Much time has now passed since the re-election of the Albanese Labor Government in May.

While political analysts have rightly focused on Labor’s strong swings across the country and the abject collapse of the Liberal Party’s electoral footprint, less attention has been paid to the deeper crisis unfolding on Australia’s political right.

Despite widespread disaffection with the major parties, the right once again failed to convert a significant bloc of support into coordinated electoral gains.

The Liberals, having abandoned any serious invocation of Australian identity as a campaign anchor, find themselves at an existential crossroads: will they embrace Sussan Ley’s vision of a “modern Australia,” or return to their traditional conservative roots?

Meanwhile, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation—though gaining three-quarters of Labor’s swing and two senate seats—remains stalled in both structure and ambition, suggesting that its long-standing dominance over the populist right may now be under challenge.

In this fractured landscape, new forces are rising, and none more intriguing than Gerard Rennick’s People First, buoyed by strong support among election day voters and a distinctly different base to that of One Nation.

One Nation: Success or Stagnation?

The 2025 election has once again highlighted the remarkable ineptitude of Australia’s electoral right. Collectively, parties notionally to the right of the Liberal National coalition obtained close to a full quota in all states, yet this only translated to the election of One Nation senators in QLD, NSW and WA.

Clearly, a growing proportion of the Australian electorate is looking for political options beyond those offered by the major parties, yet to date this has not been capitalised on. The Australian Greens, by comparison, have successfully concentrated the left-wing vote to consistently elect multiple senators in every election since 2001.

Voters were given copious levels of choice among the right-wing parties, from the personality parties of Pauline Hanson’s One Nation and Clive Palmer’s Trumpet of Patriots, to the ideologically purist parties like the Libertarians, the ‘Christian’ politics of Family First and the Australian Christians, and the fringe minors of the Great Australian and HEART Parties. Australia’s right-wing scene continues to remain splintered.

The below graph shows the relative support for the most popular of these parties across the six states, highlighting the strong showing of One Nation and other right-wing parties:

One Nation dominated the right-wing vote across the nation, beating other right-wing parties in every state. Nationwide, they received a 1.4% swing towards them, three quarters of that achieved by the popular Labor government. The party returned three senators for the first time since the double dissolution election of 2016.

A result like this should represent a strong victory for the party, cementing its legitimacy in the Australian right-wing sphere and providing a strong mandate from conservative voters. Why then did the party have at best a muted celebration of such a colossal victory?

By contrast the election of three Greens members from Brisbane to the House of Representatives in 2022 saw the word ‘Green’ being attached to the entirety of the Oxford English Dictionary, whilst members begun preparations for the unending reign of Chairman Bandt.

The comparison with the Australian Greens is one which is not made frequently enough. This year represents the 28th year of operation for One Nation, contesting a total of 10 Federal elections. One might expect their vote share to grow – such is the evidence from comparable populist parties across the West. Yet despite this, One Nation have achieved 100,000 fewer votes this year than their debut at Federal elections in 1998.

That is a remarkable level of stagnation, especially when compared with the Australian Greens who achieved a 1.66 million vote increase across the same period. It is perhaps with this context that One Nation’s response to their successful election result makes some sense. Clearly the party of Australia’s ‘fringe’ is not only failing to repeat the success of the European right but is being outdone by their leftist counterparts. Severely.

One Nation’s biggest post-election announcement was that they were looking to open branches. Take that in for a moment – a party of 28 years is only now looking for the input of their members. This represents a significant response to a long-term criticism of One Nation from their right-wing base.

So why make this announcement now, after what was their most successful election in recent history? Long have One Nation been the preeminent right-wing party of Australian politics, yet despite their success this year, in every mainland state, except NSW, the collective right-wing minor party vote share outpolled One Nation (and in NSW the difference was just 0.02%).

Clearly right-wing voters are unhappy with One Nation as a party to represent their interests. Whether this push for branch membership represents a turning point for One Nation remains to be seen, but I am sceptical. After all, when two thirds of your elected representatives leave the party before their term expires, the prospect of the party outliving Pauline Hanson are slim.

So, who stands to gain? Much was spoken of the potential of the Libertarians coming into the 2025 election, even at The National Observer. Yet they failed to reach even 1% of the vote in most mainland states, with the sole exception being the commendable performance of Craig Kelly and the NSW Libertarians. Evidently, libertarianism is not an attractive prospect to the electorate.

The Australian Christians performed well in WA, continuing their presence in state politics in the West, but were at best a minor player on their NSW ticket.

By far the strongest challenge to One Nation came from Gerard Rennick, the former Liberal National Party senator, with his newly established People First Party in Queensland.

Despite minimal media coverage and a modest campaign budget, Rennick managed to gain almost 5% of the vote in One Nation’s strongest state. Here we take a closer look at the results from the Queensland senate election and the success of People First.

The Rise of People First:

Gerard Rennick’s People First party has quickly established itself as a serious contender in Queensland politics, drawing support from both traditionally One Nation and Liberal National Party voters, turned off by the Liberal Party’s vacillation and One Nation’s stagnation.

Despite operating with a skeletal mainstream media presence, People First outperformed both the Trumpet of Patriots (3.6%), and the Libertarians (0.5%), while narrowing the gap with One Nation (7.1%) to just over two percentage points.

An analysis of vote share by vote type provides further insight into the contrast between One Nation and People First.

In Queensland, Rennick’s support came disproportionately from ordinary election day votes, a traditional indicator of strong grassroots engagement. By contrast, One Nation’s strongest margins came not from election day, but from pre-poll ballots, which reflects a legacy recognition among disengaged and habitual protest voters rather than active enthusiasm.

The divergence suggests that People First was building electoral support up until election day, while One Nation increasingly relied on residual brand familiarity and passive voter identification, particularly as they are a mainstay of Queensland politics.

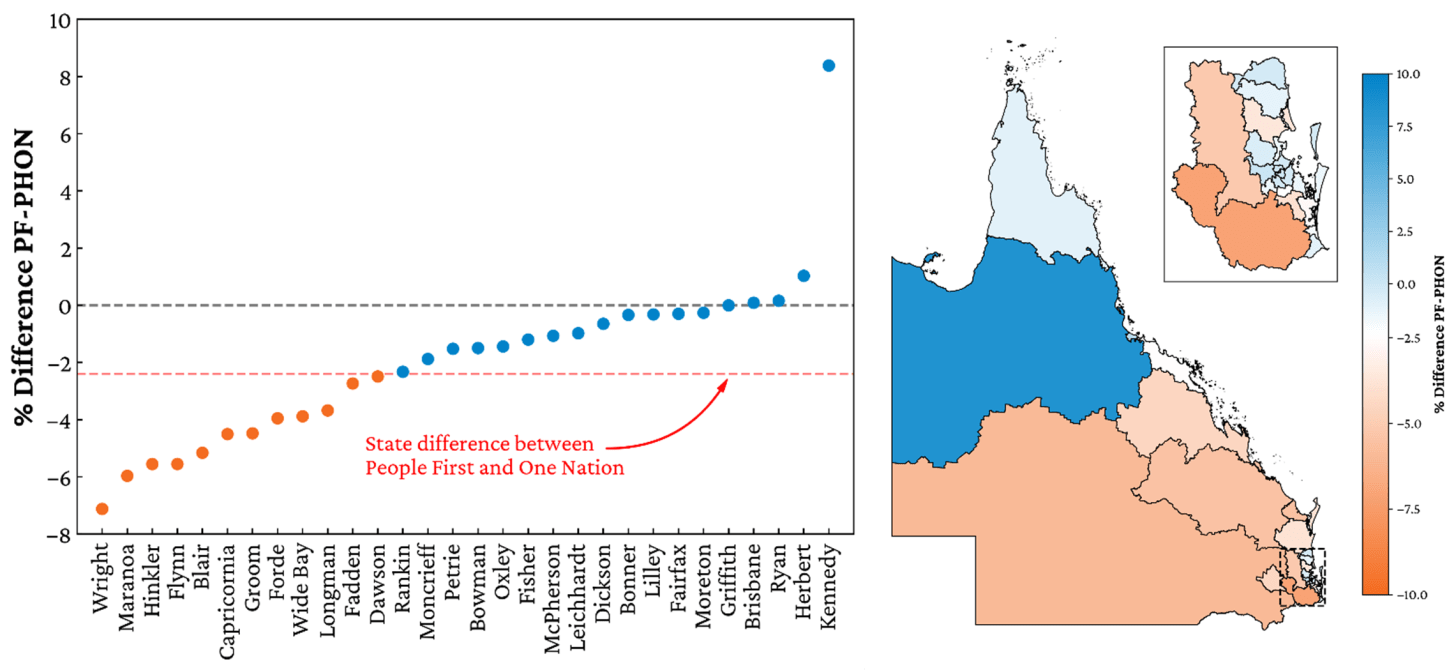

The below chart illustrates this divide, showing People First as the only right-wing party which had ordinary election day ballots as their strongest vote type.

In the southeast Queensland electorates – Brisbane, Ryan, Griffith, and the Sunshine and Gold Coasts – the picture is even more striking.

In many of these booths, People First beat One Nation outright, achieving strong results in the western booths of Ryan and Brisbane and the southeastern booths in Griffith.

In each instance the One Nation result remained similar to their 2022 result, even with People First entering the field – suggesting that Gerard Rennick is attracting a demographic of votes not serviced by the politics of One Nation. These electorates are among the most advantaged in the whole of Queensland, indicating that Rennick has an appeal to a different proportion of the voting public across Queensland.

Likewise, the endorsement of Bob Katter generated strong support for People First in the Northern Queensland electorates of Kennedy, Herbert and Leichhardt that have evaded One Nation’s grasp.

For a detailed look at the booth by booth results for People First and One Nation across Queensland and the corresponding demographics, see our interactive map of the election results available HERE ←

Who is voting for People First?

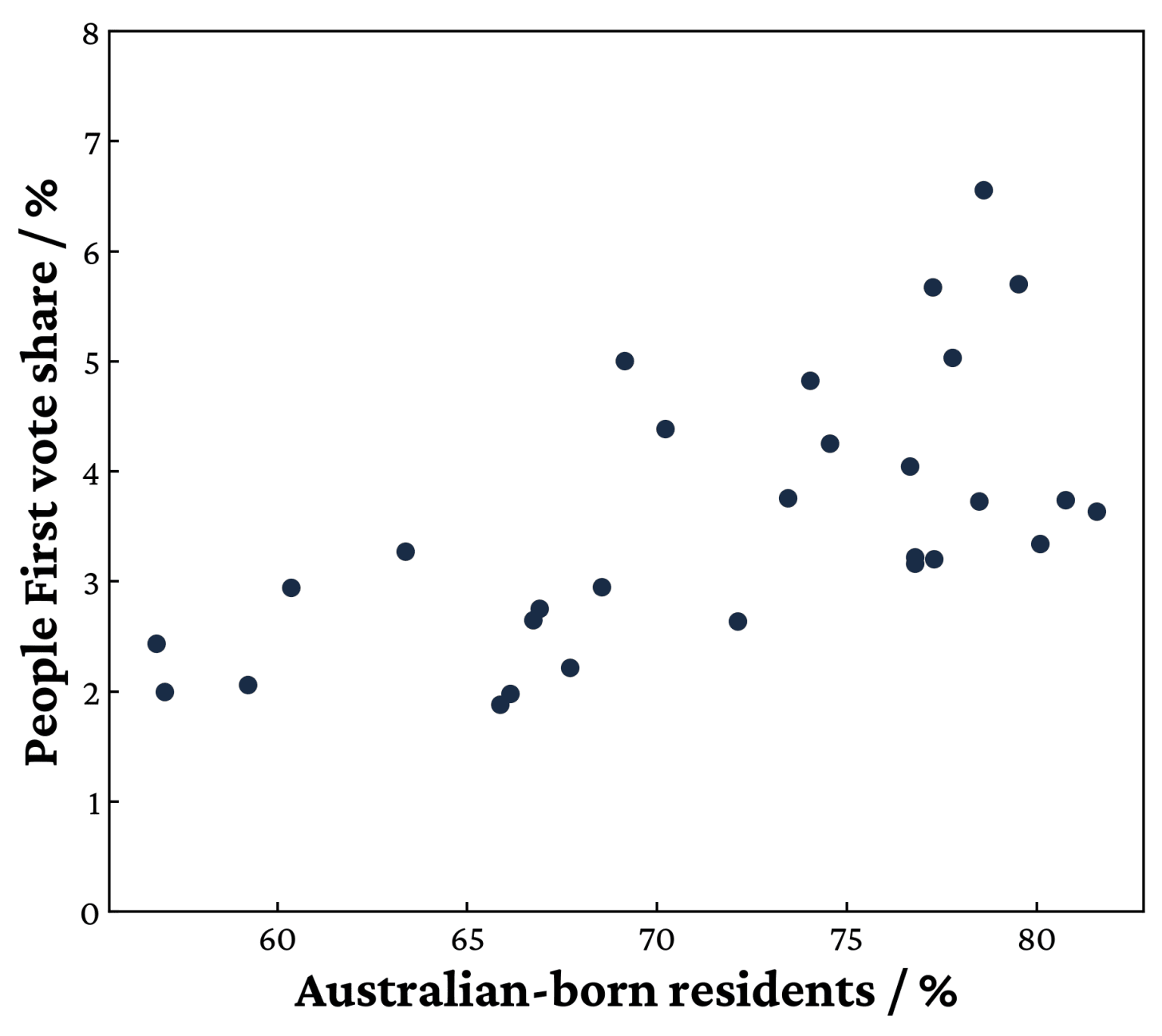

Using demographic data from the 2021 Census, the result from each Commonwealth electorate can be directly compared to the demographics of the region. This leads to some important insights about the types of voters choosing People First over One Nation, and where the party may target to improve their vote share in 2028.

Unsurprisingly, electorates with larger proportions of Australian born residents favoured People First. Electorates with over 80% Australian born residents had a People First vote share more than two times higher than electorates with an Australian born population below 60%. This was also true of the One Nation vote.

The largest differences between the demographic of the One Nation and People First voters appears by looking at electorate differences by area and tertiary education (for a further breakdown, the booth by booth data can be viewed via the interactive map HERE).

Most One Nation support comes from rural and regional electorates with low levels of tertiary education, with its strongest performances in the mining regions of Hinkler and Flynn and the agricultural districts of Maranoa and Wright. People First significantly underperforms One Nation in these electorates; however, they have equalled or outpolled One Nation in city electorates with higher levels of tertiary education.

These results are telling. While One Nation’s base remains firmly regional and aging, People First appears to be building a coalition among younger families and suburban workers, precisely the demographic the Liberal Party has haemorrhaged support from since 2019.

This mirrors the broader post-2016 realignment across the West, albeit to a lesser extent. Nationalist parties have been gaining traction among working- and middle-class voters disillusioned with major centre-right politics, exemplified in no better fashion than by the rise of Alternative for Germany (AfD) to the largest opposition party in the German Bundestag.

Perhaps most significantly, People First is cutting through in areas with higher levels of tertiary education, especially among socially conservative and younger nationalist voters – this can be seen in Rennick’s performance in the South-East of Queensland.

These voters are drawn to Rennick’s combination of calm, technocratic critique and traditionalist, conservative values which are a distinct contrast to the right-wing populism of Australia’s history; notably Hanson’s bombast and Palmer’s bluster which is broadly seen as both unpalatable and insincere, especially within more educated and wealthier segments of the Queensland public.

Where Hanson complains, Rennick reasons. It’s a different presentation, less about populist rage, more targeted towards genuine institutional insurgency backed by a self-consistent ideology grounded in Australian interest.

It is this key difference that presents People First as a more credible alternative to the other offerings of Australia’s populist right.

Across the globe, successful nationalist parties have brought more substance than simply anti-establishment rage, rather they position themselves as defenders of sovereignty and identity in a professional way.

This quality has been key to nationalist success across Europe as seen with Germany’s AfD, Italy’s Brothers of Italy under Meloni, and the Sweden Democrats—parties that advocated for institutional nationalism to varying extents (and subsequent commitment). This distinction was highlighted in The National Observer’s discussion with AfD insider Jörg Sobolewski, which can be watched in full here.

Whilst Gerard Rennick has much left to prove about the endurance and ideology of his party, a sign of preliminary success will be whether he can both pivot away from the COVID criticisms which saw his initial split with the Liberals and if he can eschew the slogans of Advance Australia, in favour of the coherent Australia First ideology to which his commerce education lends.

Where to from here?

If One Nation marked the arrival of Australian populism in the late 1990s, People First may signal its disciplined successor—a party less defined by protest and more by purpose.

In a fractured conservative landscape, Rennick’s model offers a compelling template: values-driven, culturally grounded, and member based. By looking to attract a new demographic of voter – urban, tertiary-educated, and patriotic – People First challenges the idea that nationalism in Australia must be loud, erratic, or reactionary.

What remains to be seen is whether this momentum can be sustained. Electoral success in 2025 was a promising start, but consolidation requires party-building, institutional depth, and a coherent ideological vision.

If Rennick can achieve this – if he can turn a protest moment into a policy movement – People First may not only replace One Nation but reshape the future of the Australian right, offering a real option for young nationalists.

In a country devoid of serious right-wing politics, still searching for a nationalist alternative, People First is certainly a step in the right direction.

Written by Flynn Holman, find more of his content on X @Flynn_Holman_.

This article originally appeared on The National Observer and is republished by The Noticer with permission.

The post What does a Rennick voter look like? first appeared on The Noticer.

The Noticer

R1

R1

T1

T1