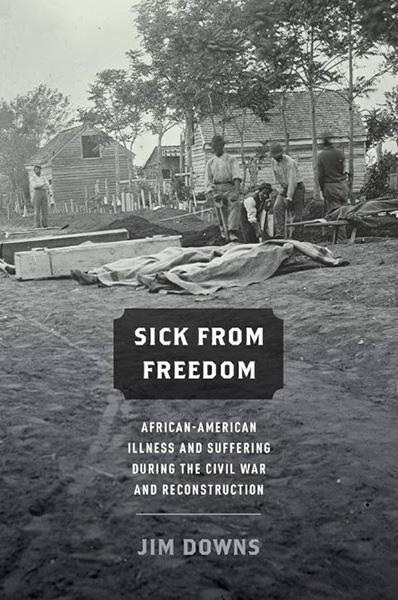

Jim Downs, Sick From Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction, Oxford University Press, 2012, 264 pp., $30.54 (softcover)

This book is about something I had never really thought about: What was emancipation like for the slaves? Jim Downs, Professor of Civil War Studies and History at Gettysburg College, explains that contemporary historians did not gloss over the countless thousands who died of starvation and disease. In the 1970s, however, the story changed, as historians went “in search of heroic icons to shatter racist stereotypes.” They imagined freed slaves “as powerful and independent actors,” “whose embrace of freedom miraculously came with little cost.” As a result, “references to freed slaves as sick and dying literally vanished from the historiography.” Today, it is common to claim that the shift to freedom came easily — even that blacks freed themselves — but this ignores tremendous suffering.

Prof. Downs wrote this book to correct the record, with a special emphasis on deaths from disease. He declines to estimate how many slaves died because of emancipation — no one was keeping records — noting only that freedom was wrenching and often fatal.

Prof. Downs notes several reasons for this. First, emancipation came suddenly and without planning. Many people in the North assumed the war would eventually end slavery, but no one had thought about what would happen next. Union men who recalled the smooth emancipation in the North seem to have forgotten that it was very gradual. In most states, anyone a slave remained a slave until death, and children born to slaves were indentured until at least age 21. At the outbreak of the war, there was still a handful of black slaves in New Jersey. Emancipation was gradual in British colonies and in Cuba and Guadeloupe, as well.

Second, in America, freedom came as part of a terrible war that devastated cropland, destroyed infrastructure, and uprooted millions of people, white and black. Both North and South expected a quick war. No one was prepared for “massive dislocation, widespread poverty, prolonged starvation, and, most of all, the dramatic outbreak of sickness and disease.” This was the worst time to abolish an institution that influenced nearly every aspect of social and economic life.

Third, medicine was primitive, especially wartime medicine. At the Battle of First Manassas in July 1861, neither side was prepared to treat hundreds of badly wounded soldiers or even bury the dead. Most doctors had come from small private practices or worked in charity hospitals. No one was prepared for mass casualties.

Nor was anyone prepared for the raging epidemics that followed movements of troops and black refugees. Germ theory was not understood, nor was basic sanitation. No one even knew that mosquitos carry malaria. Prof. Downs writes: “Army traffic and military activities commonly created mosquito breeding sites by disrupting drainage systems. They also caused the accumulation of animal offal, garbage, and human excreta, and attracted diseased camp followers.” Soldiers ate bad food and slept in tents — or in the open — even in winter.

Everywhere, there were outbreaks of “dysentery, camp measles, epidemic mumps, inflammatory diseases of the respiratory organs, malaria, and pneumonia,” with dysentery the worst killer. Men packed together could hardly avoid infection, and armies on the march spread sickness wherever they went. Of the 700,000 men in uniform who were lost, two-thirds died of disease. Many commanders had so many sick men, they could hardly fight the enemy — and these were fit young men whom governments fed, clothed, and tried to keep healthy.

It was into Union camps like these that escaped slaves began to arrive.

Contrabands

Of the four million slaves at the outbreak of the war, some 500,000 fled to freedom as battle lines moved South. Many escaped slaves traveled for days or even weeks to get to Union units and often arrived sick and starving, with only the clothes on their backs. In the early days of the war, commanders followed the Fugitive Slave Act, and sent slaves back to owners. General Benjamin Butler may have been the first to see them as potential labor to be taken from the South and put to work for the Army. He called ex-slaves “contrabands,” short for “contrabands of war,” or seized enemy property. He has been credited with pioneering the idea of freeing escaped slaves, but he saw them only as labor; he once reported that in just three days, $60,000 worth of blacks had streamed into his camp.

Officers fighting a war hated dealing with crowds of black men, women, and children. Soldiers called them “refugees” or even “vagrants,” until “contrabands” caught on. What were called the Confiscation Acts set rules for using black labor to help defeat the Confederacy. The Second Confiscation Act of July 17, 1862, added that after the war, freed slaves were to be colonized or sent away to “some tropical country beyond the limits of the United States.” There was no concept of trying to fit them into American society. Lincoln worked constantly to find a place to which freed blacks could be sent. For him, their interests were far subordinate to his main goals: preserving the Union and ending the mutual slaughter of white people.

Union commanders started hiring able-bodied men as laborers, generally with the agreement that the Army would issue tents and rations to family members. Unattached women and children or old men usually got nothing. They clustered around campsites in miserable conditions, begging for food and shelter, and many died. Often, Union soldiers who had never seen blacks hardly considered them human. Their bodies were often dumped into pits, along with dead pack animals. Some officers got tired of feeding family members and drove them off, along with other unemployable contrabands. Many died.

The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, freed slaves in Confederate-controlled territory, but did not grant them citizenship or any means of support. The Union Army needed only so many contraband laborers, but as it moved South, commanders found abandoned plantations that could be cultivated. Surplus blacks now had a use: “Freed people were coerced to return to the plantation South as laborers.” Contraband camps became the equivalent of slave pens, where newly landed Africans had been held before they were sold.

Officers set up what were called Departments of Negro Affairs, which sent blacks to work on plantations. This was profitable. During 1866 and 1867, the Army grew more than two million bales of cotton, and the Treasury Department collected more than $40 million in taxes. Working conditions were little different from slavery, but these men had shelter and food — and lived. Many escaped slaves drifted into towns and cities behind Union lines, living on the streets or in any shelter they could find.

Elizabeth Keckley was born a slave, but she bought her freedom and worked as a dressmaker for Mary Todd Lincoln. She visited hovels in Washington DC, where escaped slaves lay on bare floors, dying of disease and starvation. She wrote of her sorrow at the sight of “poor dusky children of slavery, men and women of my own race — the transition from slavery to freedom was too sudden for you!”

Elizabeth Keckley

John Eaton was a Union chaplain who spent the war trying to help blacks. He wrote that it was clear that the immediate question was not, “How was the slave to be transformed into a freedman?” Instead, it was, “How was he to be fed and clad and sheltered?” Eaton stopped celebrating “the joys of freedom,” and started mourning the “sorrow and desolation of the civil war period.”

John Eaton

The Freedmen’s Bureau

The terrible lack of medical care for blacks got worse as the war went on. One military official who arrived in the South after the war said that freed people “were crowded together, sickly, disheartened, dying on the streets . . . no physicians no medicines no hospitals.” He said, such scenes “were calculated to make one doubt the policy of emancipation.”

There was no question of reinstituting slavery, but plantations had been communities in which young slaves were reared to productive work, and older slaves tended the young and helped out as they could. After the war, both blacks and whites struggled to find work in a devastated economy, where each man was worth no more than what he could accomplish each day rather than be seen — as a slave was — as a life-long asset. Day-wages could hardly cover the needs of whole families.

Likewise, when blacks were property, owners hired doctors to treat them. No more. As one former master explained, “When I owned niggers, I used to pay medical bills and take care of them; I do not think I shall trouble myself much now.”

As war finally drew to an end, many in the North argued that because abolitionists had insisted on emancipation, they should go South and save the suffering blacks. Indeed, former abolition societies renamed themselves freedmen societies, and volunteers — mostly ladies — marched South with Bibles and books to uplift former slaves. They found shocking numbers of sick and dying, who needed food and medicine rather than Bibles.

Clearly, there could never have been enough private charity, so the US government took responsibility. On March 3, 1865, just five weeks before Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Lincoln signed a bill to establish the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, commonly called the Freedmen’s Bureau. It was part of the War Department.

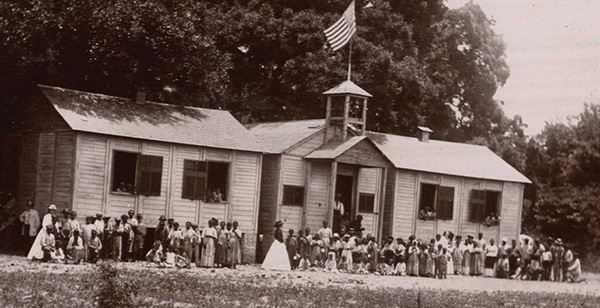

The bureau had four divisions, one to try to find land for blacks, one to educate them for employment, a legal division to mediate disputes between former slaves and masters, and a medical division.

That division, with which this book is primarily concerned, operated like antebellum charity hospitals. In the 19th century, only poor people went to hospitals. Everyone else hired doctors to treat them at home. It was as much an indignity to go to a hospital as it was to live in an almshouse or an orphanage, and these functions were often combined in the same location.

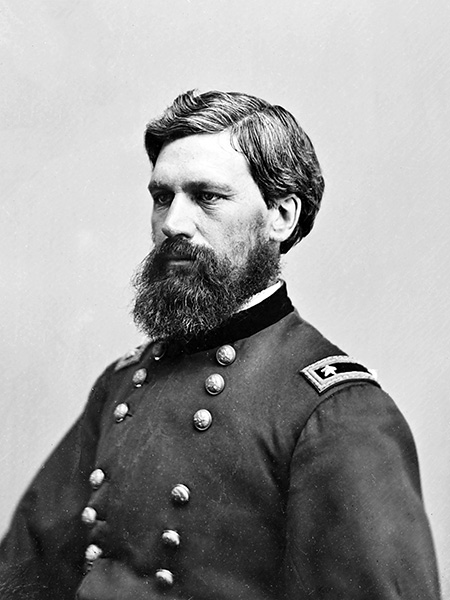

There was much fear in both North and South that Bureau hospitals — all told, about 40 were set up throughout the South — would end up supporting layabouts. The man appointed to run the Bureau was Army General Oliver Otis Howard, a pious humanitarian known as “the Christian general.” However, in his very first directive, he wrote: “The negro should understand that he is really free but on no account, if able to work, should he harbor the thought that the Government will support him in idleness.” Handouts to healthy people would encourage “systemized pauperism.” Howard was also determined to build schools for blacks; they would learn a trade and avoid “beggary and dependence.” Volunteers from the North ran classes in good manners, sewing, and cleaning, so that black women could go into domestic service and support themselves.

Oliver Otis Howard

Bureau hospitals nevertheless became feeding shelters for indigent blacks. During crises, such as the famine of 1866–1867, some hospitals even delivered weekly rations to starving blacks in the countryside. Orphans could not be turned away. Many drifted into Bureau hospitals, some of which housed and fed them in separate annexes.

The legality of this civilian — and exclusively black — welfare program was never tested, but opponents said it exceeded Constitutional authority. When the Bureau’s enabling act came up for renewal in 1866, President Andrew Johnson vetoed it as government overreach, as a violation of states’ rights, and as discrimination against poor whites whom it did not serve. Congress overrode his veto.

During nearly four years, the medical division treated some one million people. Many lives were saved, but many were lost. Chaplain John Eaton complained about hospital staff, who were often Union soldiers: “the soldiers in the Army were a good deal opposed to serving the Negro in any matter.” Some doctors refused to put an ear to the chest of a black, which was a common way to listen to lungs and heart.

Bureau doctors often had no experience with black patients, and some had exaggerated notions of racial differences. The sickle-cell trait can give blacks some protection against malaria, but many Northern doctors thought blacks were completely immune. Southern doctors had routinely treated blacks with quinine, but Bureau doctors caused unnecessary deaths by withholding it.

Some Northern doctors likewise thought smallpox was incurable in blacks, even though antebellum doctors vaccinated slaves and enforced quarantines in “sick houses.” During the epidemic of 1865–1867, roughly 30,000 blacks in the Carolinas died of smallpox in just six months. Prof. Downs writes that Bureau doctors certainly did not want blacks to die; many just thought there was no way to help them, so they didn’t try. Some officials in Washington thought high death rates heralded the coming extinction of blacks, which some anti-abolitionists had predicted if slaves had to fend for themselves.

Bureau hospitals had unexpected expenses. When a slave died, his master buried him on the plantation or arranged for a plot in a colored cemetery. The bureau initially had no budget even for coffins, much less cemetery space, and all applications for funds had to go through a complex bureaucracy. Many bodies quietly disappeared into Southern medical schools for dissection or experimentation.

The Bureau constantly tried to get Southern hospitals and almshouses to take in blacks, but they were full of poor whites. Southerners also claimed that freedmen were not citizens, with no claim on state or county services.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 granted blacks the rights of citizens, which included the right to services, but many Southerners still refused to accept them. A particular problem were “insane colored paupers.” Sometimes Bureau hospitals set up wards for mental patients, but this was seldom practical. Many Southern counties did not have lunatic asylums either, and there was only a single, central state mental hospital. Bureau doctors started issuing “certificates of insanity,” by which unmanageable blacks could be transferred to the state.

The Medical Division turned over all its facilities to the states by late 1869 — with one exception. What was known as Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, DC survived and eventually became Howard University Hospital. (The university itself takes its name from its founder, General Howard, head of the Freedmen’s Bureau.) The Bureau was officially dissolved in 1872, and Reconstruction ended in 1877.

Freedmen’s Bureau school in South Carolina.

The spirit of the Bureau moves west

Professor Downs notes, however, that the spirit of the bureau lived on — in the American West. The Army proceeded to do with the Indians what it had done with blacks: change their way of life (from hunters to farmers), move them in large numbers (onto reservations), set up schools for them, and start feeding and medical programs. Many of the staff of the Freedmen’s Bureau — including its boss — transferred to the Office of Indian affairs. In 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Howard to “deal with Indian affairs in the West,” where “the Christian general” continued to burnish his humanitarian reputation. Needless to say, he is now generally considered a racist and imperialist.

Today, of course, we are used to welfare, but in Lincoln’s time, the federal government had never met the bodily needs of civilians. It did not even operate prisons. Ironically, the very first beneficiaries of federal food and medical programs were the people the United States is said to have mistreated most viciously: blacks and Indians.

The post And They Died by the Tens of Thousands appeared first on American Renaissance.

American RenaissanceRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1