Isaac Newton’s Lost Papers – And His Search For God’s Divine Plan

Authored by Duncan Burch via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Few have had as profound an effect on modern scientific understanding as Sir Isaac Newton.

Many people are familiar with the story of how a falling apple first inspired Newton to investigate the force that would come to be known as gravity, and as he later concluded in his seminal scientific treatise, “Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy,” it is this same force that pulls a fruit to ground that keeps the planets in orbit.

While Newton undoubtedly possessed a keen sense of observation and an insatiable curiosity that enabled him to make some of the most influential mathematical and scientific discoveries in recorded history, his prolific notes and writings—especially the vast amount of manuscripts that went unpublished until hundreds of years after his death—reveal a more profound motivation.

Newton wrote more, arguably significantly more, on theology than on scientific phenomena. According to those most familiar with the totality of his writings, he viewed the two not as distinctive pursuits, but as one unified quest to map out the divine order of the universe.

Although Newton is justifiably renowned for his numerous astounding scientific contributions, what is less known about him is that he was also a devout Christian, a dedicated scriptural scholar, and one of the most preeminent theologians of his time. While his public scientific works blossomed in full view of the world, it was his private religious studies that served as the unseen roots providing sustenance to those blooms.

A Devout Christian

Because of his demonstrated mathematical prowess, in 1669, at the age of 26, Newton was appointed as the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge. At the time, all Cambridge professors were required to take the holy orders of the Church of England, but Newton at first delayed and ultimately refused to take the oath.

However, this refusal did not stem from his lack of faith or a rejection of the Bible, but in fact just the opposite—he believed that the church had embraced certain misinterpretations of the Bible that he could not in good conscience profess to believe. Newton was fluent in both Latin and Greek, and it was his extensive studies of original scriptures that led him to reject certain tenets of the church, specifically those concerning the Trinity.

Though he did not speak or write publicly about his disagreement with church doctrine, fearing that controversial theological arguments could inhibit or undermine his scientific research, his refusal to take the holy orders posed a serious threat to his early career.

Fortunately, some of his fellow teachers petitioned the king on his behalf, and he was ultimately granted a special dispensation that exempted him from the oath requirement and allowed him to remain in his position at Cambridge. It was around this time that Newton began to record his theological research in notebooks. And this was no passing fancy for the great scientist, as throughout the remainder of his life, he continued to write and revise his extensive theological notes and Biblical interpretations.

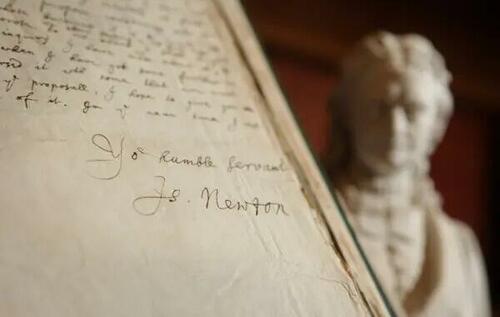

Many of his contemporaries were aware of his private work and considered him an authority on Biblical theology. Newton corresponded extensively on matters of Biblical interpretation with luminary thinkers and scholars, including the philosopher John Locke and the influential theologian John Mill. At one point, even the Archbishop of Canterbury, the senior bishop of the Church of England, stated that Newton knew more about the Bible than any members of the clergy.

A Divine Order

Despite the fact that Newton never published the vast majority of his theological writings, what he did publish during his life left little doubt as to his belief in the intelligent design of the universe by a divine creator. Although Newton almost completely avoided the topic of theology in his most famous scientific work, the “Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy,” when he published the second edition of the work in 1713, he included an addendum known as the “General Scholium,” around half of which is devoted to his theological conception of the universe.

“The Supreme God is a Being eternal, infinite, absolutely perfect,” he wrote. “And from his true dominion it follows that the true God is a living, intelligent, and powerful Being. … He is not eternity and infinity, but eternal and infinite; he is not duration or space, but he endures and is present … by existing always and every where, he constitutes duration and space.”

So even during his lifetime, Newton’s belief in a divine order and a supreme creator was well known. What was not well known, though, was the vast extent of his scriptural scholarship and writing. His unpublished papers consisted of more than 6 million words, approximately one-third of which were devoted to scriptural study and theology.

After Newton’s death in 1727, thousands of pages of notes and unpublished writings were acquired by his closest living relatives, but out of concern that the papers would offend the church and damage his scientific reputation, the relatives kept them private. As a result, the majority of his papers remained hidden from public view for nearly 150 years.

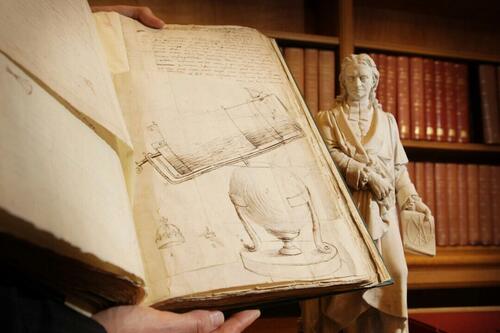

In 1872, most of Newton’s scientific and mathematical papers were donated to the University of Cambridge, where they were catalogued and made available to scholars. But the remainder of the papers, including those concerned with theology and biblical scholarship, remained private until they were put up for auction by Sotheby’s in 1936.

The auction was not widely publicized and was generally overshadowed by other auctions occurring around the same time, and as a result, the papers were scattered to various collectors and dealers around the world. However, shortly after the auction, two men set out to acquire different portions of Newton’s lost papers.

Saving the Lost Papers

One of these men was the prominent economist and mathematician John Maynard Keynes, who focused primarily on acquiring Newton’s notes on the subject of alchemy, of which there were many. The term alchemy connotes different things to different people, and while it is sometimes associated with occult magic, it is also considered to be influential in the development of modern chemistry. Even among Keynes and others who have studies Newton’s lost writings on alchemy, there seems to be no clear consensus on what he was studying or why.

The other man who aggressively set out to acquire Newton’s lost papers was the Jewish scholar and linguist Abraham Yahuda, who focused primarily on the acquisition of Newton’s theological writings.

Yahuda was a rabbinical philologist who taught and lectured at numerous prominent universities in Europe and around the world throughout the early decades of the 1900s, and he was also a collector of rare manuscripts. Although he was an accomplished linguist who studied the early writings of many cultures, his primary field of study was the philology of the Torah, and he recognized Newton as someone who was also deeply interested in accurately interpreting the symbolic language of the Old Testament.

By the late 1930s, Yahuda had acquired thousands of pages of Newton’s manuscripts, with which he fled to London at the outbreak of World War II.

In early 1940, his acquaintance and fellow scholar Albert Einstein helped arrange for Yahuda and his wife to travel to New York, and later that summer the two men met at Einstein’s summer retreat in the Adirondacks. Apparently, they discussed Newton’s lost papers that Yahuda acquired because Einstein wrote to him later that year concerning the topic.

“Newton’s writings on biblical subjects seem to me especially interesting,” Einstein wrote, “because they provide deep insight into the characteristic intellectual features and working methods of this important man. The divine origin of the Bible is for Newton absolutely certain, a conviction that stands in curious contrast to the critical skepticism that characterizes his attitude toward the churches.”

In his letter, Einstein also lamented the fact that most of the preparatory works of Newton’s physics writings had been lost or destroyed, but he was convinced that the theological works could provide valuable insight into Newton’s thinking and methods. At least, he concluded, “we do have this domain of his works on the Bible drafts and their repeated modification; these mostly unpublished writings therefore allow a highly interesting insight into the mental workshop of this unique thinker.”

Although Yahuda never published or sold his collection of Newton’s papers, he did write about them, and he was one of the first scholars to understand and note the importance of Newton’s theology on his broader work. After his death in 1952, his wife donated the papers to the Jewish National and University Library at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where for the first time they were made available to the public.

In the ensuing decades, many scholars and writers began to study and publish papers on Newton’s theological writings, ultimately providing an expanded perspective into the thinking of one of the world’s most influential scientists. At the turn of the century and in the years since, several organizations, including The Newton Project, have set out to catalogue and publish the lost theological writings of Isaac Newton, many of which are now available to the general public and easily accessible online.

Newton’s Search for God’s Divine Plan

“Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy,” published in Latin in 1687, in which Newton formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation, is perhaps the most influential scientific treatise ever composed, not only for its insights into classical mechanics and the functioning of the physical world but also for its advancements of scientific methods of inquiry.

Newton made significant contributions to many fields of scientific study, including mathematics, optics, and physics. His studies of prisms and the light spectrum led him to design and build the first reflecting telescope, and he also made the first attempts to calculate the speed of sound. As a mathematician, he was the first person to employ the principles of modern calculus, and he was a pioneer in numerous areas of mathematical theories and calculations.

While his influence on the history of science is well known and undeniable, his prominence as a theologian has only come to full light more recently with the publication of his lost papers.

There is no doubt that Newton was a man of devout faith, and that faith inspired and informed his scientific inquiry. As he wrote in the General Scholium, “This most beautiful system of the sun, planets, and comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful being.”

As scholars continue to study his lost papers, perhaps more insights into Newton’s conception of the universe will be revealed.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 01/29/2026 – 22:35ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1