd in the Senate, adding ‘‘You have made a great contribution to the struggle and you deserve it. It is time those who in the past dishonoured you should now see you honoured.’’27 Todd accepted.

Mugabe’s Zimbabwe

Todd began life under Mugabe’s rule generously. He donated 3,000 acres of good arable land to a co-operative of unemployed and disabled ex-terrorists. In time it would house 480 of them. Judith, too, came with her husband to live in Zimbabwe once more with her Father. Garfield threw himself into his new Senatorial work, quickly running into trouble with his health given that he was 73 years old by late 1981. There was already trouble brewing, however, and despite all of the liberal delusions which Todd lived with, he, like everyone else, must surely have had some misgivings.

In February 1982 Nkomo and his ZAPU loyalists were dismissed from the Government, the economy was already in tatters with inflation soaring, unemployment was rife and the discovery of a cache of arms sufficient to equip 5,000 men caused political uproar. Soon enough the inevitable ethnic strife began, with Mugabe’s North Korean-trained 5th Brigade massacring thousands of innocent Matabele peasants.

Parliament opened in June 1982 and Todd spoke boldly, going over the terrible things happening in the country since independence at length. ‘Some criminally stupid things have taken place. On my own ranch, we have suffered five hold-ups by armed men… The law must be upheld but it should not be replaced by ministerial decisions… We are not at war – the Government is not threatened – the Prime Minister is firmly in the saddle… Let the light of public scrutiny, of the courts shine in on our problems so that we can see and understand.’28 In 1983, when nothing was done, Todd passed along all he knew about the atrocities against the Matabele to the US Ambassador.

Todd did what he did best and refused to keep his mouth shut. In May 1983 he made a speech about the Gukurahundi (the Matabele genocide) in Germany in which he held nothing back. This continued into 1984 during an interview with the Rand Daily Mail, ‘‘The biggest sadness to me has been the fact that ministers have considered themselves above the law – not that they would say that, but their actions, their statements, their threats, would make one believe they believe they have some magical power’’29

The country descended further into anarchy that year with violence breaking out in the Midlands and two African senators being murdered in their homes in 1984. There were incidents in Shabani, too, where Garfield was held up at gunpoint by a youth militia. This was not the only occasion at the time in which Garfield was held like this. Todd responded by once more speaking in front of the Senate about the situation, making ‘a plea not just to the government, but to everybody… we are faced on every side by a break-down of discipline. The percentage of our people who are involved with corruption, embezzlement, theft and a contempt for the rights of others, leading to assaults on homes, assaults on people, rapes, maiming, killing; the percentage is not very high but everything we are trying to achieve is threatened by these killings… one of the fundamental weaknesses in the security situation today I believe has to do with the trespass of party influence upon the work and duty of the police… the police must be freed from all political pressures.’30

Mugabe had by now, had quite enough. It was time for Todd to be taught a lesson, and the Prime Minister chose the harshest one he could think of. Judith Todd was suddenly arrested one morning, taken to a prison and led to a bedroom by General Agrippa Mutambara. He then handed her a bottle of beer and placed his gun, pointed at her head, onto the bedside table. She was then raped.

In 1985 Mugabe sought to consolidate his power further and introduce a one-party state. To do this he needed 70 seats in that year’s election. Despite a massive intimidation campaign ZANU-PF came up just short with 64 seats whilst ZAPU won 15. On the whites-only roll Ian Smith won 15 seats whilst the Independent Zimbabwe Group (which urged whites to accept the reality of black rule) gained five. Mugabe vowed revenge but, ultimately, ended up signing a unity accord with Nkomo in October 1987, merging ZAPU and ZANU-PF into a single party.

Todd, meanwhile, retired and was selected to be knighted by the Queen late that same year, the private investiture taking place at Buckingham Palace on the 5th of June 1986. A flood of phone-calls, cables and letters descended upon the Todds from around the world.

By 1990 Mugabe had, quite understandably, long since lost Todd’s support. Now, still, this old man in his 80s continued to speak out, criticising Mugabe for establishing a one-party state, for his corruption, his disregard for poverty and unemployment and for his undermining of the freedom of the press.

Todd was interviewed about his thoughts on Zimbabwe in 1994 by the Southland Times (New Zealand):

‘Today, fourteen years after the Union Jack was lowered over Harare [Salisbury] for the last time, Todd is less than enthusiastic about the self-proclaimed Marxist… “the radical rhetoric drove investors away and cost our young people untold thousands of jobs”… had the British heeded his advice in 1960, said Todd, independence could have dawned under a moderate black politician who could have handled the economy more skillfully. Instead, Mugabe tried to draw on failed economic policies from the Eastern Bloc and North Korea, plunging black Africa’s potentially richest nation into ruin. ‘‘Zimbabweans, having suffered so much under white rule, have been denied the rewards that are rightfully theirs’’, said Todd. ‘‘Zimbabweans are law-abiding and want Zimbabwe to succeed but Mugabe has shown lately that he holds the electorate in contempt.’’’31

Todd was, of course, the very man who perhaps did more than anyone else to sabotage the deal Ian Smith made with those ‘moderate black politicians’ which he was referring to.

Despite the hypocrisy, the criticism continued and in 1998, after his 90th birthday, Todd wrote in his Christmas letter to friends, ‘we live under a cloud of fear which has been generated by a regime of ‘‘absolute power.’’’32

In the year 2000 Robert Mugabe attempted to bring in a new constitution which allowed him to expropriate land without compensation. The people of Zimbabwe rejected this at the referendum and voted no.

Garfield wrote on the 7th of March that year ‘ Within Zimbabwe things are disastrous. ‘‘War veterans’’, many of doubtful credibility, are invading white farms in their hundreds, being bussed in by Government lorries and have taken over more than 100 farms so far. Dumiso tells them to get off the farms but earlier it was the President who said Government would not stop the invasions, so they are paying no attention.’33

Many of the farmers were Garfield’s friends and fellow travelers who had followed him over his long career. One such friend called in panic about her neighbours, ‘They have been given eight hours to pack and get off the farm! There is nothing he can do but get off! There seems no law, and the Police say that they cannot act as this is all a political matter and beyond their authority… Zimbabwe is on the brink of anarchy!’34

On the 15th of May he wrote again of the situation and, by now, it had grown even worse. ‘We are living with evil. This is not just incompetence or even greed but the intelligence and determination of the Government are a manifestation of evil and it is frightening… This morning 60,000 British passport-holders have been told that their Zimbabwean passports are cancelled so they are just British, therefore foreigners, and therefore will have no vote in the coming election. I doubt there are 60,000 of these people who hold two passports but of course we know friends who are now disenfranchised.’35

The Todds themselves were then threatened with an invasion by ‘war veterans’ who would expropriate their land. This did not come to pass, but Todd’s troubles were not at an end.

In June the nation headed to the polls and, like usual, there was massive unrest. Fourty opposition supporters and three white farmers were murdered. Todd attended a MDC (Movement for Democratic Change) rally and publicly endorsed them from the stage. He urged those in attendance to think of the victims of Mugabe’s terror and to vote the right way. The audience, which was 90% black, was left hanging on his every word, fascinated by the life story of this 91-year-old who was giving quite the performance.

Despite massive election fraud and intimidation Mugabe’s ZANU-PF only just clinched a victory over the MDC.

Things quickly went downhill for Todd. Grace, his wife, finally passed away on the 30th of December 2001 after years of struggle, especially in recent years with all of the stress put upon the family. Early the following year, on the 12th of February, Garfield made a statement to the press in which he announced that his citizenship had been revoked despite him having been in the country for 67 years. Mugabe had finally taken his revenge. On the 13th of October 2002, Garfield, too, passed away at the age of 94.

The following year Judith, too, despite being born in Rhodesia, was stripped of her citizenship and became stateless. Only thanks to the generosity of the New Zealand Government was she able to acquire a passport.

This was the reward for Garfield, Grace and Judith Todd for three lifetimes of dedicated service to the cause of liberalism and anti-racism. The reward for betraying their own race. Their cases are not unique, far from it, but will lessons be learned? Given that Judith is still alive and still engaged in liberal and anti-racist activism to this day the answer isn’t so certain.

In this world, in which we are being outnumbered further and further by the day, we will all eventually be forced to pick a side. Things will not always be crystal clear. You will not always be able to put everything into neat little categories of good or bad, right or wrong. It is easy to get lost in the nuance or distracted by sideshows. You will, still, have to pick a side. Your own side or the side of those who want you dead. Make sure you make the right choice.

Thank you very much for reading. If you made it this far then please do consider becoming a Paid Subscriber for access to my Paid only videos.

Garfield Todd: The End of the Liberal Dream in Rhodesia, Susan Woodhouse, p199

Rhodesia: A Complete History 1890-1980, Peter Baxter, p387

Bitter Harvest: The Great Betrayal, Ian Smith, p35

So far and no further!, JRT Wood, p46

Garfield Todd: The End of the Liberal Dream in Rhodesia, Susan Woodhouse, p317

So far and no further!, JRT Wood, p102

Ibid

So far and no further!, JRT Wood, p113

Garfield Todd: The End of the Liberal Dream in Rhodesia, Susan Woodhouse, p344

Quoted in Sunday Mail, 24.10.65

Quoted in Daily Record, 20.11.68

Ibid

Quoted in Sunday Mail, 10.09.70

Quoted in The Times, 10.11.71

Quoted in The Guardian, 11.02.72

Interview with Susan Woodhouse, 1997

Garfield Todd: The End of the Liberal Dream in Rhodesia, Susan Woodhouse, p408-409

Quoted in Mail on Sunday, 25.11.07

Quoted in Globe & Mail, 19.02.88

None but Ourselves: Masses vs Media in the Making of Zimbabwe, Julie Frederikse, p230-32

Ibid

See You In November, Peter Stiff, p187

The Guardian, 13.10.78

Garfield Todd: The End of the Liberal Dream in Rhodesia, Susan Woodhouse, p443

Garfield Todd: The End of the Liberal Dream in Rhodesia, Susan Woodhouse, p444

Garfield Todd: The End of the Liberal Dream in Rhodesia, Susan Woodhouse, p450

Garfield Todd: The End of the Liberal Dream in Rhodesia, Susan Woodhouse, p451

Garfield Todd: The End of the Liberal Dream in Rhodesia, Susan Woodhouse, p461

Quoted in Rand Daily Mail, 17.09.84

Todd in the senate, 12.12.84

Interview in the Southland Times, 23.02.94

Garfield Todd: The End of the Liberal Dream in Rhodesia, Susan Woodhouse, p503

Garfield Todd: The End of the Liberal Dream in Rhodesia, Susan Woodhouse, p506

Ibid

Garfield Todd: The End of the Liberal Dream in Rhodesia, Susan Woodhouse, p507

Zoomer HistorianRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1