Continued from Part I.

The Barsaloi shop

After marrying Lketinga, Corinne started a business. She rented a two-room wooden building near the mission. The main room had shelves and a counter in the middle that would be perfect for a shop. The back room would be mostly for storage, and Corinne put a charcoal grill in there so she could cook and make tea.

Lketinga got a business license, and he was proud because this would be the first Samburu-owned store in town. The Samburu bought things from the Somali merchants but did not like or trust them. Corinne’s mother-in-law, “Mama,” worried that the Somalis would become dangerous if the new store damaged their livelihood.

Corinne approached wholesalers in Maralal, haggled down prices, and got some to deliver her orders by truck. She purchased scales so she could sell staples like sugar, rice, and maize meal by-the-pound. She filled her store with bread and fresh produce, which had never been available in Barsaloi because the Samburu were a pastoral people who herded livestock but did not farm. The store had treats like candy and soft drinks, and items like matches and soap. Toilet paper would become a popular product. Lketinga bought miraa in bulk to sell. A crowd waited outside before the store’s grand opening. Nine days later, every item was sold out. Even the Somalis came in to buy miraa.

Corinne made frequent trips to Maralal to restock, so her car needed lots of repairs. Father Guiliani agreed to fix her car, and in exchange, Corinne drove sick people to the hospital, and drove children to and from the mission’s school.

Pregnancy

Corinne found out she was pregnant, and her friend Sophia, an Italian expat, was pregnant, too. Their due dates were only a week apart. Corinne visited Sophia whenever she went to Maralal. Sophia’s lifestyle was posher than Corinne’s; she lived in a two-story home with electric lights and a refrigerator. The ladies complained about their partners. Corinne had been annoyed with Lketinga for leaving their home a mess, with chewed miraa stems and food all over the floor, attracting ants. Sophia complained that her Rastafarian boyfriend wouldn’t work and wanted only to spend her money on beer.

Jealousy

It was common for Masai men to be extremely jealous, to a point that they would abuse their wives emotionally and physically. When Lketinga started falsely accusing Corinne of having affairs, the Masai women she discussed it with told her, “All men are like that.”

Corinne was asked to drive a Masai teacher’s pregnant wife to the hospital. She arrived at the teacher’s house to find his wife alone, bent double on the floor, moaning in pain, surrounded by blood. The woman allowed Corrine to look under her skirt; her baby’s arm was hanging from her vagina and it was blue. The teacher had not allowed his wife to go to the doctor because of his jealousy. Corinne’s car broke down on the way to the hospital, and they were stranded on the road at night, with huge horseflies biting them. In excruciating pain, the teacher’s wife managed to pull her baby out herself, and it was dead.

“I have to keep wiping tears out of my eyes. This teacher has almost killed his wife through his jealousy! The man who translates the mass every Sunday in church, who can read and write. . . What would happen if I developed complications?”

An ambulance eventually brought the teacher’s wife to the hospital, and she survived. When Corinne finally made it home, Lketinga gave her the third degree, asking why she was so late and who she had been with. Lketinga’s jealousy got progressively worse. He accused her of having affairs with schoolboys, the priests, and the men she did business with.

Relapses and minding the store

Because Corinne did not get proper treatment when she first came down with malaria, it became a chronic illness and she would have many relapses. She had to spend ten days in the mission hospital when she was five months pregnant. Lketinga minded the store while she was gone, and he allowed people to buy things on credit. Corinne had firmly told him, “No credit,” before they opened. She had paid for all of their stock with her dwindling savings. Lketinga thought “a Samburu shop” should help his people.

Fatigued, Corinne moved them from the manyatta into the back room of the store. She bought a proper bed, a table and chairs. Masai rules of hospitality interfered with this setup. As many as three warriors might suddenly be spending the night on their bedroom floor. They would show up asking for food, and they would leave gnawed bones on the floor. Corinne’s bed was stained with their body paint. She argued with Lketinga about it. Sometimes he sent the men to his mother, but other times he insisted they stay and be fed.

Corinne had a malaria relapse when she was in her eighth month. The fever and nausea came back and she would lose consciousness. Mama became convinced that someone put a curse on Corinne to kill the baby, and Corinne remembered coming to with eight Masai elders gathered around her, rubbing her stomach, singing and chanting.

Father Guiliani radioed for a plane to medevac Corinne to the mission hospital. She was delighted that her doctor was a Swiss woman. The malaria had caused such serious anemia that Corinne needed three blood transfusions. She was nervous about getting AIDS, but the doctor found a safe blood donation from Switzerland, and the white nurses volunteered to be donors.

The doctor and nurses advised Corinne to have the baby in Switzerland. If it were born in Kenya, the baby would be the property of Lketinga’s family and she wouldn’t be able to do anything without Lketinga’s permission. Now that she was married, Corinne couldn’t go to Europe without written permission from her husband. The doctor also told Corinne that she needed to gain weight or she could die from the blood loss involved in giving birth. Even the mission hospital, which was better than most in Kenya, did not have oxygen equipment, incubators, or pain medication.

Corinne didn’t think she could manage the long flight to Switzerland, so Sophia offered to cook for her to help her gain weight. Corinne rented a room near Sophia’s place. Lketinga wanted his mother to take care of Corinne. He showed up at Sophia’s house during dinner and made a scene, accusing Corinne of having an affair with one of Sophia’s friends.

Having a baby

By the time Sophia and Corinne checked into the maternity ward together, Corinne had reached her goal weight. The ladies were roommates in the hospital. Corinne had her baby first, a week early, but there were no complications. She named her healthy baby girl “Napirai.” The next day, Sophia also had a girl.

When Lketinga saw Napirai, he exclaimed, “She is looking like me!” The biracial child appeared more black than white. Lketinga was impatient for Corinne to return home, but she didn’t think she was strong enough to handle all of the housework and working in the shop, so she stayed in the hospital an extra week. After Sophia went home, her bed was filled by a black woman who was having her tenth child, and that woman died from anemia.

When Corinne went home, she had to hide her baby from everyone but close family because of a Masai superstition. They believed that people could kill a baby by wishing it dead. It was even considered bad luck to say the baby was beautiful. This was hard for Corinne; she longed to show off her baby, like she would have done in Switzerland.

Corinne and Lketinga were able to move out of the store’s back room and rent a house close by — one that had an indoor bathroom with an earth closet. The Masai veterinarian was a neighbor, and his wife became a good friend to Corinne. When she overheard Corinne and Lketinga arguing, she would come by later to check on Corinne. When Corinne’s malaria relapses left her bedridden, the vet’s wife cooked for her and washed Napirai’s cloth diapers. After more than two years in Africa, “This is the first friendship in which it’s not me, the mzungu, on the giving end, but a friend helping me without being asked.”

Corinne made enemies, too. Lketinga had hired a boy as a shop assistant, but he stole from the store and had to be fired. His father, a high-status Samburu, insisted that Lketinga owed his son five goats. Lketinga wasn’t strong enough to challenge the hierarchy and he wanted to pay, but Corinne got so angry that she grabbed the boy by the shirt, cursed at him in German, and spit at him. The boy’s father had to hold him back to keep him from hitting Corinne. Later, the boy came to Corinne’s door with a machete, saying he wanted to “settle things with the mzungu.” He arrived as Corinne was serving the police chief chai and the chief arrested the boy.

Quarantine

Corinne’s eyeballs turned yellow, and she was back in the hospital. This time she was diagnosed with hepatitis. Her liver was unable to process food, so she was put on an IV and her diet was limited to rice and potatoes. She and Napirai were quarantined in a hospital room for six weeks, and she felt like a prisoner. When Lketinga visited, he didn’t stay long. When word got out that there was a white woman in quarantine, strangers started coming to “visit,” but really just to stare at Corinne and her biracial baby through the glass wall. She tried to hide under her blanket.

Bringing Africa home

When her hepatitis quarantine was over, it was difficult for Corinne to maintain a healthy weight, and her doctor kept recommending that she recover in Switzerland. The doctor explained the problem to Lketinga, and he signed the permission documents for Corinne and Napirai to visit Corinne’s mother, although Corinne’s homeland was something Lketinga could scarcely imagine. He asked his wife, “Why you are always sick? Why you go with my baby so far? I don’t know, where is Switzerland.”

The first thing Corinne wanted to do when she got to Europe was to take a hot bath, but when she did, she got an itchy red rash. The Masai practiced scarification, decorating the body with patterns of scars, and Corinne had consented to get tiny cuts all over her skin. The hot water opened her wounds up and she started bleeding. A visit to the doctor revealed that both Corinne and her baby had scabies, mites burrowing under the skin.

Corinne stayed in Switzerland for two and a half weeks, long enough to celebrate Christmas and put on some weight. She landed back in Kenya on New Year’s Day 1990, and when Napirai saw all of the black faces again, she started crying.

Disco parties

A school was to be built in Barsaloi, and construction workers were housed in barracks. They had earnings to spend, but were stuck in the boonies, and Corinne realized she could make money by organizing a disco party. She ordered liquor, had a cassette player for music, and the back room of her shop became a dance floor. “The music’s playing, the meat is sizzling on the grill, and people are lined up outside the back door. Lketinga takes the entrance money . . . workers keep coming up and congratulating me on the idea.”

Mama babysat, so Corinne was able to join in the revelry. “For the first time in two years, I even dance myself and feel as if I’ve let my hair down.”

Bimonthly parties were more profitable than the store. When Lketinga’s younger brother James was on a break from school, Corinne hired him as a shop assistant. Lketinga saw that everyone in town was viewing Corinne as the boss and he resented it. His jealous fits became more frequent; he called Corinne a whore, in front of people. He even sabotaged the store by accusing male customers of having affairs with his wife, and banning them from shopping. Lketinga’s behavior and the primitive lifestyle started to wear Corinne down. “We argue more and more often, and it begins to occur to me that I don’t want to spend the rest of my life like this. . . . He stands there scowling at me or the customers; or else he’s off with the other warriors slaughtering a goat, and I come home to find the floor covered with blood and bones.”

Lketinga often insisted on driving the car, but he made stupid mistakes that led to costly repairs, and operating a car in the bush was expensive even when done right. Corinne was also financing Lketinga’s miraa and alcohol habits. Although her business was profitable, Corinne could never catch up financially. She had spent almost all of her savings from Switzerland. She finally started to fall out of love:

I feel that love slowly dying because of his lack of trust in me. I’m tired of perpetually having to rebuild that trust and at the same time bear the whole burden of making a living for us, while he hangs out with his friends. It makes me furious when men drop in, look at my little, eight-month-old daughter, and talk over potential marriage propositions with Lketinga, who listens to their proposals with interest. . . I am not going to sell her off to some old man as a second or third wife.

Corinne had seen many Masai weddings, and only the first wives looked happy. The third and fourth wives always married someone too old for them and had “misery written on their faces.” She also did not want her daughter’s future to include female circumcision.

Lketinga’s jealous rages got worse; he boxed Corinne’s ear and threatened to hit her with his rungu club. The drama made business fall off at the store, and eventually Lketinga would not allow Corinne to go to Maralal to restock. He insisted that she get by on goat’s milk and meat like all the other Samburu women. This had an impact on the whole town, and James announced that he was going to have to move away to look for work.

One last chance

Sophia moved to Mombasa to open a restaurant, and that inspired Corinne. She convinced Lketinga that they should start over by opening a souvenir shop on the coast, and that James could work in their new store. She hoped the move would save her marriage. She threw one last disco party in Barsaloi to raise money, and it was a great success. The Somali shopkeepers told her they admired what she achieved, and many villagers thanked Corinne for improving their lives.

Corinne found a shop to rent near the beach. To attract customers, she made fliers with a map to the store and drafted James and Lketinga to stand on the main road, handing them out to white tourists. She undercut the prices at the hotel gift shops, and customers found their way to her, especially the German-speakers. They were interested in hearing about her adventures.

Soon Corinne was able to hire another shop assistant and a babysitter. Once more, Corinne was a successful retailer, and Lketinga felt emasculated. He began to stay at the shop all day, possessively watching over Corinne, checking her handbag three times a day, following her to the bathroom, banishing her wholesalers, and being rude to customers. Corinne no longer enjoyed her work, and her friends started to avoid her because they couldn’t deal with Lketinga’s behavior either. When he said that another man must have fathered Napirai, Corrine booked the next flight to Zurich.

Escaping Africa

Corinne couldn’t leave Kenya without Lketinga’s permission, so she needed him to believe she and Napirai would be coming back. She told him that she wanted to take a break before the high tourist season started. She left her bank cards with Lketinga, and also had to leave behind her car and a fully stocked store. He gave her permission to leave for three weeks, but she stayed in Europe permanently.

Safe at her mother’s home, Corinne wrote Lketinga a goodbye letter, and she was much kinder than she needed to be.

“My world and yours are very different, but I thought that one day we could live together in the same world. . . . Find a new wife . . . a Samburu woman this time and not another white woman. We’re too different. One day you’ll have lots of children. . . I’m simply not strong enough anymore to continue living in Kenya. I always felt very alone there, had no friends, and you treated me like a criminal. You didn’t even know you were doing it . . . that’s just Africa. But I tell you once again: I never did anything wrong. . . . My family don’t think ill of you. They still like you but we are just too different.”

She also wrote to James, explaining, “I felt very alone there because I was white.” She told James that she had left her husband the car and the store’s inventory. “If he sells everything, he will be rich, but he’ll have to be careful or else your large family will simply use up all the money fast.”

In her goodbye letter to Father Guiliani, she told the priest, “My husband has a good heart, but there’s something wrong with his head. It’s hard for me to say that, but I’m not the only one who thinks so. All our friends abandoned us, and even some of the tourists were scared of him.” She asked him to help her get some money to her mother-in-law. Corinne felt guilty about bringing Napirai to Switzerland, while Mama was expecting that her granddaughter would help her get by in her old age.

Too different

When Corinne fell in love, she believed she could “become a proper Samburu wife.” The book is called The White Masai, but there is no such thing. Whether they loved her or hated her, Lketinga and his people always saw Corinne as a mzungu — an outsider, someone inherently different.” She often felt lonely. Except for the veterinarian’s wife, Corinne’s friends were all European expats; she naturally turned toward people of her own race.

Corinne badly wanted to fit in with the Masai, but she could not escape her own nature. She did not think like a Masai, and some aspects of their life were intolerable: female circumcision, child marriage, and bad health care. Corinne and Lketinga viewed things very differently. For example, she was proud of her store in Barsaloi because she thought it was something the town needed; she saw half-starving people and had to solve the problem by making Africa more like Europe. Lketinga thought the status quo was enough; his people had survived that way for generations.

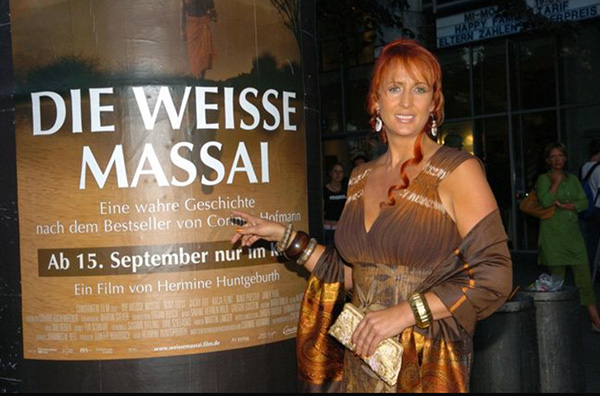

Corinne reared her daughter in Switzerland and this book made her rich. It was a best-seller in Europe and was made into a movie, Die Weisse Massai. It was translated into English, Spanish and Chinese. She wrote three more books: Back From Africa, Reunion in Barsaloi, and Africa, My Passion.

Corinne and the movie poster.

Despite the way he treated her, Corinne continued to give Lketinga and his family money. However, staying on good terms gave her material for her later books. She visited Barsaloi in 2004, but she did not bring Napirai because she was worried Kenyan law would require that the girl stay in Kenya. Everyone was happy to see Corinne again. Lketinga was married to a Samburu woman, and he fondly still thought of Corinne as his “first wife.” His brother James became a teacher. Corinne took Napirai back to Kenya as an adult to see her father.

Corrinne and Napirai.

Corinne eventually married a white European man. Her youthful foolishness led to a career as an author and expert on the Masai, but the real message of her story is that some groups are incompatible.

Corrine and her current husband.

The post The White Masai, Part II appeared first on American Renaissance.

American Renaissance

R1

R1

T1

T1