Why Skyrocketing Premiums Were Inevitable With Obamacare’s Design

Authored by Lawrence Wilson via The Epoch Times,

The Affordable Care Act would “bend the cost curve” in health care, “moving the health care system toward higher quality and more efficient care.” So said a White House statement in 2013.

Many people now agree that didn’t happen.

“We pay more than any other country in the world for worse health care,” Sen. Elissa Slotkin (D-Mich.) said while campaigning for office in 2024.

“Families pay more, get less, and we’re left with few choices,” Rep. Mike Lawler (R-N.Y.) testified in a December 2025 committee hearing.

A combined 70 percent of Americans believe the U.S. health care system is either in crisis or has major problems, according to a 2025 Gallup poll.

Health insurance premiums have more than doubled since Obamacare began in 2014, rising twice as fast as inflation. And satisfaction with the cost of health care registered a record low in 2025, at 16 percent.

How did that happen?

Many consumers believe insurance companies are responsible. Insurers shift the blame to hospitals and pharmaceutical companies. Pharmaceutical companies say pharmacy benefit managers are at fault. Political parties blame each other.

Some independent observers agree that the rise in premiums, especially recently, is largely driven by external forces, including the increased use of expensive medications, rising labor costs, and inflation, which reached a 40-year high in 2022.

Others see a more basic cause, one with roots in the Affordable Care Act, the federal law that created Obamacare. Some of the same policies that make Obamacare popular with consumers are actually cracks in its foundation, these observers say. Those policies all but guaranteed premium increases, especially in the program’s early years.

House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) speaks to reporters as he leaves the House chamber at the U.S. Capitol on Dec. 17, 2025. On Jan. 8, 2026, seventeen House Republicans joined Democrats to pass a three-year extension of the expired Affordable Care Act premium tax credits. Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

Here are the key provisions of Obamacare, which some experts say undermined its success.

Foundations of Obamacare

The Affordable Care Act made profound changes in the health insurance industry. One of the changes required insurance companies to issue health insurance in the individual and small-group markets to any applicant, regardless of pre-existing illness.

Americans generally like that idea. More than two-thirds of the public says that provision is very important, according to polling by health care research group KFF. That includes 54 percent of Republicans, 66 percent of independents, and 79 percent of Democrats.

Known as guaranteed issue, this was one of four foundational provisions built into Obamacare to make health insurance available to more Americans.

The second foundation was community rating, which required insurers to rate, or price, their plans based on the demographic profile of a community, with only limited increases based on age and tobacco use. According to this provision, premiums for people of the same age group in the same geographic area are pretty much the same.

The third foundation was the requirement that certain essential health benefits be included in every plan, except for catastrophic health plans. This ensured that consumers would get real value for their money and not be surprised to find that services such as emergency room visits or maternity care were not covered.

The Department of Health and Human Services eventually decided on 10 essential health benefits.

The final foundation was the individual mandate. This required most adults to either buy health insurance or pay a fine. The point was to keep overall costs down by ensuring that young, healthy people, who would likely incur fewer charges, would stay in the market. The fine was $95 per adult in 2014 and rose to $695 by 2016.

Informational pamphlets are displayed during a health care enrollment fair in Richmond, Calif., on March 31, 2014. Health insurance premiums have more than doubled since Obamacare began in 2014, rising twice as fast as inflation. Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Though some of these provisions were popular with consumers, they increased both cost and risk for health insurers. And though the new rules made insurance premiums lower for some customers, prices went up for some others.

And the new rules applied to all new plans for individual and small-group insurance sold in the United States, guaranteeing a shift in the entire market, not just the Obamacare exchanges.

Higher Cost, Increased Risk

As the Affordable Care Act was being considered and implemented, stakeholders warned that these sweeping changes could make insurance more expensive. At a minimum, they said, the requirement that plans cover a suite of essential health benefits could raise premiums.

The Board of Health Care Services at the National Academies warned that including too many essential health benefits could make insurance unaffordable for individuals and small businesses.

“If this occurs, the principal reason for the [Affordable Care Act]—enabling people to purchase health insurance and thus covering more of the population—will not be met,” the board wrote in 2012.

Insurers were wary too. America’s Health Insurance Plans, an industry trade group, told regulators in a 2012 letter that the choice of essential health benefits would have “far-reaching implications” on the affordability of health insurance.

Increased risk was also a concern.

Insurers speculated on the legality of the individual mandate and warned that Obamacare wouldn’t be viable without it.

“The insurance market reforms cannot function as Congress intended without the mandate and therefore should be struck down if the mandate is held to be unconstitutional,” the insurance trade group argued in a brief filed with the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association.

The old risk management strategy of medical underwriting—pricing premiums based on the underlying health risks of an individual or members of a small group—was no longer an option.

Community pricing would reduce premiums for people with pre-existing conditions or other health risks. But premiums would increase for younger and healthier people. Some observers feared that younger people might stay out of the market, then buy health insurance only when they became ill.

If that happened, it would throw off the risk predictions insurers had made, leaving them with an older, sicker population to cover. In the insurance business, this situation is known as adverse selection.

Timothy Jost of Washington and Lee University School of Law, in a 2010 report for The Commonwealth Fund, called that possibility “the greatest threat facing exchanges.”

Michael F. Cannon, a health policy expert at the Cato Institute, in 2010 saw the potential for an “adverse-selection death spiral.”

Risk Mitigation

The Affordable Care Act acknowledged the increased risk for insurers and included three provisions to keep premium prices stable.

First, the law included a risk adjustment. This was meant to protect health plans that wound up ensuring an exceptionally high-risk group of people. Plans that wound up with a lower-than-average risk group would make a payment to plans having a higher-than-average risk group.

Second, the law included a reinsurance program. This was to help plans deal with unexpectedly high medical costs for an individual enrollee. All insurers paid into a reinsurance pool. At the end of the year, each could submit a claim for individual enrollee costs that exceeded a certain threshold. This program, which was intended to be temporary, ran from 2014 through 2016.

Third, the law created risk corridors. This was to help health plans whose total claim payments exceeded the predicted amount. Plans that had lower-than-expected claim totals would pay into a fund. The fund would make payments to plans with claim costs higher than their target amount. This program was also intended to be temporary and ran from 2014 through 2016.

A customer meets with a Sunshine Life and Health Advisors agent while waiting for the Affordable Care Act website to come back online to purchase a health insurance plan in Miami on March 31, 2014. Joe Raedle/Getty Images

The Spiral Begins

The first several years of Obamacare saw lower-than-expected enrollment, higher-than-anticipated costs, and diminishing choice in the marketplace.

Enrollment was significantly lower than expected in the early years, which observers had warned could be a sign of adverse selection.

After a shaky start due to glitches in the online marketplaces, enrollment in 2014 actually exceeded the modest Congressional Budget Office forecast.

Yet the overall market grew by just 4.2 million that year, as many of the 8 million Obamacare enrollees were people who had moved over from the commercial market, according to a report by Amanda E. Kowalski of Yale University.

By 2018, Obamacare enrollment stood at 11.8 million, nearly 1 million less than in 2016 and less than half of the 25 million predicted by that date.

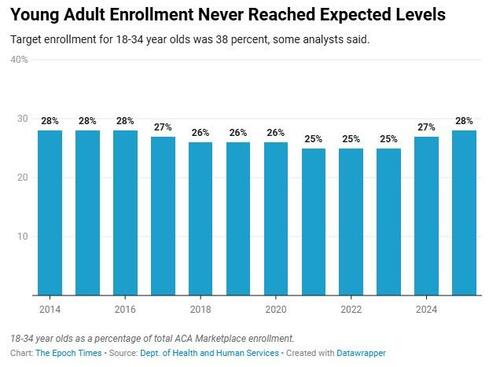

Data suggest that many of the missing enrollees were young adults.

Obamacare needed an enrollment mix that included 38 percent young adults to avoid a “death spiral,” Cato Institute reported in early 2014.

At the close of its first enrollment period in 2014, Obamacare had an enrollment pool that was just 28 percent young adults aged 18–34. A Commonwealth Fund report indicated that people whose premiums increased had been slightly less likely to buy insurance in 2014. Young adults would have been among those whose rates went up.

The individual mandate, which aimed to offset this factor, faced court challenges beginning in 2010. Though it was not ultimately ruled unconstitutional, Congress set the penalty for noncompliance at $0 in 2017, effectively ending the federal mandate.

A pedestrian walks past an insurance agency that offers Affordable Care Act plans, in Miami on Jan. 28, 2021. Following the COVID-19 pandemic and enhanced subsidies approved by Congress in 2021, enrollment more than doubled, reaching a record 24.3 million in 2025. Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Enrollee age was not the only indicator of adverse enrollment, Kowalski reported. Her analysis of cost data concluded that marketplaces in at least 16 states experienced adverse enrollment in 2014.

Data indicate the cost of insuring Obamacare enrollees exceeded expected levels in the early years.

The reinsurance program had obligations exceeding income by nearly $10 billion over three years.

The risk corridors program fared no better. Income was insufficient to meet obligations in 2014, so all 2015 income and at least a part of 2016 income was used to pay off the 2014 shortfall.

The increased coverage requirements had the predictable effect of increasing premium prices, according to a 2017 report by the Department of Health and Human Services.

“In most states these regulations increased insurance coverage requirements and would be expected, on average, to increase the price of [Affordable Care Act]-compliant plans relative to pre-[Affordable Care Act] plans all else equal.”

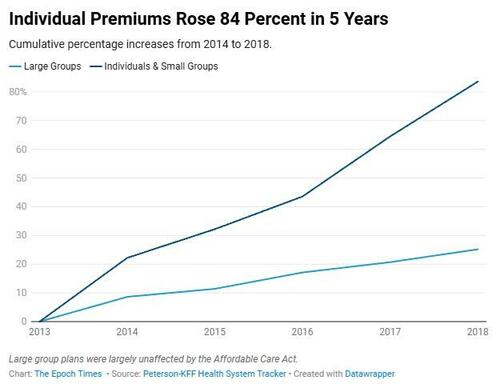

Premiums increased 22 percent in the first year and a total of 84 percent by 2018.

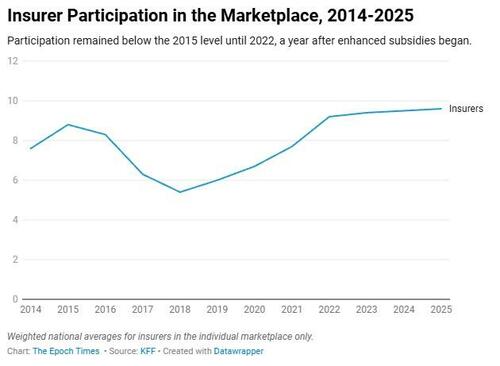

Insurers began to leave the marketplace. In 2015, an average of 8.8 insurers in each state participated in Obamacare, according to KFF. By 2018, that number had dropped more than one-third.

The COVID Years and Beyond

In the middle years of Obamacare, enrollment decreased, then plateaued after reaching a high of 12.7 million in 2016. Premiums decreased somewhat too, dropping about 9 percent over four years from their high point in 2018. And insurer participation ticked up slightly in 2019.

Then came COVID-19 and the enhanced premium subsidies created by Congress in 2021.

A woman wearing a face mask walks past a COVID-19 test site in Manhattan, N.Y., on Nov. 2, 2020. Chung I Ho/The Epoch Times

Those enhanced subsidies, which expired in 2025, provided financial help to Americans with higher incomes and further lowered the cost of Obamacare for low-income people. Enrollment more than doubled, reaching an all-time high of 24.3 million in 2025.

Yet as enrollment spiraled upward, so did premiums. Prices reached a new high in 2025, averaging $497 per month for a 40-year-old enrolled in the most popular plan.

What didn’t change dramatically was the age profile of enrollees. Though some young adults entered the market in the era of enhanced subsidies, their numbers never exceeded the 2014 rate of 28 percent.

And despite a rise in the number of insurers doing business in Obamacare, some of the largest companies say they find it unprofitable.

David Joyner, the CEO of CVS Health, testifying before Congress on Jan. 22, said its costs exceeded income in the Obamacare marketplaces last year, and Gail Boudreaux, CEO of Elevance Health—the parent company of Anthem—said it did not turn a profit from Obamacare in 2025.

David Cordani of The Cigna Group said, “We lost money in the exchange all but two years since 2014.”

Tyler Durden

Tue, 02/03/2026 – 17:40ZeroHedge NewsRead More

R1

R1

T1

T1